#MeToo on the 1930s silver screen

Scores of Depression-era films depicted a pattern of sexual harassment that sounds all too familiar.

Time’s 2017 Person of the Year was “The Silence Breakers,” a growing contingent of women who have been speaking out about sexual harassment by men in positions of power.

But the sexual exploitation of women is hardly something new. As Time observed, the #MeToo movement “has actually been simmering for years, decades, centuries.”

In order to prepare for a course I’ll be teaching next fall about working women in 1920s and 1930s films, I’ve been watching a lot of movies from the period. And I’ve been repeatedly surprised by how much casual sexual harassment – a term that wouldn’t exist until decades later – was depicted on screen during those years.

In recent months, we’ve seen the exploitative behavior of powerful men exposed. But these movies from the 1930s show how far back these perverse values go, and how integral they were to Hollywood’s imagining of women’s lives.

A familiar pattern emerges

In 1934, the Motion Picture Association of America adopted a Production Code that suppressed representations of sex and violence.

In the years before the code began to be enforced, filmmakers frequently depicted sexual coercion on the big screen.

Many of these films took place in a Depression-era urban milieu. They featured unmarried, working class women struggling to pay the rent, mend their worn out stockings, and decide between dinner or carfare. And in movies from “Millie” (1931) to “The Week-End Marriage” (1932) there’s a familiar pattern of sexual aggression towards these women.

A male shop owner, business executive, restaurant patron or department store customer promises a woman resources – nice clothes, a fancy apartment, career advancement – or marriage (once their wives divorce them, of course). In exchange, they want sex. Maybe it’s just for a weekend; maybe it’s for longer.

When the men get what they want, their initial promises – marriage, a better job, a life of luxury – usually dry up.

For the predators in these movies, consequences are almost always nonexistent. The men casually presume their right to the bodies of these young, beautiful women, banking on their literal hunger and economic desperation. The harassed, on the other hand, typically suffer for their optimistic (some might say foolish) hope that love or decency might win out in the end.

Harassment, heartbreak, suicide

These repeated incidences of sexual exploitation appear to be commonplace, even expected.

Female characters are rarely surprised when men grope or solicit them. Instead, they offer well-rehearsed (and often hilarious) cracks as they commiserate with each other in the aftermath. A joke, repeated in several films, is the “no sale” icon popping up at the cash register after a female character rejects a pass.

Some female characters – like Fay (Ginger Rogers) and Trixie (Aline MacMahon) in “Gold Diggers of 1933” (1933) – are savvy about their sexual currency, seeking relationships with otherwise undesirable men to gain access to their wallets. Others, like Lily (Barbara Stanwyck) in “Baby Face” (1933), use men’s relentless advances to build their careers, turning sex into a tool for economic ascension.

But for every Trixie and Lily, there are a host of devastated women who fall victim to male deception, some to the point of committing suicide.

“Our Blushing Brides” (1930) tells the story of a trio of department store models. Connie (Anita Page), falls in love with a wealthy man who leads her to believe he’s going to marry her, showering her with the finer things in life and a swanky apartment in exchange for you-know-what.

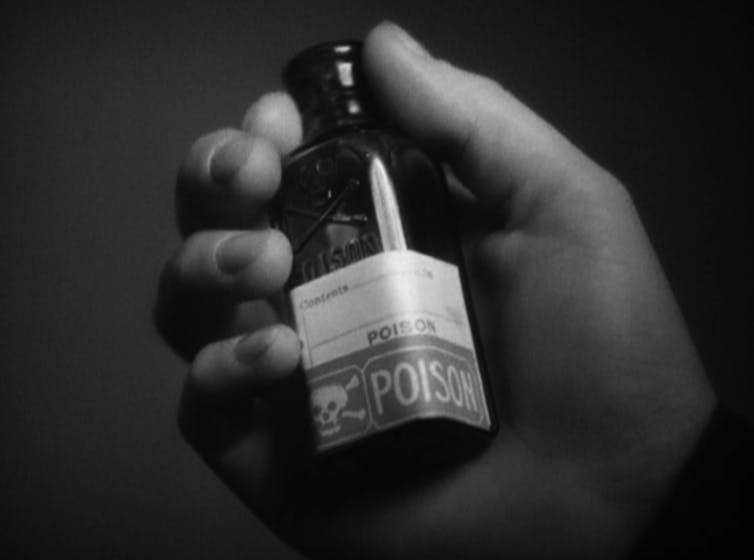

It turns out that Prince Charming plans to marry another woman, one of his class. Heartbroken and ashamed, Connie listens to the wedding broadcast on the radio. Then she quaffs poison.

“Three Wise Girls” (1932) opens with Cassie (Jean Harlow) walking alone at night on a dark country road. A male driver stops and offers her a ride, to which Cassie cracks: “No thanks, I’m just walking home from one.”

From the start, this is a film about the nonstop diligence required to avoid sexual victimization. Cassie moves to New York hoping to rise in the world, and ends up working at a soda fountain. Her boss slides behind her as she’s pouring a soda, lingering with his hands on her until she brushes him away. Seconds later, we hear Harlow slap him in the back room and shout, “Take your hands off me.” Needless to say, that’s the end of that job.

A wealthy drunk who observes this encounter follows Cassie out of the store, offering her a ride in his car, saying he needs the air.

“Yeah, well I’m giving you the air,” Cassie replies.

That makes three passes in the film’s first 10 minutes, and that’s the tip of the iceberg.

Toward the end of the film, one of the other (not so) wise girls, Gladys (Mae Clarke), finds out from a newspaper headline that her beau has reconciled with his wife.

“Not a note, telephone call, anything. I had to read it in the papers,” she tells Cassie, before collapsing.

Moments later, Cassie finds the bottle of poison Gladys used to commit suicide.

Same as it ever was?

In the midst of our current cultural reckoning with sexual harassment, it’s worth considering what these films communicated.

Much like their #MeToo counterparts today, some of these female characters manage to ward off their pursuers, even when they’re the boss. However, just as often they pay the price with their jobs or, as in the aforementioned examples, their lives.

Is it surprising that Hollywood is rife with the real-life version of these stories, which are only now coming out and being taken seriously?

Moviegoers in the early 1930s watched films about such sexual aggression on a regular basis, suggesting the degree to which this behavior was known, if not tacitly condoned, by film producers who were, of course, all male. The Production Code certainly tamed such blunt plot lines.

But the residue of men using their power to exert control over women (especially those economically beneath them) remained, albeit in muted forms. One can only imagine how many Harvey Weinsteins operated with impunity in 1930s Hollywood.

As Lily says to Courtland Trenhold (George Brent) in “Baby Face,” “I was hoping you wouldn’t be like everybody else. Silly of me, wasn’t it?”

Marsha Gordon ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son poste universitaire.

Read These Next

Iran will respond to US-Israeli strikes as existential threats to the regime – because they are

The latest attack on Iran goes far beyond previous operations by Israel and the US in both scale and…

Nanoparticles and artificial intelligence can help researchers detect pollutants in water, soil and

Tiny particles bounce light around in a unique way, a property that researchers are using to detect…

Tiny recording backpacks reveal bats’ surprising hunting strategy

By listening in on their nightly hunts, scientists discovered that small, fringe-lipped bats are unexpectedly…