Whether Netflix or Paramount buys Warner Bros., entertainment oligopolies are back – bigger and mor

Hollywood has seen this movie before.

News of Netflix’s bid to buy Warner Bros. last week sent shock waves through the media ecosystem.

The pending US$83 billion deal is being described as an upending of the existing entertainment order, a sign that it’s now dominated by the tech platforms rather than the traditional Hollywood power brokers.

As David Zaslav, CEO of Warner Bros. Discovery, put it, “The deal with Netflix acknowledges a generational shift: The rules of Hollywood are no longer the same.”

Maybe so. But what are those rules? And are they being rewritten, or will moviegoers and TV audiences simply find themselves back in the early 20th century, when a few powerful players directed the fate of the entertainment industry?

The rise of the Hollywood oligopolies

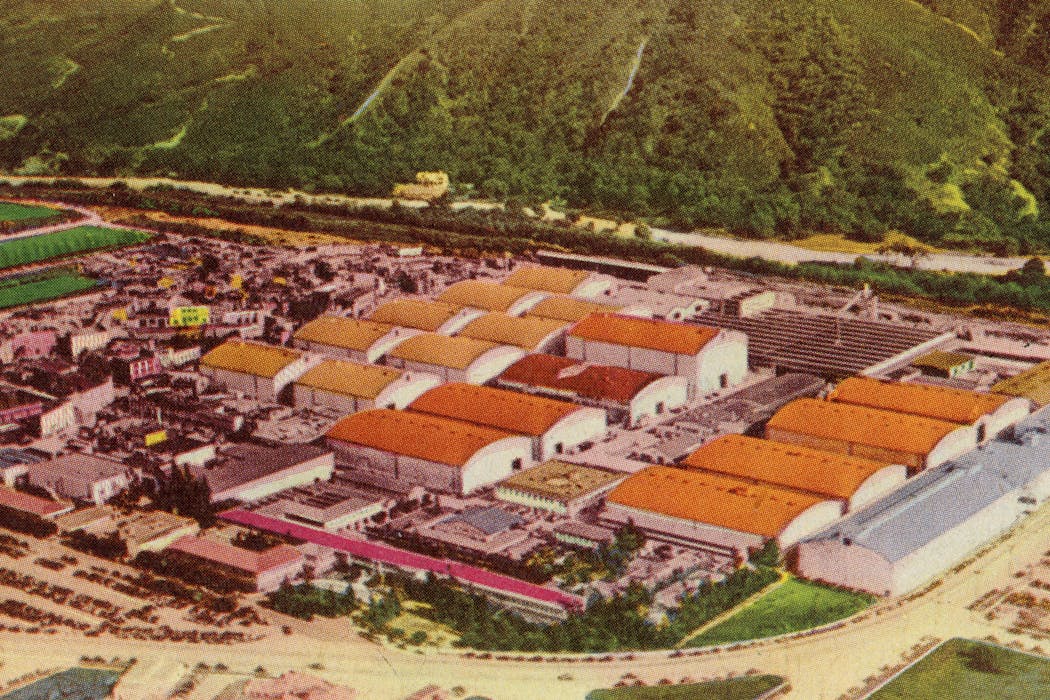

As Hollywood rose to prominence in the 1920s, theater chain owner Adolf Zuker spearheaded a new business model.

He used Wall Street financing to acquire and merge his film distribution company, Famous Players-Lasky, the film production company Paramount and the Balaban and Katz chain of theaters under the Paramount name. Together, they created a vertically integrated studio that would emulate the assembly line production of the auto industry: Films would be produced, distributed and shown under the same corporate umbrella.

Meanwhile, Harry, Albert, Sam and Jack Warner – the Warner brothers – had been pioneer theater owners during the nickelodeon era, the period from roughly 1890 to 1915, when movie exhibition shifted from traveling shows to permanent, storefront theaters called nickelodeons.

They used the financial backing of investment bank Goldman Sachs to follow Zucker’s Hollywood model. They merged their theaters with several independent production companies: the Vitagraph film distribution company, the Skouras Brothers theater chain and, eventually, First National.

But the biggest of the Hollywood conglomerates was Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, created when the Loews theater chain merged Metro Pictures, Goldwyn Pictures and Mayer Pictures.

At its high point, MGM had the biggest stars of the day under noncompete contracts and accounted for roughly three-quarters of the entire industry’s gross revenues.

