From cowboys to commandos: Connecting sexual and gun violence with media archetypes

With mass shootings and sexual harassment reports on the rise, a psychologist reflects on how the evolving nature of male role models in the media may be contributing.

If you feel as if there’s been an uptick in the frequency and lethality of mass shootings in recent years, you’re not imagining it. The time between mass shootings (involving four or more casualties) in the U.S. has been shrinking since the 1990s, and the death rate in these massacres has almost tripled since 2000.

And if it also seems that reports of sexual assault on the part of celebrities, politicians and journalists are coming in almost daily, you are, once again, not mistaken. It is probably not coincidental that the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network reports “a record number of survivors [who] turned to RAINN for help,” with a 26 percent increase in hotline traffic in November alone.

No, I’m not equating sexual assault and mass murder. But as a psychiatrist, I think there is an indirect connection between the rising rates of each. To understand why, we need to explore the shifting media role models to which young American males have been exposed since the 1950s and ‘60s. As sociologist Daniel Rios Pineda has observed, the influence of the mass media begins at a very early age. Based on my own cultural observations, I believe that the emergence of a more violent male “archetype” in the media has been internalized by many young men, and may be one factor contributing to increased sexual and gun-related violence.

The cowboy’s code

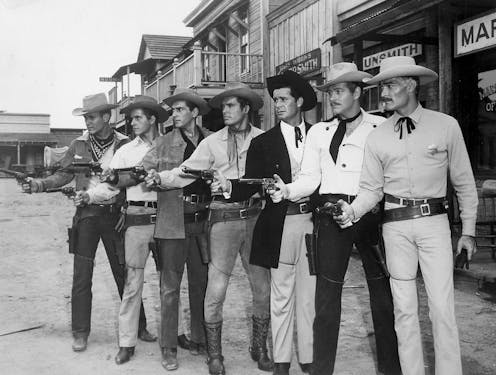

Once upon a time, the archetype of the cowboy stood tall in the American male psyche. Growing up in the 1950s, my friends and I had plenty of admirable cowboy role models, drawn from TV Westerns like “Gunsmoke,” “The Rifleman” and “The Life And Legend Of Wyatt Earp.” Broadly speaking, the heroes of these shows were decent, honorable and law-abiding individuals, trying to survive in dangerous times. Early TV Westerns aimed to teach the values of honesty, integrity, hard work, racial tolerance and justice for all.

I don’t mean to claim that the cowboy archetype is totally supportive of today’s progressive values. For many Native Americans, the term “cowboy” probably evokes distasteful images. For some feminists, the archetype may seem exclusionary and patriarchal, representing an idealized (and violent) male vision of the “Old West.”

Nevertheless, the real American West reflected some progressive ideals, often enshrined in law. For example, in contrast to today’s clamor for unrestricted “gun rights,” pioneers in the American West established many regulations designed to reduce gun violence. According to historian Ross Collins:

“Pioneer publications show Old West leaders repeatedly arguing in favor of gun control. City leaders in the old cattle towns knew from experience what some Americans today don’t want to believe: a town which allows easy access to guns invites trouble.”

The Old West also had an unwritten code of ethics, sometimes called “the cowboy code.” Historian Ramon Adams, in his 1969 book, “The Cowman and His Code of Ethics” noted that one of the strictest codes of the West was “respect of womanhood.”

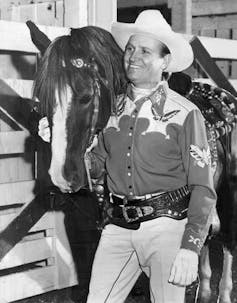

In the 1940s, famous cowboy Gene Autry developed his own version of the cowboy code, which included this notable commandment: “[The cowboy] must respect women, parents and his nation’s laws.” Though not explicitly aimed at a young audience, Autry’s code had a natural affinity with, for example, values promoted by the Boy Scouts of America.

In short, peaceable and law-abiding behavior – including respect for women – were integral parts of the early American West’s “cowboy ethos,” which many American boys of the mid-20th century tried to emulate as it reached them via Hollywood. As the Museum of Western Film History puts it, early TV Westerns “offered morality plays for the juvenile audience.”

