How 'America's Got Talent' contestant Kodi Lee shattered stereotypes about disability

Lee, who is blind and autistic, upended the assumption, held by many, that people with disabilities lack rich interior lives.

If you haven’t seen Kodi Lee’s May 28 performance on “America’s Got Talent,” it’s worth a watch.

The 22-year-old Lee is blind and has autism. His rendition of Leon Russell’s “A Song for You” brought the crowd to its feet – and thrilled viewers at home.

“Loved this moment so much! Stood up and cheered in my living room!” Oprah tweeted.

Much of the media coverage portrayed Lee as someone who, in developing his musical ability to such a high level, overcame all odds – a common though sometimes troublesome trope used to describe people with disabilities who achieve any measure of success.

Lee is certainly an exciting talent. But as someone who teaches a course on the intersection of disability and music, I was moved by other aspects of Lee’s performance as well.

One challenge for people with disabilities can be that others tend to conflate their disability with their personality and identity. Their disability becomes the defining aspect of who they are, which can prevent people from realizing that those with disabilities can have rich interior lives.

So listening to Lee sing about love – mature, adult love – I heard a 22-year-old man whose voice and delivery brimmed with emotion and rang with authenticity.

“I’ve been so many places in my life and time,” he begins. “We’re alone now and I’m singing this song to you,” he croons, evoking deep intimacy and connection.

Infantilizing and de-sexualizing people with disabilities is still commonplace – as though physical or intellectual disability should necessarily exclude the ability to feel desire and the longing to be desired.

Lee shatters these notions. To sing these lines believably means to have lived them or to have imagined their truth.

Perhaps the most joyful aspect of Kodi Lee’s performance, however, is rooted in the dimension of time.

Philosopher and disability theorist Licia Carlson has written that “the experience of disability may be defined in negative terms when people fail to live according to what is considered to be normal time.”

In other words, because many tasks can take longer for someone with a disability, keeping pace can feel like a constant struggle.

This is where music can be such a beautifully transporting experience. It has its own time that’s not tied to that of the real world. With its tempo, rhythm and dramatic pacing, music creates its own temporal universe.

While listening to Lee perform, everyone in the audience was listening along at his speed, which, as the performer, he controlled.

It was a rare opportunity for disabled and non-disabled to be fully present together, under the same umbrella of time and space.

Finally, I think it’s important to return to the title of the show: “America’s Got Talent.”

After the Industrial Revolution, the ability to contribute labor and earn a paycheck became defining features of what it meant to be American.

If being a “true” American traditionally implied independence and autonomy, this one element of national identity alone could be enough to stigmatize people with disabilities.

Kodi Lee belted out an overwhelming assurance – as if it should have ever been needed – that a blind man with autism is also included in the definition of America.

Stan Link does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Trump says climate change doesn’t endanger public health – evidence shows it does, from extreme heat

Climate change is making people sicker and more vulnerable to disease. Erasing the federal endangerment…

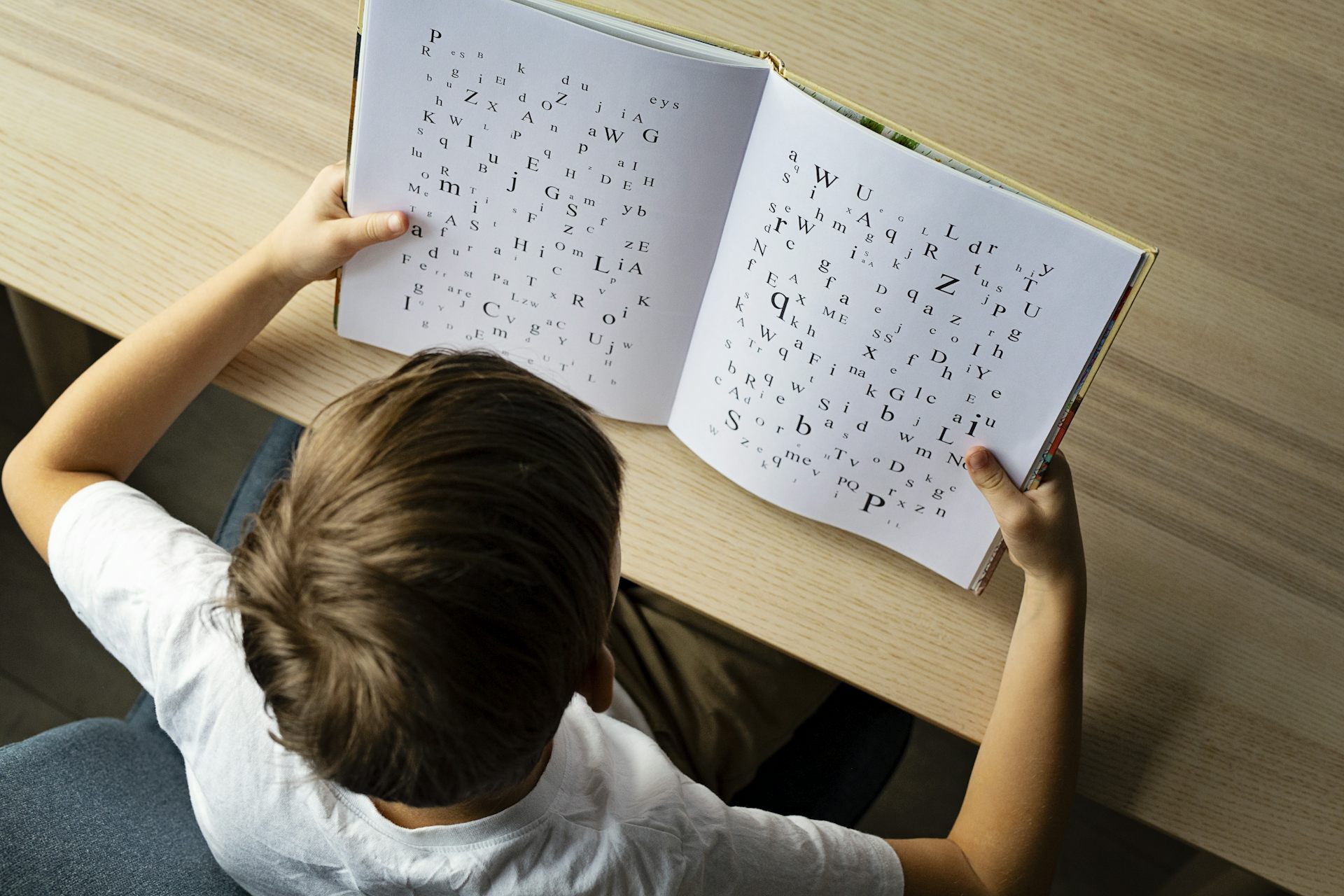

Nearly every state in the US has dyslexia laws – but our research shows limited change for strugglin

Dyslexia laws are now nearly universal across the US. But the data shows that passing a law is not the…

Citizenship voting requirement in SAVE America Act has no basis in the Constitution – and ignores pr

The House has passed a bill to require proof of citizenship for voting. Although it likely won’t become…