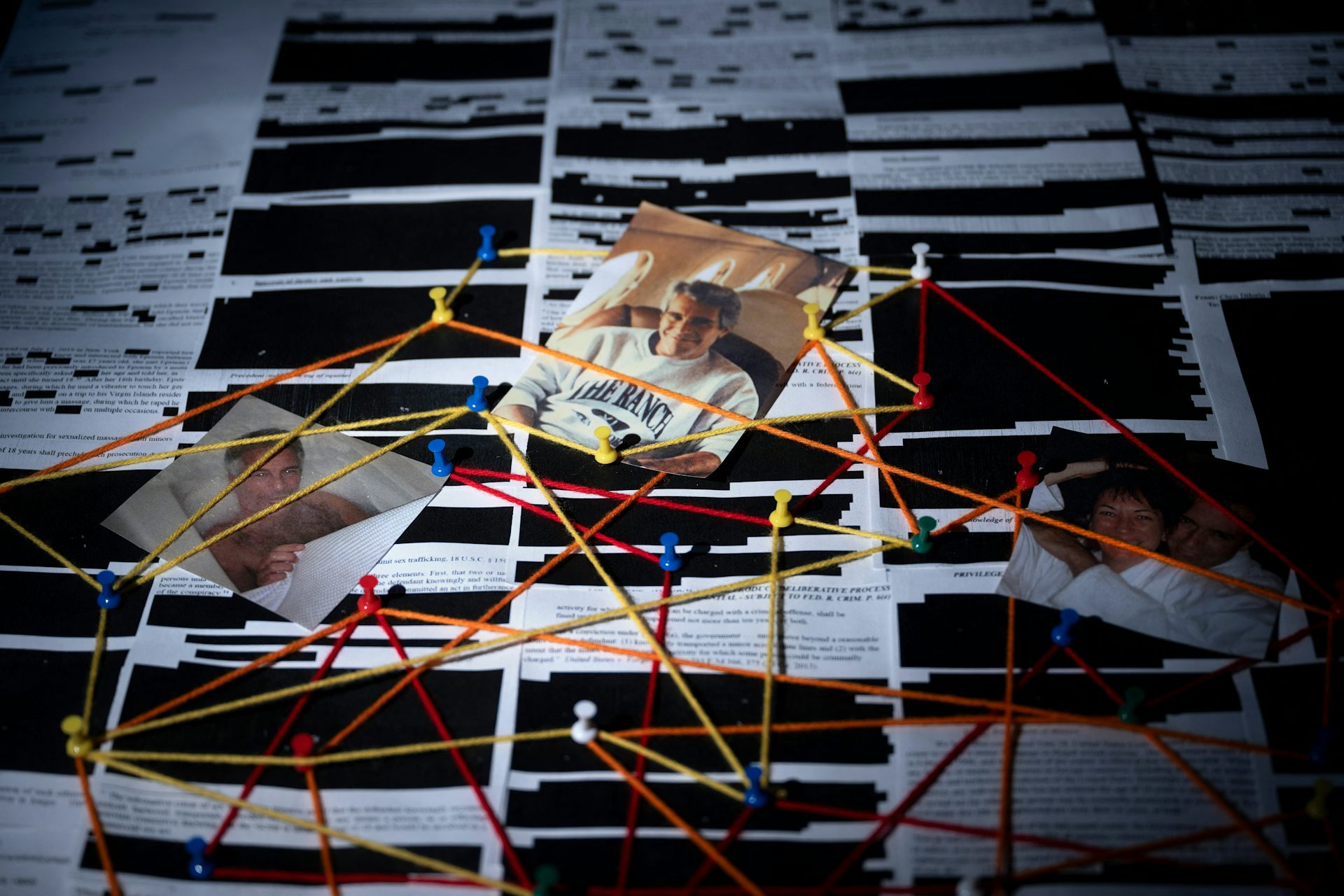

By the mid-1930s, a handful of vertically integrated studios dominated Hollywood – MGM, Paramount, Warner Brothers, RKO and 20th Century Fox – functioning like a state-sanctioned oligopoly. They controlled who worked, what films were made and what made it into the theaters they owned. And though the studios’ holdings came and went, the rules of the industry remained stable until after World War II.

Old Hollywood loses its cartel power

In 1938, the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission sued the “Big Five” studios, arguing that their vertically integrated model was anti-competitive.

After the Supreme Court decided in favor of the U.S. government in 1948 – in what became known as the Paramount Decision – the studios were forced to sell off their theater chains, which checked their ability to squeeze theaters and squeeze out independent producers.

With the studios’ cartel power weakened, independent filmmakers like Elia Kazan and John Cassavetes flourished in the 1950s, making pictures like “On the Waterfront” that the studios had rejected. Foreign films found their ways to American screens no longer constrained by block booking, a practice that forced exhibitors to pay for a lot of mediocre films if they wanted the good ones, too.

By the 1960s, a new generation of filmmakers like Mike Nichols and Stanley Kubrick scored big with audiences hungry for something different than the escapist spectacles Hollywood was green-lighting. They took risks by hiring respected writers and unknown actors to tell stories that were truer to life. In doing so, they flipped Hollywood’s generic formulas upside down.

