What big data can tell us about how a book becomes a best-seller

It's easier to make the list than you might think.

The average American reads 12 or 13 books a year, but with over 3 million books in print, the choices they face are staggering.

Despite the introduction of 100,000 new titles each year, only a tiny fraction of these attract a large enough readership to make The New York Times best-seller list.

Which raises the questions: How does a book become a best-seller, and which types of books are more likely to make the list?

I’m a data scientist. Recently, with help of Burcu Yucesoy, a postdoc in my lab, I put the reading habits of Americans under our data microscope.

We did so by analyzing the sales patterns of the 2,468 fiction and 2,025 nonfiction titles that made The New York Times best-seller list for hardcovers during the last decade.

Real lives, imaginary action

The first thing the data reminded me is just how few books in my favorite category, science, become best-sellers – a paltry 1.1 percent. Science books compete for a spot on the nonfiction list with everything from business to history, sports to religion.

Yet, on the whole, hardcovers in these categories don’t fly off the shelves, either.

Which nonfiction titles do? Memoir and biographies, with almost half of the 2,025 nonfiction best-sellers falling into this category.

Then we examined the fiction list. Much of the press focuses on literary fiction – books we see debated by critics, lauded as important and culturally relevant, and eventually taught in schools.

But in the past decade, only 800 books categorized as literary fiction made the best-seller list. Most best-sellers – 67 percent of all fiction titles – represent plot-driven genres like mystery or romance or the kind of thrillers that Danielle Steel and Clive Cussler write.

Action sells – there’s no surprise there.

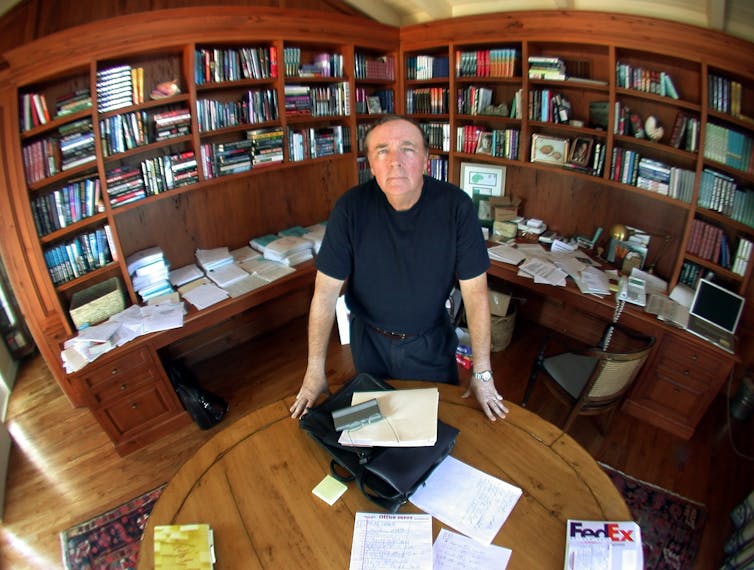

But it was unexpected the degree to which only a handful of authors repeatedly appear: Eight-five percent of best-selling novelists have landed multiple books on the list. Mystery and thriller novelist James Patterson, for example, had 51 books on the best-seller list in the period we explored.

By contrast, only 14 percent of nonfiction authors had more than one best-selling book. Perhaps this is because the genre often requires expertise on a specific subject matter. If an author primarily writes about football, or neuroscience, or even her own life, it’s difficult to generate 10 books on the topic.

A universal sales curve

Publishers eagerly slap “New York Times Bestseller” stickers on each book that appears on the list’s 15 slots.

A quarter of those, however, have only a cameo appearance, briefly grabbing a spot at the bottom of the list and dropping out after a single week. Only 37 percent have some staying power and spend more than four weeks on the best-seller list. Even fewer – 8 percent – attain the number one spot.

Some rare exceptions can lease out a spot for years: “The Help” by Kathryn Stockett lingered on the fiction list for an astonishing 131 weeks, while Laura Hillenbrand’s “Unbroken” stayed on the nonfiction list for a record 203 weeks.

One big misconception is that you have to write a mega-seller to make the list. The majority of titles on The New York Times best-seller list only sell between 10,000 and 100,000 copies in their first year. “The Slippery Year,” a 2009 memoir by Melanie Gideon, made the list with a yearly sale of fewer than 5,000 copies.

How is this possible?

Our data set shows that just about your only chance of making the list is right after your publication date.

That’s because book sales, we discovered, follow a universal sales curve – there’s a single mathematical formula that captures the weekly sales of all books. And that sales curve has a prominent peak right after the release, meaning you sell the most copies during the first weeks after your book’s release. Fiction sales almost always peak within the first two to six weeks; for nonfiction, the peak can come any time during the first 15 weeks.

While you might assume that there would be overlooked books that build their audiences slowly and eventually make it onto the hallowed list, there really aren’t.

It’s all about the timing

In other words, what happens during a brief window of time can foretell a book’s success.

For this reason, the timing of the release matters a great deal, especially since the threshold to reach the list varies throughout the year.

In February or March, selling a few thousand copies can land a book on the best-seller list; in December – when sales skyrocket during the holidays – selling 10,000 copies a week might not guarantee a book a spot.

So when should authors publish?

It depends on their circumstances. If they lack a strong fan base, and their hope is to simply make it onto the best-seller list, it’s best to aim for February or March.

At the same time, appearing on The New York Times best-seller list doesn’t necessarily guarantee that a book will sell more copies. Research shows that appearing on the list tends to boost sales only for unknown authors, and the effect disappears after one to three weeks.

So for well-known authors or celebrities who already have built-in fan bases, appearing on the best-seller list might not matter as much. Instead, they’ll likely want to maximize sales – in which case, it’s best to publish in late October: The release will coincide with peak sales in December, when bookstores are packed with Christmas shoppers.

The good news is that if you’re like me – and have written several books that didn’t end up as best-sellers – you still have a chance to break through: Our analysis shows that only 14 percent of novelists made the list with their first book.

Barabási's research laboratory is funded by several U.S. Federal Agencies and Foundations, and EU Funding Agencies. He is also affiliated with Harvard Medical School and Central European University in Budapest, Hungary.

Read These Next

Cuba’s speedboat shootout recalls long history of exile groups engaged in covert ops aimed at regime

From the 1960s onward, dissident Cubans in exile have sought to undermine the government in Havana −…

Nanoparticles and artificial intelligence can help researchers detect pollutants in water, soil and

Tiny particles bounce light around in a unique way, a property that researchers are using to detect…

Tiny recording backpacks reveal bats’ surprising hunting strategy

By listening in on their nightly hunts, scientists discovered that small, fringe-lipped bats are unexpectedly…