Smokey (the) Bear is still keeping his watchful eye on America's forests after 75 years on the job

The iconic advertising campaign originated as a way to protect the nation from its WWII enemies. Today, critics are asking if it's causing harm as well as good.

Smokey Bear turns 75 on Aug. 9.

The star of the longest-running public-service advertising campaign in U.S. history is now big on social media, with Facebook, Flickr, Instagram and Twitter accounts.

Americans are also still sending the imaginary character loads of real mail. The postal service has delivered hundreds of thousands of the bear’s many letters and occasional jars of honey to his own ZIP code: 20252.

Some 96% of Americans recognized this constant reminder to keep forests safe, according to a survey in 2013, making him about as familiar as Mickey Mouse and Santa Claus.

By the way, there’s no “the” in Smokey’s name. The word was added by songwriters to make their 1952 medley dedicated to the iconic image more catchy.

Wartime propaganda

I researched Smokey and six other public service ad campaigns for my book about the Ad Council, the nonprofit that creates public-service campaigns on behalf of clients like the U.S. Forest Service. It taught me that there’s much more going on with that friendly face than you probably realize.

The fire-prevention campaign, like the Ad Council itself, has a past rooted in wartime propaganda.

A Japanese submarine had surfaced off the coast of California on Feb. 23, 1942, and fired a volley of shells toward an oil field. This first wartime attack on the U.S. mainland caused little property damage and no loss of life, but it had an enormous psychological impact.

The threat to America’s national security including its vast lumber supply, needed to build ships and guns to fight the war, worried government officials and business leaders alike. The Forest Service worked with what was then known as the War Advertising Council, and later became the Ad Council, to create a fire prevention campaign.

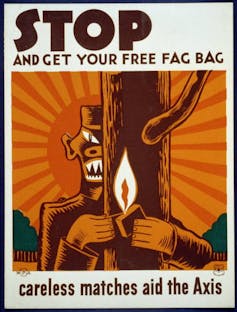

Some of the early posters harnessed the power of prejudice. One depicted a caricature of a Japanese soldier with a menacing grin as he held a lighted match against the backdrop of a forest, flanked by the slogan “Careless Matches Aid the Axis – Prevent Forest Fires!.” Another featured sinister renditions of Adolf Hitler and Japanese Prime Minister Hideki Tojo in front of a raging forest fire with the slogan, “Our Carelessness, Their Secret Weapon.”

With the war winding down in 1944, the Forest Service wanted the campaign to keep educating Americans about forest fire prevention, minus the scary imagery. After briefly featuring Bambi, the deer from the popular Walt Disney 1942 film, the Forest Service landed on a black bear. It hired New York artist Albert Staehle, who drew “Butch,” a floppy-eared cocker spaniel seen on Saturday Evening Post covers.

In 1944, Staehle created a tender-looking bear pouring a bucket of water over a campfire for the Forest Service. Three years later, came the well-known slogan that told Americans “only you can prevent forest fires.”

Whose land is it?

Sometimes, Smokey gets caught in the middle of the campaign’s roots in World War II patriotism, propaganda and racism.

Some scholars, including geographer Jake Kosek, who study anthropology and race even argue that the campaign is a symbol of white racist colonialism.

Kosek documented how the bear can trouble Native Americans, Chicanos and other people living off the land who are unhappy with the U.S. government’s land management policies.

In the forests of Northern New Mexico, local people see Smokey’s fire prevention message as a threat because they burn off small parts of the forest to plant crops or graze animals. Kosek found Smokey’s posters riddled with bullets in protest.

Kosek said the fire-suppression campaign reflects a belief, deeply rooted in the Forest Service’s history, that people who set fires in forests are deviants and evildoers.

A Smokey effect

There is also growing controversy about whether the campaign’s message contributes to the wildfire problem since research shows that some fires help forests.

To be sure, fire suppression as a policy didn’t originate with Smokey. It started after a disastrous fire in 1910.

In the 1930s there were 167,277 fires per year, according to a report from the Forest Service, other government agencies and the Ad Council. They credit Smokey for helping make that number fall to 106,306 in the 1990s. There may now be fewer fires, about 72,400 fires annually since 2000, but they have grown larger and more destructive in many regards.

Contrary to Smokey’s message, fires can be good for forests. There are forest management professionals who say the campaign interferes with the government’s ability to manage the problem by preventing small fires that clear out underbrush and tiny trees.

This is called “the Smokey Bear effect.”

The Forest Service itself said this phenomenon has made forests less healthy and increased the intensity of wildfires in some areas in its 2007 report, “Be Careful What You Wish For: The Legacy of Smokey Bear.”

Despite his critics, Smokey seems destined for an even longer career. That’s because the Insurance Information Institute says 90% of “wildland fires” in America are caused by people.

That could make Smokey’s message as important as ever.

Wendy Melillo does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Last nuclear weapons limits expired – pushing world toward new arms race

The expiration of the New START treaty has the US and Russia poised to increase the number of their…

Do animals have a future on Hollywood sets?

The turn to CGI has sidelined many of the dogs, bears and horses of yesteryear. But ethical questions…

Florida’s immigrant entrepreneurs are creating jobs and prosperity in their communities

Stories of Florida’s immigrant entrepreneurs show how immigrants find opportunities and fill economic…