New AI art has artists, collaborators wondering: Who gets the credit?

Because a host of artists and programmers can leave their stamp on a final product, disagreements and claims of theft have ensued.

Over the past few years, many artists have started to use what’s called “neural network software” to create works of art.

Users input existing images into the software, which has been programmed to analyze them, learn a specific aesthetic and spit out new images that artists can curate. By manipulating the inputs and parameters of these models, artists can produce a range of interesting and evocative images.

This work has gained widespread recognition through gallery shows, media coverage and two high-profile art auctions.

As an academic researcher, developer of artistic technology and amateur artist, seeing artists embrace new technology to create new forms of expression always thrills me.

But, like previous groundbreaking art movements, neural network art raises difficult questions: How do we think of authorship and ownership when these artworks come from the contributions of so many different creative individuals and algorithms? How do we ensure that all the artists involved are treated fairly?

A movement is born

The vibrant neural network art world arose in the past few years, in part, from developments in computer science.

It began in 2015 with a program called DeepDream, which was developed accidentally by a Google engineer. He sought a way to visualize the workings of a neural network system designed to analyze images. To do this, he gave it an input photograph and asked it to increase the number of object parts detected in the image. The result was a panoply of weird and evocative images.

He shared his method online, and artists immediately began to experiment with it. The first gallery show of DeepDream art occurred less than a year later.

Because this software is all freely shared online, digital artists can experiment with these models, and then share their own results and modifications.

There’s an active creative community of neural network artists on Twitter who discuss the results of their experiments, along with the latest developments and controversies. And major mainstream artists have also embraced these tools, with major shows and commissions by artists like Trevor Paglen, Refik Anadol and Jason Salavon.

Nonetheless, this open sharing challenges the ways we think about art. Christie’s sale of the image “Edmond de Belamy, from La Famille de Belamy” in November 2018 for nearly US$500,000 indicated that something was awry.

Why? To make this image, the artist group Obvious used the source code and data that another artist, Robbie Barrat, had shared freely on the web.

Obvious had every right to use Barrat’s code and claim authorship of the work. Nonetheless, many criticized Christie’s for elevating the artists who played only a small part in the creation the work. This was generally read as a failure of Christie’s, particularly in the misleading way it promoted the work, rather than a need to rethink authorship of AI art.

The emergence of Ganbreeder

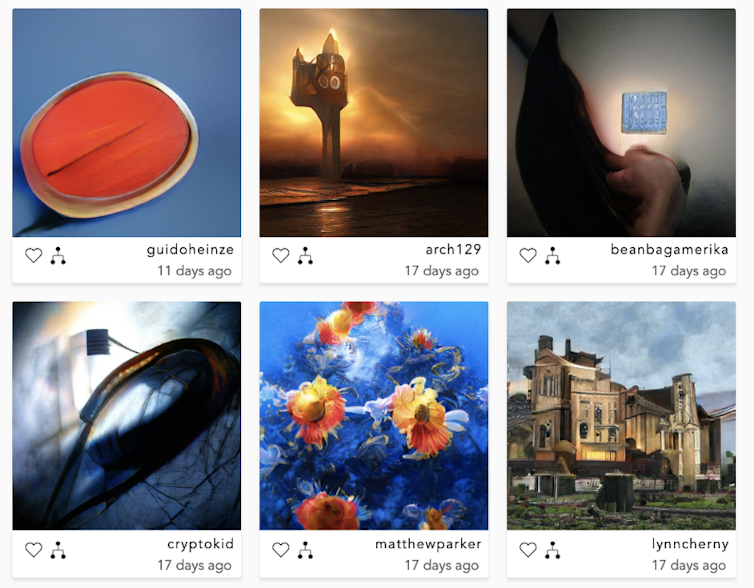

These issues really become unavoidable in Ganbreeder, a beguiling new website for creating images with neural networks.

Ganbreeder is an endless source of inspiring, intriguing, weird and fascinating imagery. Unlike the images that emerge from DeepDream, which quickly become repetitive, it seems like no single human mind could ever be capable of producing Ganbreeder’s diverse range of original imagery.

Ganbreeder was launched last November by Joel Simon. Each Ganbreeder image is created with input parameters that you choose by modifying the parameters of other images on the site. The site stores the lineage of each image, so that you can see all who contributed to a final image.

