Can pink really pacify?

Famously feminized by the Nazis – and later used in prison cells to limit aggression in inmates – the color pink toes a shaky line between social psychology and gender stereotyping.

As an interior designer, I’ve long been interested in how different colors can affect our mood and behavior.

For example, if you’ve recently been to a fast food restaurant, you might notice that there’s a lot of red – red chairs and red signs, red trays and red cups.

When, on the other hand, was the last time you ate in a blue restaurant?

There’s a reason for this: Red, it turns out, has been shown to stimulate the appetite. Blue, on the other hand, has been shown to be an appetite suppressant.

But when it comes to interior design, the color pink has been particularly controversial.

After some psychologists were able to show that certain shades of pink reduced aggression, it was famously used in prison cells to limit aggression in inmates. Yet pink toes a shaky line. Is it a benign means of subtle manipulation? A tool to humiliate? An outgrowth of gender stereotyping? Or some combination of the three?

Pink is for girls?

When most people read that some are using pink to reduce aggression, they probably think, “of course.”

After all, from birth pink is appropriated to pretty little baby girls and blue is assigned to bouncing baby boys. In human psychology, we have come to connect the color to femininity and its corresponding gender stereotypes: weakness, shyness and tranquility.

But according to architectural historian Annmarie Adams, pink didn’t always automatically signal femininity. Pink became the default color for all things girly only after World War II. Before then, it was common for girls to wear blue, while mothers would often dress their boys in pink.

Adams traces the switch back to Nazi Germany. Just as the Nazis forced Jewish people to wear a yellow badge to identify themselves, they forced gay men to wear a pink badge. Ever since then, pink has been thought of as a non-masculine color reserved for girls.

Prisons go pink

Once pink started to embody femininity, some wondered if it could be used to “tame” aggressive male behavior.

Beginning in the 1980s, a handful of prison wardens painted holding cells in prisons and jails pink. The hope was that the color would have a calming effect on the male prisoners.

The wardens were inspired by the results from a series of studies conducted by research scientist Alexander Schauss. Schauss had concocted a pink paint color that he claimed could reduce the physical strength and aggressive tendencies of male inmates.

In his study, Schauss had subjects stare at a large square of pink paper with their arms outstretched. Then he tried to force their arms back down. He demonstrated he could easily do this as the color had weakened them. When he repeated the same experiment with a square of blue paper, their normal strength had returned.

Schauss named the color “Baker-Miller Pink” after two of his co-experimenters, naval officers Gene Baker and Ron Miller. Baker and Miller were so impressed with Schauss’ findings that they went ahead and painted the holding cells at their naval base this shade of pink. They raved about the results and how it had pacified inmates.

As word got around about the benefits of pink décor, psychiatric units and other holding areas were painted Baker-Miller Pink. Custodians reported quieter inmates and less physical and verbal abuse.

The Swiss go for a ‘cooler’ pink

All this seems like a simple, cost-effective solution to calm inmates.

However, a few years later, Schauss decided to repeat the experiments – only to find that Baker-Miller Pink didn’t have a calming effect on inmates after all.

In fact, after conducting a test in an actual pink cell, he noticed no difference in inmates’ behavior. He was even concerned that the color could make them more violent. It should be noted Baker-Miller Pink is not a pale, gentle, pastel pink. Instead, it’s a bright, hot pink.

Some 30 years later, psychologist Oliver Genschow and his colleagues repeated Schauss’ experiments. They carried out a rigorous experiment to see if Baker-Miller Pink reduced aggressive behavior in prison inmates in a detention center cell. Like Schauss’ later work, they found no evidence that the color reduced aggressiveness.

That might have been the end of the discussion on the benefit of pink cells. But in 2011, a Swiss psychologist named Daniela Späth wrote about her own experiments with a different shade of pink paint.

She called her shade “Cool Down Pink,” and she applied it to cell walls in 10 prisons across Switzerland.

Over the course of her four-year study, prison guards reported less aggressive behavior in prisoners who were placed in the pink cells. Späth also found that the inmates seemed to be able to relax more quickly in the pink cells. Späth suggests that Cool Down Pink could have a variety of applications beyond prisons – in airport security areas, schools and psychiatric units.

One British newspaper reported that prison guards were happy with the effects of Cool Down Pink, but prisoners were less so. The newspaper interviewed a Swiss prison reformer who said it was degrading to be held in a room that looked like “a little girl’s bedroom.”

Benign manipulation or outright humiliation?

Herein lies the crux of the controversy. Opponents of the practice say that the implication that the color – with its feminine associations – will somehow reduce aggression is, in and of itself, sexist and discriminatory. Gender studies scholar Dominique Grisard has argued that the pink prison walls – regardless of whether they pacify – are ultimately designed to humiliate male prisoners.

Famously, in the 1980s, the University of Iowa football team painted the visitors’ locker room at Kinnick Stadium pink. A 2005 refurbishment added pink lockers and even pink urinals.

The reasoning behind using the pink shade, officially named “Dusty Rose,” was much the same as that of the prison wardens: The coach, Hayden Fry, believed it would curtail the aggression of the opposing players and allow the home team to gain a competitive edge.

