For black celebrities like Oprah, it's impossible to be apolitical

Throughout American history, being a black celebrity has been a political act in and of itself. When viewed through this lens, the transition into politics for someone like Winfrey is more natural.

Oprah Winfrey’s rousing Golden Globe speech has many speculating whether the media mogul will become a presidential candidate in 2020, with some pundits questioning the merits of another “celebrity” president.

But to equate Oprah with other “celebrity” politicians like Donald Trump and Arnold Schwarzenegger skirts the history of how black celebrities have long assumed political roles – often unintentionally – within the black community.

When it’s viewed through this lens, the transition into politics for someone like Winfrey is more natural. Oprah, for her part, seems to understand the tremendous importance of high-profile blacks in American society. During her monologue, she became emotional when she described how, as a young girl, she watched Sidney Poitier receive the Cecil B. DeMille Award at the 1964 Golden Globes – “I’d never seen a black man being celebrated like that.”

But the ability of black celebrities to symbolize hope and racial progress precedes Poitier. The black singers, actors and athletes of the 1930s and 1940s weren’t simply entertainers; they were living proof that African-Americans didn’t need to succumb to racist stereotypes, and could be treated with dignity, even deference. With structural racism embedded in the nation’s social and economic fabric, this, in and of itself, was a political act.

As I point out in my book “Black Culture and the New Deal,” during the Great Depression and World War II, the U.S. government recognized the political potency of the black celebrity, and would tap into this power to project a democratic ethos at home and abroad.

Elevating the black cultural hero

By the time Franklin D. Roosevelt decided to seek a second presidential term in 1936, African-American voters had become an important demographic for the Democratic Party. But with white Southerners comprising a significant part of Roosevelt’s base, segregation and discrimination were more difficult for the government to directly confront.

Roosevelt still needed to figure out a way to reach out to the black community. So instead of passing legislation to correct racial inequality, his administration developed cultural programs that would employ large numbers of black men and women, and promote the skills and abilities of African-Americans.

For example, New Deal Arts programs included individuals such as Carlton Moss, Sterling Brown and Zora Neale Hurston to create books and plays that would depict African-Americans in sympathetic, humane ways. The Federal Writers’ Project’s American Guide Series, which Brown edited, highlighted the diversity of African-American communities and customs. The Federal Theater Project featured plays written and directed by black men and women that grappled with pressing racial issues.

This was a potent political tool; federal officials understood that African-Americans would be deeply affected – as Winfrey later was when watching Poitier receive the DeMille Award – by seeing African-Americans portrayed in more realistic and respectful ways.

A message of unity and freedom

The stakes became even greater as America entered World War II. Simmering racial tensions needed to be reconciled with America’s democratic, anti-fascist ideals.

Cultural programs promoting racial cooperation abounded within war agencies. Office of War Information posters and Hollywood films such as “Bataan” featured white and black men working and fighting together.

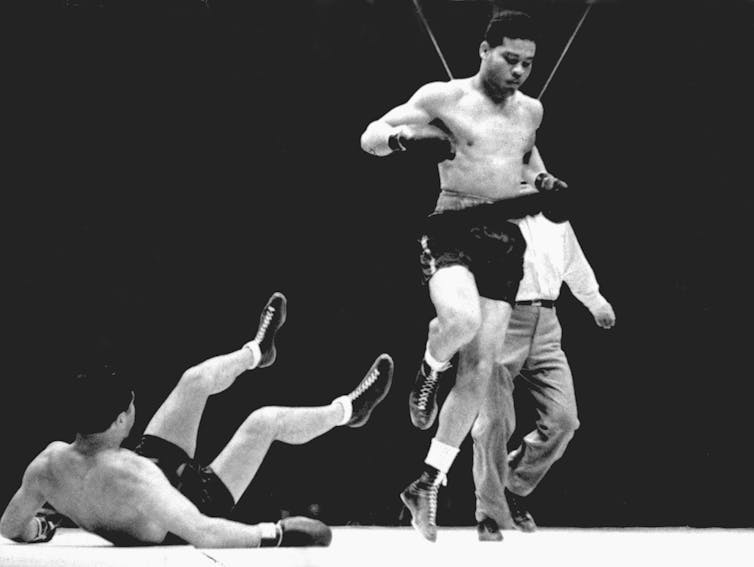

But no one was more central to this brand of propaganda than boxer Joe Louis.

