The bias hiding in your library

The way books are sorted at the library can be highly political, touching upon issues of race and identity.

For many years, the Library of Congress categorized many of its books under a controversial subject heading: “Illegal aliens.”

But then, on March 22, 2016, the library made a momentous decision, announcing that it was canceling the subject heading “Illegal aliens” in favor of “Noncitizens” and “Unauthorized immigration.”

However, the decision was overturned a few months later, when the House of Representatives ordered the library to continue using the term “illegal alien.” They said they decided this in order to duplicate the language of federal laws written by Congress.

This was the first time Congress ever intervened over a Library of Congress subject heading change. Even though many librarians and the American Library Association opposed Congress’s decision, “Illegal aliens” remains the authorized subject heading today.

Cataloging and classification are critical to any library. Without them, finding materials would be impossible. However, there are biases that can result in patrons not getting the materials they need. I have worked in university libraries for over 20 years, and I’d like to highlight some issues of bias that you need to be aware of in order to find what you’re looking for.

How library catalogs work

The U.S. does not have an official national library. However, the Library of Congress fills this role on several fronts.

Many libraries across the U.S. adopt policies established by the Library of Congress, such as their call numbers and subjects for cataloging books. Its subject headings system is one of the most popular in the world.

Subjects are used to assign call numbers, so that items on similar topics are grouped together. An item will have only one call number, but it can have multiple subjects.

Using a specific system ensures consistency. For example, imagine how many variations of “William Shakespeare” you might have to search for if libraries did not use the authorized term “Shakespeare, William, 1564-1616.”

The ‘straight white American man’ assumption

In April 2018, I presented my research into issues of library bias in the Library of Congress Classification and Subject Headings at NCORE, the National Conference on Race and Ethnicity in Higher Education in New Orleans.

Today, when I search for subjects containing “women” or “men,” the results are unbalanced. There are 4,065 subject terms containing “women” and only 444 containing “men.”

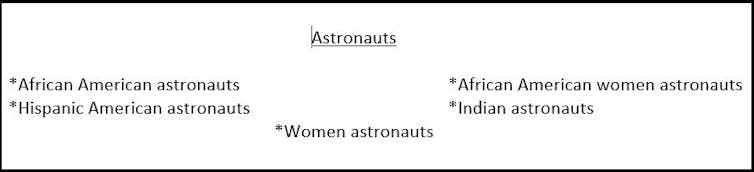

One example of bias is subjects containing the word “astronauts.”

Women are designated with “Women astronauts” and “African American women astronauts,” but there is no subject heading for male astronauts. A book about astronauts who are men would have the general subject “Astronauts,” unless the racial identity prompted the use of a subject like “Hispanic American astronauts” or “Indian astronauts.” Likewise, a book about Russian astronauts would have a geographic subdivision added: “Astronauts – Soviet Union” instead of “Russian astronauts.”

Without gender, race or geographic qualifications, “Astronauts” can be assumed to mean white American men in terms of library subjects.

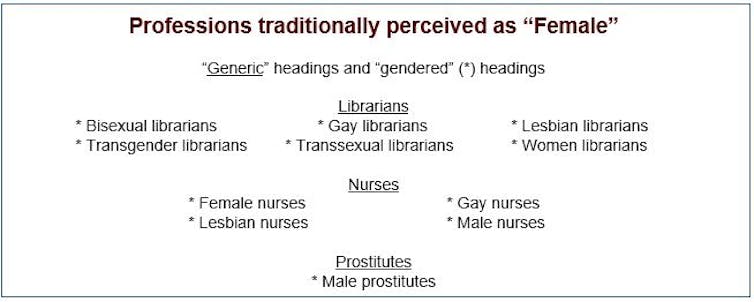

Another exercise I did was to search for professions that are traditionally perceived as female. Nurses, for example, were divided equitably, with subjects for both “Male nurses” and “Female nurses.” However, under “Prostitutes,” there was only a “Male prostitute” subject heading, revealing the generic assumption that most prostitutes are female.

This is not to say that there aren’t positive changes occurring. For example, in the late 1970s, “Afro-Americans” replaced “Negroes.” This was in turn replaced by “African Americans” or “Blacks” in 2000. In 2001, “People with mental disabilities” replaced “Mentally handicapped” and “Retarded persons.”

Gender identity is also an area where positive changes have been made. LGBT subjects have been distinguished and classed under “Sexual minorities” since 1972, rather than being under the subject “Sexual deviations,” as they previously were. “Sexual deviations” does not even exist as a subject heading anymore.

In December, the Library of Congress changed the broader term from “sexual minorities” to simply “persons,” in order to align with how other minorities are handled.

The classification dilemma

Many items cover multiple subjects, yet a single physical item can only be shelved in one location. Selecting a call number automatically devalues other subjects, but it must be done.

For example, take the book “Women of the Depression: Caste and Culture in San Antonio, 1929-1939.” Would you classify it under women’s history, Depression of 1929, Texas history or somewhere else?

Catalogers rely upon publisher-assigned subjects and summaries to help assign library subjects. These subjects, the Book Industry Standards and Communications codes, consist of 52 main categories, which are not as specific as Library of Congress subject headings. This can result in incorrect subjects being applied.

For example, I recently cataloged a book about basketball. The BISAC subject was “sports.” While it’s true that basketball is a sport, if I assigned “sports” as the main subject, it would be classed somewhere around GV704, but if I assigned the subject “basketball” it would be classed under GV885. Between these numbers, there could be books covering rules, the Olympics, equipment, air sports, water sports, winter sports and roller skating before the “Ball sports” starting with baseball. This difference could result in the patron not finding the book if browsing the shelves where the other basketball books are.

So the issue is that, by prioritizing certain subjects over one another, it might be more difficult for readers to find what they’re looking for. Women’s history books (HQ1121) may be far away from books about the Depression of 1929 (HB3713); therefore, someone looking for books about the Great Depression might not find the book she needed if it was classed in women’s history.

In my experience, catalogers try to be unbiased when applying subject headings and call numbers. But established subjects are created and adapted based on societal norms. If you can’t find what you need in your library, be aware that the term you use today might not be the term that was previously created. Ask your librarian for help.

Amanda Ros is an active member of the American Library Association.

Read These Next

As war in Ukraine enters a 5th year, will the ‘Putin consensus’ among Russians hold?

Polling in Russia suggests strong support for President Vladimir Putin. Yet below the surface, popular…

Trump administration axed nutrition education program that saved more money than it cost, even as go

Every dollar spent on community health education through SNAP-ED saved an estimated $10.64 in Medicaid…

Why the ‘Streets of Minneapolis’ have echoed with public support – unlike the campus of Kent State i

In 1970, National Guard troops killed four protesters at Kent State University. In 2026, federal agents…