A decade ago, I wrote about how Netflix’s streaming model pointed to a renaissance of innovative storytelling, similar to the period after the Paramount Decision.

By streaming their indie film “Beast of No Nation” directly to subscribers at home, Netflix posed a direct threat to Hollywood’s blockbuster model, in which studios invested heavily in a small number of big-budget films designed to earn enormous box office returns. At the time, Netflix’s 65 million global subscribers gave it the capital to produce exclusive content for its expanding markets.

Hollywood quickly closed the streaming gap, developing its own platforms and restricting access of its vast catalogs to subscribers.

Warner Bros. bought and sold

In 2018, AT&T acquired Time Warner, the biggest media conglomerate of the time, and DirectTV. It hoped to merge its 125 million-plus telecommunication customers with Time Warner’s content and create a streaming giant to compete with Netflix.

Then came the COVID-19 pandemic, and the theatrical model for film distribution collapsed.

The pressure on AT&T’s stock led the company to sell off HBO and WarnerMedia to Discovery in 2022 for $43 billion. Armed with the HBO and Warner Bros. libraries – along with the advertising potential of CNN, TNT and Turner Sports – CEO David Zaslav was bullish about the company’s potential for growth.

Warner Bros. Discovery became the third-largest streaming platform in terms of subscribers behind Netflix and Disney+, which had gobbled up 20th Century Fox.

But the results have been bad for audiences.

In 2023, Zaslav rolled out a bundled streaming platform called Max that combined the libraries of HBO Max and Discovery+, which ended up confusing consumers and the market. So it reverted back to HBO Max because consumers recognized the brand.

Zaslav then decided it was more cost effective to cancel innovative projects or write off completed films as losses. Zaslav often claims his deals are “good for consumers,” in that they get more content in one place. But conglomerates who defend their anti-competitive practices as signs of an efficient market that benefit “consumer welfare” frequently say that, even when they are making the product worse and limiting choices.

His deals have been especially bad for the television side, yielding gutted newsrooms and canceled scripted shows.

Effectively, in only three years, the Warner Bros. Discovery merger has validated nearly all the concerns that critics of “market first” policymaking have warned about for years. Once it had a dominant market share, the company started providing less and charging more.

Meet the new boss – same as the old boss

If it does go through, the Netflix-Warner Bros. merger will likely please Wall Street, but it will further decrease the power of creators and consumers.

Like other companies that have moved from being a growth stock to a mature stock, Netflix is under pressure to be profitable. Indeed, it has been squeezing its subscribers with higher fees and more restrictive login protocols. It’s a sign of what tech blogger Cory Doctorow describes as the logic of “enshittification,” whereby platforms that have locked in audiences and producers start to squeeze both. Buying the competition – HBO Max – will mean Netflix can charge even more.

After the Netflix deal was announced, Paramount joined forces with President Donald Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner, the Saudi Sovereign Wealth fund and others to announce a hostile counteroffer.

Now, all bets are off. Whichever platform acquires Warner Bros. will have enormous power over the kind of stories that get sold and told.

In either case, Warner Bros. would be bought by a direct competitor. The Department of Justice, under the first Trump administration, already pushed to sunset the Paramount Decision, claiming that the distribution model had changed to such an extent that it was unlikely that Hollywood could ever reinstate its cartel. It’s hard to imagine that Trump 2.0 will forbid more media concentration, especially if the new parent company is friendly to the administration.

No matter which bidder becomes the belle of Trump’s ballroom, this merger illustrates how show business works: When dominant platforms also own the studios and their assets, they control the fate of the movie business – of actors, writers, producers and theaters.

Importantly, the concentration is taking place as artificial intelligence threatens to displace many aspects of film production. These corporate behemoths will determine if the film libraries spanning a century of Hollywood production will be used to train the machines that could replace artists and creatives. And with each prospective buyer taking on over $50 billion in bank debt to pay for the deal, the new parent of Warner Bros. will be looking everywhere for profits and opportunities to cut costs.

If history is any guide, there will be struggles ahead for consumers and competing creatives. In a media system that has veered back to following Hollywood’s yellow brick rules of the road, the new oligopolies are an awful lot like the old ones.

Matthew Jordan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Why Stephen Colbert is right about the ‘equal time’ rule, despite warnings from the FCC

The ‘equal time’ rule has been around for a century and aims to promote broadcasters’ editorial…

As war in Ukraine enters a 5th year, will the ‘Putin consensus’ among Russians hold?

Polling in Russia suggests strong support for President Vladimir Putin. Yet below the surface, popular…

Supreme Court rules against Trump’s emergency tariffs – but leaves key questions unanswered

The ruling strikes down most of the Trump administration’s current tariffs, with more limited options…