A quest to reconstruct Baltimore's American Indian 'reservation'

With her childhood neighborhood undergoing redevelopment, displacement and gentrification, a folklorist is working to preserve the history of a unique, urban community of Lumbee Indians.

A few years ago, I invited a group of students to go on a short walking tour of the Lumbee Indian community of East Baltimore.

Lumbee are indigenous to North Carolina but have been present in Baltimore since at least as early as the 1930s. My grandparents moved here in 1963 with their three children, one of whom was my mother. I was born here, and that makes me a first-generation Baltimore Lumbee. I grew up to be a community-based visual artist and a folklorist. I’m currently a doctoral candidate at University of Maryland College Park, where I’m finishing my dissertation on the changing relationship of Lumbee people to the neighborhood in Baltimore where they settled.

I had given such tours informally many times before, and had developed a familiar route and narrative along the way: South Broadway Baptist Church, the Baltimore American Indian Center, the Vera Shank Daycare and Native American Senior Citizens building.

This particular time, an elder of the community had come along with us. Naturally, I ceded the responsibility of leading the tour to her.

We started out on my usual route, but, to my surprise, she stopped us just outside South Broadway Baptist Church to talk about an Indian jewelry store that used to be next door. This was news to me. I didn’t remember the store because it was gone before my time.

I started to wonder: How much more don’t I know about the places and spaces Lumbee people once had here?

Drawing on the memories of our elders, the annals of local newspapers and other archival materials, I am now mapping and reconstructing East Baltimore’s historic Lumbee Indian community.

With the neighborhood being redeveloped and the Lumbee population shifting, I see this as an urgent project of reclamation – of history, of space and of belonging.

The birth of Baltimore’s ‘reservation’

The Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina is the largest tribe east of the Mississippi River, and the ninth-largest in the United States.

Our homeland is in southeastern North Carolina, with members residing primarily in Robeson, Hoke, Cumberland and Scotland counties. We take our name from the Lumbee River that winds through tribal territory, which is mostly rural and otherwise characterized by pines, farmland and swamps.

Following World War II, thousands of Lumbee Indians migrated from North Carolina to Baltimore seeking jobs and a better quality of life. They settled on the east side of town, in an area that bridges the neighborhoods of Upper Fells Point and Washington Hill, 64 blocks mostly comprising brick row houses with marble steps.

To many Lumbee newcomers, the buildings all looked identical. It was a world apart from the farm houses, tobacco barns, fields and swamps of home.

In this urban landscape, Lumbee people stood out – neither looking like the Indians on TV, nor neatly fitting into any of the races or ethnicities already living in Baltimore.

Today, most Baltimoreans would be surprised to learn that the area was once so densely populated by Indians that it was known as “the reservation.” An anthropologist who did fieldwork in the community during its heyday wrote that it was “perhaps the single largest grouping of Indians from the same tribe in an American urban area.”

The Lumbee community has gradually spread out in years since, so my own generation never experienced “the reservation” as such. But even within our own lifetimes – and especially over the last 15 years – we’ve seen the Lumbee population in the city sharply decline. The majority of our people have moved out to Baltimore County and beyond. Others have returned to North Carolina.

The old neighborhood is now being rapidly redeveloped. Historic buildings have been retrofitted. New luxury apartments abound. With the closure and sale of the former Vera Shank Daycare and Native American Senior Citizens building, the sole real estate that the Baltimore Indian Center owns is the building it occupies. The remaining elders are now in their 70s and 80s.

I know that I have arrived at this work in a crucial moment.

The neighborhood as it once was

In order to learn more about the historic community, I went to the elders first.

I was completely floored by what I learned. I had known about the places I already mentioned, along with a couple of much-fabled bars. But they talked about other restaurants, shops, more churches, more bars, investment properties and even a dance hall that were all Lumbee community-owned or frequented.

Nearly all of the sites described to me by the elders have been repurposed several times since the 1950s, if not demolished and utterly wiped from the landscape. Entire city blocks have disappeared.

How, then, could I even begin to pinpoint where things used to be?

This question prompted a spree of digging and plundering through many local institutional archives in search of clues that would help me reconstruct “the reservation.”

At the downtown branch of the Enoch Pratt Free Library, I was able to leaf through many historic newspaper clippings about the community and the early endeavors of the Baltimore American Indian Center, founded in 1968 as the “American Indian Study Center.” I even held original copies of the American Indian Study Center’s first newsletters, mailed directly from the center to the library.