Yet like the prisons, this could be having the unintended, opposite effect. Some opposing players have reported being more fired up by the perceived insult of the pink locker rooms.

And so the debate about the power of pink rages on.

That hasn’t stopped some from trying to deploy pink to achieve tranquility in their homes. In 2017, model Kendall Jenner painted her living room Baker-Miller Pink – and raved about how it made her feel much calmer.

Who knows how many of her army of fans have followed her advice. For my part – although I love pink – I shudder at the thought of a hot pink living room, no matter how powerful its calming effects.

Julie Irish does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

How protecting wilderness could mean purposefully tending it, not just leaving it alone

For decades, wilderness lands have been left largely unaltered by human activity. But those places are…

Algorithms that customize marketing to your phone could also influence your views on warfare

AI systems are getting good at optimizing persuasion in commerce. They are also quietly becoming tools…

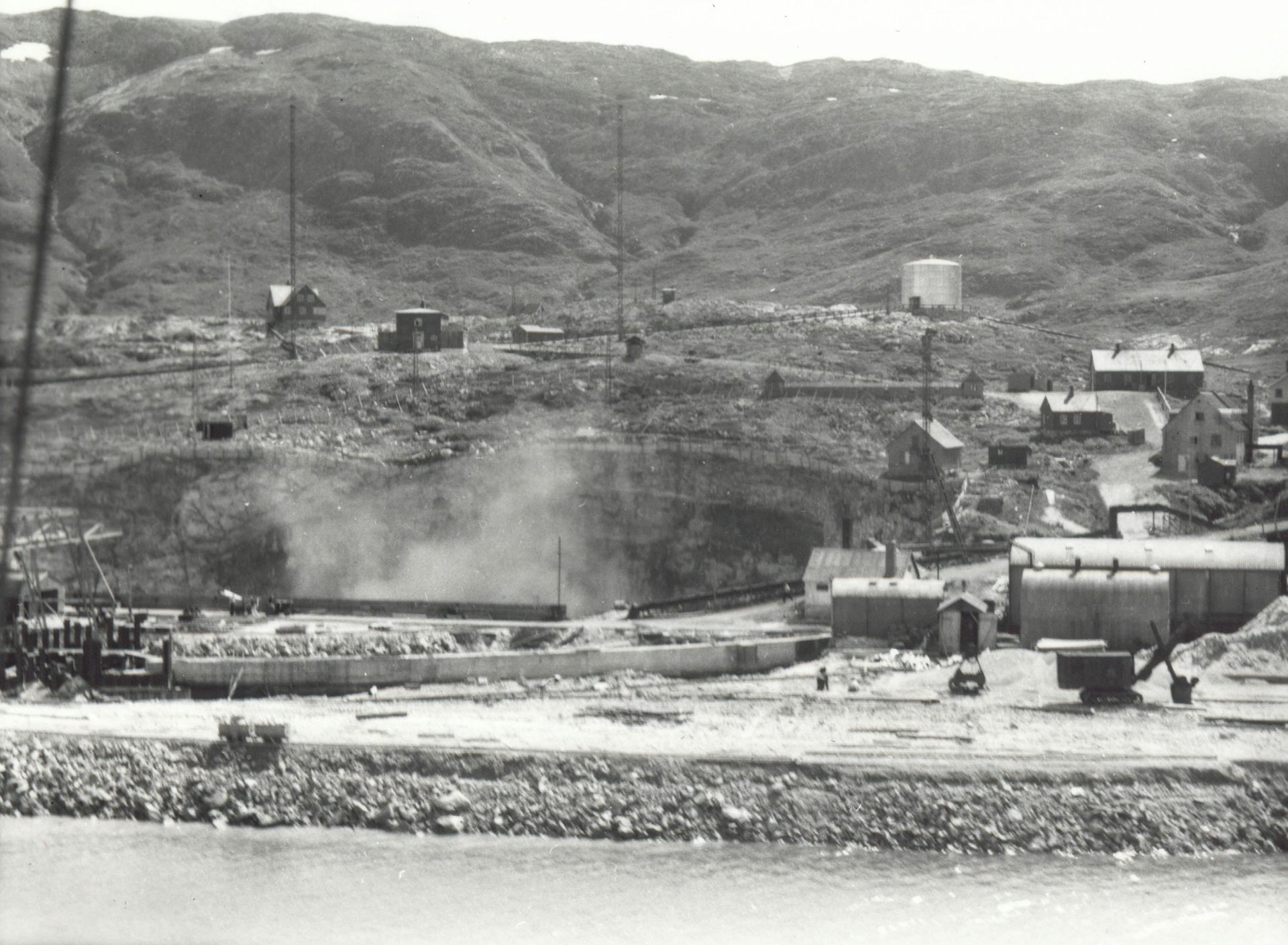

In World War II’s dog-eat-dog struggle for resources, a Greenland mine launched a new world order

Strategic resources have been central to the American-led global system for decades, as a historian…