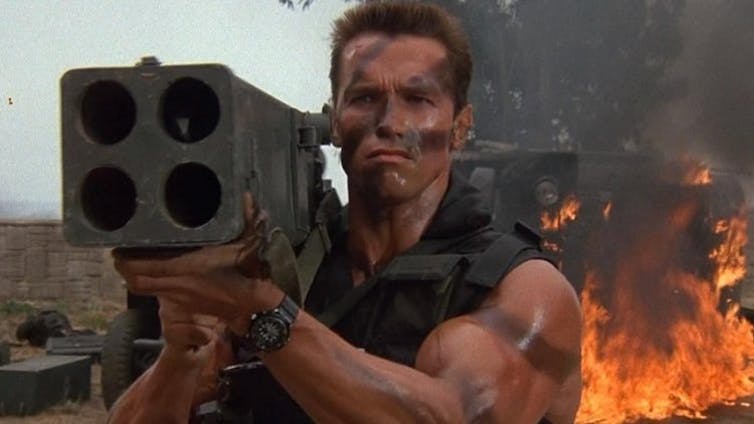

Commandos and pseudocommando killers

Unfortunately, as the cowboy receded into the sunset, he was gradually displaced in the 1980s – not long after the Vietnam War – by the far more violent figure of the commando. Enter John Rambo (played by Sylvester Stallone) and John Matrix (played by Arnold Schwarzenegger in the movie, “Commando”). As one reviewer put it, “Matrix just kills, kills, kills… If you look up 'gratuitous violence’ in the dictionary, you’ll see a link to ‘Commando.’”

Though the relationship between media violence and childhood aggression is controversial, child psychiatrist Eugene Beresin has observed that violent heroes become role models for youth. Psychologist and former Army Ranger Lt. Col. Dave Grossman sees a direct link between today’s violent and vengeful movie “heroes” and the mass killings at Columbine High School and Virginia Tech.

Indeed, I believe there’s a link between the cinematic archetype of the “commando” and the recent spate of “pseudocommando” killings in the real world. According to my colleague, forensic psychiatrist James L. Knoll IV, the pseudocommando often kills indiscriminately; comes prepared with a powerful arsenal of weapons; has no escape plan; and harbors strong feelings of anger and resentment.

Psychologists believe the pseudocommando’s rage is fueled by a quest for power – usually in a desperate attempt to redress his deep-seated sense of powerlessness.

And herein lies the nexus with individuals who engage in sexual assault. These aggressive acts are fundamentally about power and control.

Link between sexual and gun-related violence

A number of studies support the view that most mass shootings in the U.S. are preceded by domestic or family violence – often directed against women. For example, both the Orlando Pulse club shooter and the Virginia Tech shooter had a history of abusing or harassing females prior to carrying out mass murder. The nonprofit group Everytown for Gun Safety analyzed mass shootings between 2009 and 2016 and found that in 54 percent of cases, the shooters killed intimate partners or other family members.

It must be said that men, too, may be victims of sexual violence, at the hands of either males or females. However, mass shootings are carried out almost entirely by men.

There are compelling reasons to believe that sexual and gun-related violence spring from the same cultural roots – a culture that lionizes and glorifies male aggression.

Thus, Charles M. Blow, in a recent New York Times op-ed, alluded to the “toxic, privileged, encroaching masculinity” that pervades American culture. He argued that our society has fostered the dangerous notion that aggression is a prized part of male sexuality. In effect, boys are encouraged to be aggressive, while girls become their victims.

Some caveats and qualifications

The causes of violence are complex and overdetermined. The two archetypes I’ve described are expressions of the zeitgeist of their respective eras, as much as they are forces that shape men’s psychological development. Furthermore, young males today are faced with many risk factors for violence, including abusive parents, bullying in school, and the allure of gangs. Psychologists believe that “no single risk factor consistently leads a person to act aggressively or violently.”

Nevertheless, I suggest that the confluence of the commando mentality and our culture’s way of raising boys and young men has contributed to an uptick in sexual and gun-related violence. Too often, young men learn that macho is cool and that you can get away with anything you want. And as the #MeToo movement demonstrates, these attitudes have infected men’s behavior at the highest levels.

The cowboy code may no longer be suited to our modern needs. But it is not too late to renounce the commando mentality, and to raise boys – as Gene Autry would have it – to respect both women and the nation’s laws.

Ronald W. Pies does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Local governments provide proof that polarization is not inevitable

Partisan debates are less heated at the local level, providing lessons that might help calm the waters…

‘Which Side Are You On?’: American protest songs have emboldened social movements for generations, f

Bruce Springsteen wrote and recorded ‘Streets of Minneapolis’ within days of Alex Pretti’s killing,…

As Jeff Bezos dismantles The Washington Post, 5 regional papers chart a course for survival

Other billionaires who own newspapers are doing a better job, a journalism professor explains.