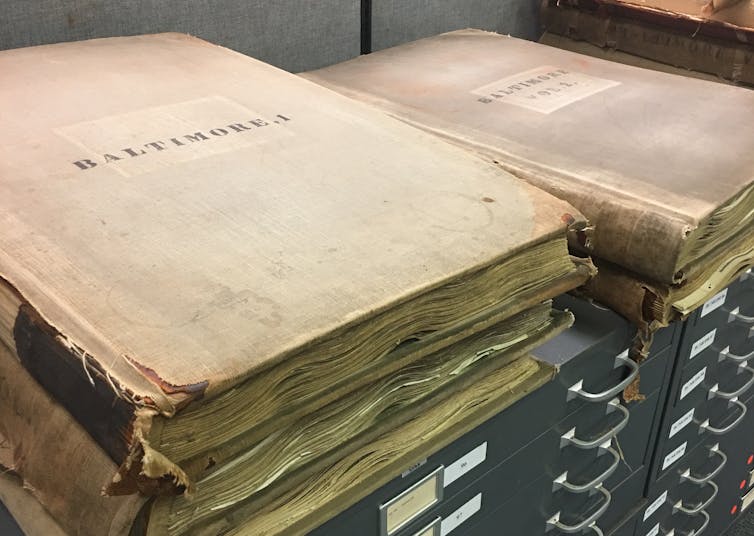

I got a cartography lesson at the Johns Hopkins University’s Eisenhower Library, which led me to visit the Baltimore City Archives, where I was able to handle original Sanborn maps. These maps provide extremely detailed aerial views of the neighborhood, including footprints of buildings that no longer exist.

Later, at the Baltimore City Department of Planning’s Commission for Historical and Architectural Preservation, I was thrilled to find actual street-level photographs of many of the buildings, which, ironically, were documented as a result of urban renewal.

In the Hornbake Library at University of Maryland College Park, I was able to consult several volumes of Polk Baltimore City Directories. I had presumed these were no more than old phone books. Instead, these volumes detail the individuals and businesses that occupied every building in Baltimore, street by street, block by block, in a given year. Not only was I able to confirm addresses of the community sites the elders had described, but in many instances, I was also able to see where they, themselves, had lived.

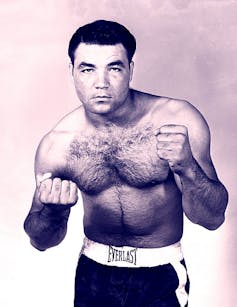

The Hornbake Library also houses the Baltimore News American photo archive, where I found portraits of community legends. There were Elizabeth Locklear, Herbert Locklear and Rosie Hunt – all founders of the Center. There was Clyde Oxendine, a boxer and the bouncer of the infamous Volcano, the meanest of mean Indian bars. And in the first folder of unprocessed photos I opened, I found, of all people, Alme Jones, the maternal grandmother of my fiance.

Preserving the past for future generations

So far, we have mapped 27 Lumbee-owned or frequented sites in and around the neighborhood.

After identifying materials from these many far-flung institutional archives, it seems imperative to establish a new collection so that these treasures can live together, alongside personal archival materials that would never have been accessible to an outside researcher. Our community needs easy access to its history.

Naturally, the Baltimore American Indian Center is the prime repository for this new collection. The Special Collections of the Albin O. Kuhn Library at UMBC is another. This amazing, publicly accessible resource already houses the Maryland Folklife Archives and the research of several Maryland folklorists. It will one day house my research as well.

Younger generations of Lumbee people should be able to see and know that our people’s history in Baltimore runs much deeper and wider than it seems.

All cities are steeped in stories. Whether we realize it or not, we are always walking in the footsteps of those who came before.

As Baltimore’s neighborhoods continue to change, its residents would do well to realize that Lumbee people have been here for a long time – and we’re still here.

Ashley Minner works for University of Maryland Baltimore County (UMBC) and is a doctoral candidate at University of Maryland College Park. She is affiliated with the Maryland Folklife Network and the Baltimore American Indian Center. She is an enrolled member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina.

Read These Next

Why Stephen Colbert is right about the ‘equal time’ rule, despite warnings from the FCC

The ‘equal time’ rule has been around for a century and aims to promote broadcasters’ editorial…

After a 32-hour shift in Pittsburgh, I realized EMTs should be napping on the job

A paramedic and university professor shares data about how strategic napping could help his own health…

Menstrual pads and tampons can contain toxic substances – here’s what to know about this emerging he

Heavy metals, phthalates and other potentially harmful chemicals have been detected in a range of menstrual…