If you like an image you’ve found or created, you can order a custom print on wood from an entrepreneur and artist named Danielle Baskin. She touches up the print with paint, but instead of signing it, labels the back of the work with a QR code that points to image’s unique lineage.

She does this because each image is the result of many people’s contributions, which makes it difficult to attach the name of any one sole artist to each new artwork.

Giving credit where credit’s due

A sole artist, however, has already taken credit.

When Alexander Reben exhibited paintings he’d made of Ganbreeder images, Baskin accused him of stealing, since she and others had spent hours on the Ganbreeder site to make the images. To defend himself, Reben pointed out that Ganbreeder works were anonymous when he selected his images; user logins and attribution were only added in February.

Existing laws and conventions already address cases in which artwork is created in some form of collaboration or remix. It’s generally accepted that an artist can claim authorship simply by selecting a final image, though they should be upfront about the sources, when possible. The accusations of stealing seem to mimic those lobbed against conventional appropriation artists like Andy Warhol and Richard Prince, who famously enlarged and modified Instagram posts made by other users.

However these neural network works seem to be a different sort of work. The contributions of the neural network model and the other users of the site are all inseparable from the result. No one contributor seems to be “the artist.”

One possible way to view these new works of art is to think of them like open source software. Open source is a model for software development in which anyone can contribute to or use open software packages. It has led to the creation of major software tools, like Linux and major neural network software, that could not have been developed otherwise. Likewise, the new neural network artworks could not have been created without open sharing of software and data.

Open source projects specify clear rules for how the software may be used and credited: Some software may be extended and sold, while other projects must always be distributed for free. Each programmer’s contributions are recorded; how they are credited also depends on the individual project.

Like open source software, sites like Ganbreeder could establish clear rules for artistic authorship and credit. The guidelines should establish how to claim credit for a work, who else must be credited, and when a work can be sold or copyrighted.

Payment is a tricky issue. What happens when Ganbreeder images are used for commercial work – say, book covers or film production? For more mundane contributions, Baskin has suggested that payment could be shared among the work’s many contributors. This could become profitable; the royalties from a single major advertising campaign could pay for a lot of artists’ meals.

A ‘photography of imaginary things’

Then there’s the issue of value and intent. Can these works ever rise to the status of great art?

Some of an artwork’s value simply lies in its intrinsic aesthetic properties, the way a mountain might be beautiful. But we also value work because it emerged out an artist’s vision, intention and skill.

An open source artwork lies somewhere in the middle. This imagery represents the outcome of many human minds making deliberate artistic selections. But where was the intent? Surely, an early contributor had no idea how their work would be used.

Is it like asking for the intent behind a beautiful mountain? Or is the artist making the final choice the sole source of intent?

Previous art technology raised similar questions, notably with the invention of photography. When the medium first emerged, many claimed that photography could not be art at all. After all, they argued, it’s the machine that’s doing all the work – a sentiment now echoed in today’s misguided claims that “AI creates its own art.”

It took a while, but photography was eventually recognized as its own artistic medium. Moreover, it catalyzed the modern art movement by forcing artists to stop placing realism on a pedestal. Because they could never match the realism of the camera, they needed to figure out a way to create works that no mere machine could replicate.

Neural network art is now a kind of photography of imaginary things.

Like photography, neural art can create a seemingly infinite set of images, none of which seem to have much value on their own. The value comes from the unique way in which the artist uses these tools – how they set parameters, select subjects, adjust image details or curate a set of images that make a larger point.

With new neural models being released at a staggering pace, these issues will only become more urgent as more wonderful, weird and inspiring imagery emerges.

Aaron Hertzmann works for Adobe Research, however, opinions expressed here are solely his own.

Read These Next

Tiny recording backpacks reveal bats’ surprising hunting strategy

By listening in on their nightly hunts, scientists discovered that small, fringe-lipped bats are unexpectedly…

Bad Bunny says reggaeton is Puerto Rican, but it was born in Panama

Emerging from a swirl of sonic influences, reggaeton began as Panamanian protest music long before Puerto…

Will AI accelerate or undermine the way humans have always innovated?

An anthropologist’s new book lays out the formula for human innovation, from stone tools to supercomputers.…