The promise and peril of the Dominican baseball pipeline

Some of the best players in the world come from this small Caribbean nation, where an entire system of training young talent has blossomed. But few actually make it to the big leagues.

Latinos will comprise about 30 percent of Major League Baseball rosters on Opening Day, in large part because MLB has systematized its recruiting and developmental programs in the Caribbean over the last 25 years.

While researching my book “Raceball” in the Caribbean basin, I saw firsthand how this system operates: the way prospectors scour the Dominican Republic for the next nuggets of talent, the way players are selected and groomed at a young age, and the way a signing bonus in the thousands of dollars can transform an impoverished family’s life.

Few Dominican ballplayers, however, actually make it to the big leagues. Enmeshed in a system that encourages them to specialize in baseball at an early age, they’re left with little to fall back on when baseball doesn’t pan out.

The rise of the academy

When I first went to the Dominican Republic in 1984, scouting was rudimentary; a handful of scouts searched the countryside and “barrios” for prospects, observing young players and projecting how they might develop with better training and nutrition.

At the time, most youth played for amateur and semi-pro squads that represented communities, sugar mills, military units and banana plantations. The first generations of Dominican major leaguers – players like Felipe Alou, Juan Marichal and Manny Mota – came from these teams and signed for a few hundred dollars.

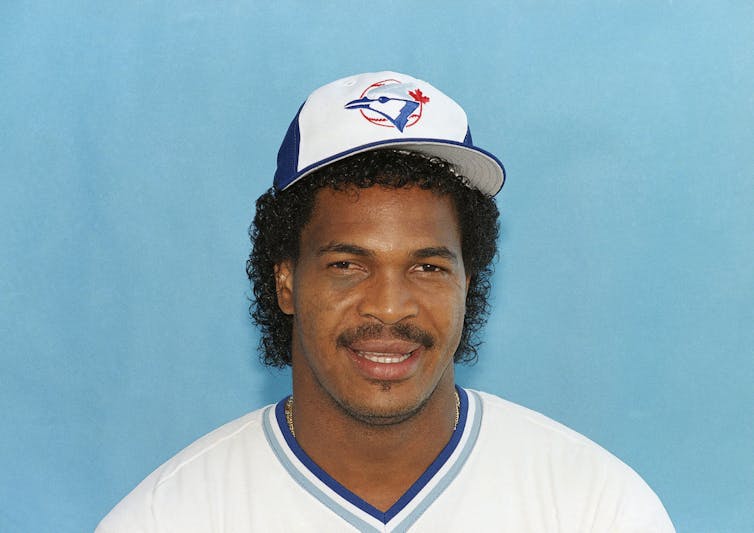

In the 1970s, Epy Guerrero, a former minor leaguer, opened the first academy devoted to grooming MLB talent, a spartan facility outside Santo Domingo. He later formed a partnership with the Toronto Blue Jays and developed stars like George Bell and Tony Fernández.

When I visited, Guerrero’s charges trained for hours under a scalding sun. But compared with their peers cutting sugar cane in adjoining fields, or the army of scavengers picking through mounds of trash at a nearby Santo Domingo dump, the work seemed plush. Baseball clearly offered an opportunity for a far better future.

By the mid-1980s, Latinos made up one-ninth of all major leaguers; half were from the Dominican Republic, then a nation of 6 million.

In 1987, the Los Angeles Dodgers took the academy model to a new level, opening Campo Las Palmas near San Pedro de Macorís, the sugar-cane milltown known as “the cradle of shortstops.” Las Palmas was a gated compound featuring well-manicured fields, dorms with hot water and top-notch coaches.

“There is nothing like it in all of the Caribbean,” Juan Marichal told me as we watched a game there in July 1987. It soon produced an astonishing number of stars, including Pedro Martínez, Adrián Beltré and Raúl Mondesí.

Signing bonuses balloon

The Dodgers’ success prompted each organization to eventually open an academy of its own, and these academies turned the 1980s wave of Dominican ballplayers into a tsunami of talent. Today, Dominicans alone now number more than one-tenth of all major leaguers.