In 1938, Louis had stunned the world by defeating German Max Schmeling. Geopolitically, it was a display of American superiority. But for African-Americans it was a triumph over whites.

Unassuming and apolitical, Louis didn’t ever talk about racial issues. Nonetheless, he became a hugely important political figure.

Poet Maya Angelou wrote of Louis’ victories as evidence that African-Americans were the “strongest people in the world”; novelist Richard Wright described Louis’ victories as “a fleeting glimpse … of the heart that beats and suffers and hopes for freedom.”

Recognizing Louis’ profound appeal, the government quickly swooped in, employing him in the Army’s Morale Division to boost patriotism among African-Americans during World War II.

As one government official noted in 1942, “It might be well to ask the questions as to who would draw the biggest audiences, Joe Louis or [NAACP Executive Secretary] Water White. The answer is obvious.”

During his 46 months in the Army, Louis partook in 96 exhibition fights in the U.S. and abroad as part of a troupe that included black boxers George C. Nicholson, Sugar Ray Robinson and George J. Wilson. He also appeared on posters and in films that promoted racial inclusion, such as “The Negro Soldier.”

Louis wasn’t the only black cultural hero to play a political role during the war. The Armed Forces Radio Service created a program featuring black musicians called “Jubilee.” Lena Horne, Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington and others appeared in this weekly program that was broadcast domestically and to servicemen abroad. It reassured black troops on the front lines, while many white soldiers were able to listen to musicians they had never heard before.

The power of the stage

These federal efforts during the Great Depression and World War II are complicated. One the one hand, it could be argued that they represented a tokenistic appeal to African-Americans in lieu of real social and economic change. On the other, there’s no doubt that African-Americans were given the opportunity to be themselves, be celebrated, and move beyond the demeaning stereotypes that had existed for decades.

In the postwar period, civil rights leaders challenged African-American celebrities to use their platform to promote racial equality. Some, like Muhammad Ali, famously called for change, while others were more reticent. But the political stance of these individuals may not have mattered as much as their visibility and success. As filmmaker Ezra Edelman argues in his 2016 documentary “O.J.: Made in America,” even as Simpson insisted that we was “not black, just O.J.,” he was still embraced by the black community, and lauded as an African-American hero.

After centuries of degradation and discrimination, the accomplishments of African-Americans like Simpson or Oscar winner Hattie McDaniel possessed a political resonance. Though they were reluctant to promote racial change, by succeeding in traditionally exclusionary industries, they nonetheless became political figures. They signaled to other African-Americans that barriers could be broken down. Even if they weren’t activists themselves, they inspired others to fight inequality.

As a black woman, Oprah Winfrey occupies a unique space in this legacy of cultural heroes. Though it remains to be seen whether her candidacy will become a reality, she knows the significance of her actions for people of color in the U.S. and around the world. At a time when black women remain marginalized, Oprah – media mogul, actress, philanthropist, tastemaker – embodies the American Dream. People still look to cultural figures as much as they look to politicians for inspiration.

As Oprah stated in her speech, her life and career demonstrate how “we can overcome.”

Lauren Rebecca Sklaroff has received funding from National Endowment of the Humanities. She is an Associate Professor of History at the University of South Carolina.

Read These Next

The nation is missing millions of voters due to lack of rights for former felons

At least 20 million Americans have served time. Most of them can’t or don’t vote, and that may distort…

Why are so many statues naked? An art historian explains this tradition’s ancient roots

Nudity can express everything from innocence to sexual desire, from triumph to defeat.

Kansas revoked transgender people’s IDs overnight – researchers anticipate cascading health and soci

With invalid driver’s licenses and birth certificates, transgender people are at risk for more than…