How white became the color of suffrage

Being the media-savvy women that they were, suffragists realized they needed to come up with a meaningful, recognizable brand.

During President Donald Trump’s Feb. 5 State of the Union address, scores of Democratic congresswomen wore white to pay tribute to suffragists and their fight for women’s rights.

In the past, other politicians have done the same. Hillary Clinton wore a white pantsuit during her acceptance speech at the 2016 Democratic National Convention, and Congresswomen Shirley Chisholm and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez chose to wear white while being sworn into office.

As a historian who writes about fashion and politics, I like these types of sartorial gestures. They show the relevancy and power of fashion statements in our political system. These Democratic congresswomen, like the suffragists that came before them, are using their clothes to control their image and spark a conversation.

However, today’s strong association between the color white and the suffragists isn’t fully accurate. It’s based more on the black-and-white photographs that circulated in the media, which obscured two colors that were just as important to the suffragists.

Using color to convince

For most of the 19th century, suffragists didn’t incorporate visuals in their movement. It was only during the early 20th century that suffragists started to realize that, as Glenda Tinnin, one of the organizers of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, argued, “An idea that is driven home to the mind through the eye, produces a more striking and lasting impression than any that goes through the ear.”

Becoming aware of the way visuals could shift public opinion, suffragists began to incorporate media and publicity tactics into their campaign, using all kinds of spectacles to popularize their cause. Color played a crucial role in these efforts, especially during public demonstrations such as pageants and parades.

Part of their goal was to convey that they were not devilish Amazons set to destroy gender hierarchies, as some of their critics claimed. Rather, suffragists sought to present an image of themselves as beautiful and skilled women who would bring civility to politics and cleanse the system of corruption.

Suffragists deployed white to convey these messages, but they also turned to a much more diverse palette.

The 1913 Washington, D.C. parade was the first national event that put the cause of the suffragists on front pages of newspapers around the country. Organizers used an intricate color scheme to create an impression of harmony and order. Marchers were divided by professions, countries and states, and each group adopted a distinct color. Social workers wore dark blue, educators and students wore green, writers wore white and purple, and artists wore pale rose.

Being the media-savvy women that they were, suffragists realized that it wasn’t enough to create an appealing impression of themselves. They also needed to come up with a recognizable brand. Inspired by the British suffragettes and their campaign colors – purple, white and green – the National Woman’s Party also adopted a set of three colors: purple, white and golden yellow.

They replaced green with yellow to pay tribute to Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who used the sunflower – Kansas’s state flower – when they campaigned for a failed statewide suffrage referendum in 1867.

Crafting a contrast

These American suffrage colors – purple, white and yellow – stood for loyalty, purity and hope, respectively. And while all three of them were used during parades, it was the brightness of the white that left the biggest impression.

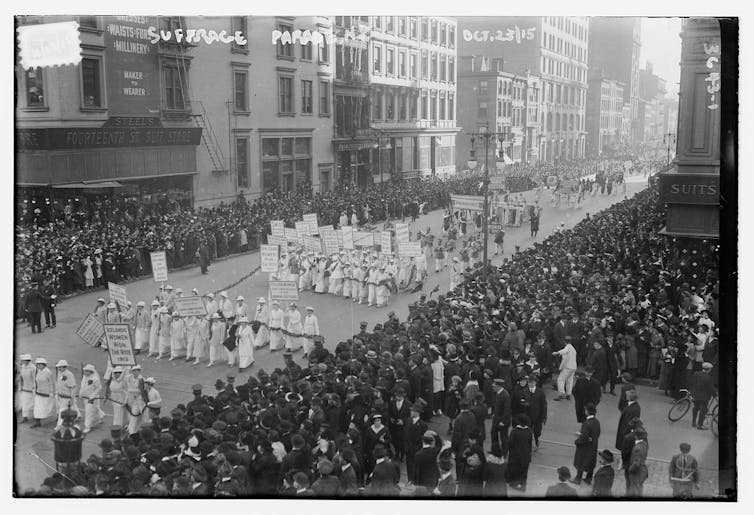

In images of suffragists marching in formation, their bright clothing contrasts sharply with the crowds of men in dark-colored suits who line the sidewalks.

This visual contrast – between women and men, bright and dark, order and disorder – conveyed hope and possibility: How might women improve politics if they get the right to vote?

White dresses were also easier and cheaper to attain than colored ones. A poorer or middle-class woman could show her support for suffrage by wearing an ordinary white dress and adding a purple or yellow accessory. The association of white with the idea of sexual and moral purity was also a useful way for suffragists to refute negative stereotypes that portrayed them as masculine or sexually deviant.

Black suffragists, in particular, capitalized on the association of white with moral purity. By wearing white, black suffragists showed they, too, were honorable women – a position they were long deprived of in public discourse.

Beyond the struggle for the vote, black women would deploy white. During the 1917 silent parade to protest lynching and racial discrimination, they wore white.

As much as white made a powerful statement, it was the combination of the colors – and the qualities that each represented – that reflect the true scope and symbolism of the suffrage movement.

The next time a female politician wants to use fashion to celebrate the legacy of the suffrage movement, it might be a good idea to not just emphasize their moral purity, but to also bring attention to their loyalty to the cause and, more importantly, their hope.

White is a great gesture. But it can be even better if there’s a dash of purple and yellow.

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

How the Emerald Isle shaped the Steel City – Pittsburgh’s rich Irish history

Long before Pittsburgh’s modern Irish celebrations existed, Irish immigrants helped shape the city…

As the Oscars approach, Hollywood grapples with AI’s growing influence on filmmaking

AI tools can now generate movie scenes, resurrect lost footage and replace entry-level jobs – forcing…

Nearly 1 in 3 missing children in the US are Black, driving Pennsylvania and other states to propose

Black children who go missing are often labeled as runaways, which excludes them from the Amber Alert…