In some ways, the academy system has been a win-win for Dominicans and Major League Baseball. In 1990, teams signed 281 boys, paying them a total of US$750,000 in bonus money. Most received $2,000 to $5,000, a small fortune for their families.

But by 2009, aggregate bonuses for foreign-born prospects had soared to $70,000,000, with most going to Dominicans. Several boys received payouts of more than a million dollars. In 2018, the Blue Jays doled out a $3.5 million signing bonus to Dominican shortstop Orevelis Martinez.

Latin youth benefit from two MLB policies. The first is that only players from the U.S., Puerto Rico and Canada are eligible for the annual player draft. So Dominicans – along with other foreign-born prospects – begin their careers as free agents and can sign with the club offering the best deal.

The second policy is that a boy cannot sign professionally until July of the year he turns 17. This means that top prospects can become millionaires as young as 16 but are off-limits when they are younger.

At the same time, a system devoted to identifying and training talented ballplayers in their early teen years – in exchange for getting a piece of the bonus money – has developed. Headhunters called “buscones” persuade families to let them train their sons, usually 13 to 16 years old, at their facilities. They house, feed and provide medical care for boys, who often leave school to focus on baseball. As boys near their 17th birthday, buscones take them to tryouts in the hopes of sparking a bidding war.

In return, buscones get 30 percent or more of the signing bonus money. Some are trustworthy advisers. But others will try to boost the appeal of their prospects by giving them performance-enhancing drugs – often cheap veterinary steroids – or altering their birth documents so they appear younger.

Once they’re signed, the prospects enter the academies run by Major League Baseball clubs. There, they’re given some instruction in English and life skills to prepare boys for the culture shock they confront if promoted to the U.S. Most boys, however, never leave the island, and many who do are released after a few years stateside. In the end – at most – 3 to 5 percent of Dominicans who sign reach the majors.

Little to fall back on

When cut, what do these Dominican boys have left to show for their monomaniacal commitment to baseball? Most never finished school and lack marketable skills. Some find low paying work in the game, but for many, their time in the academy was the high point of their lives.

The system rewards those who make it but quickly forgets those who don’t. In recent years, clubs have upgraded their educational programs and verbally committed themselves to investing in Dominican communities. Some clubs, like the Mets and Pirates, are more serious about these efforts than others, and some youth whose careers end at the academy are better prepared for the future as a result.

But that does nothing for the boys who have been training for years and never make it to an academy.

Alan Klein, an anthropologist at Northeastern University who has studied the academies since their inception, told me that MLB should focus “at the back end,” when players are “transitioning out of their career” rather than when they’re struggling to jump start one.

“Going to classes has rarely been valued in their young lives, and less so when they’re so hungry to escape their circumstances,” he said. “Teams should provide opportunities to get an education when they’re older, more appreciative, and can see the value of it – once they’re out of the commodity chain.”

That education should be “pragmatic – a hybrid between formal education and job-based skills,” he added.

Klein doubts that most teams, despite the hype over education, really care.

“They’re in the business of fabricating talent, and their interests are short term. It’s been that way for the past 25 years,” he said.

Given how much Major League Baseball has benefited from the labor of Latino players, surely it could do more. The league could start by funding a study to investigate what happens to those whose careers fizzle out before making it to an academy and find ways to invest in their lives and communities.

Those investments wouldn’t produce ballplayers or enhance clubs’ bottom lines. But it would pay back some of the social debt the league has incurred in the Caribbean.

Rob Ruck does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

The greatest risk of AI in higher education isn’t cheating – it’s the erosion of learning itself

Automating knowledge production and teaching weakens the ecosystem of students and scholars that sustains…

FDA’s abrupt flip-flop on Moderna’s mRNA flu shot highlights growing risks to drug-makers of investi

After pushback, the agency reversed course and agreed to review Moderna’s application after all.

I asked students whether they’d want to be teachers? They quickly responded, ‘Why would I?’

Approximately 52% of teachers in 2024 said they would not advise young adults to enter the profession.