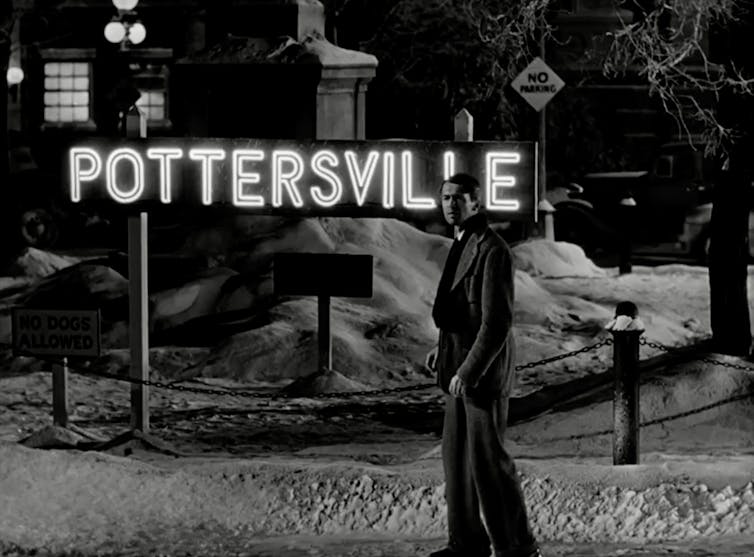

The dystopian Pottersville in ‘It’s a Wonderful Life’ is starting to feel less like fiction

Frank Capra’s dark vision of corruption and greed highlights both the dangers of concentrated power and the quiet effectiveness of collective action.

Along with millions of others, I’ll soon be taking 2 hours and 10 minutes out of my busy holiday schedule to sit down and watch a movie I’ve seen countless times before: Frank Capra’s “It’s a Wonderful Life,” which tells the story of a man’s existential crisis one Christmas Eve in the fictional town of Bedford Falls.

There are lots of reasons why this eight-decade-old film still resonates, from its nostalgic pleasures to its cultural critiques.

But when I watch it this year, the sequence where Bedford Falls transforms into the dark and dystopian “Pottersville” will resonate the most.

In the film, protagonist George Bailey, who’s played by Jimmy Stewart, is on the brink of suicide. He seems to have achieved the hallmarks of the American dream: He’s taken over his father’s loan business, married the love of his life and fathered four excessively adorable children. But George feels stifled and beaten down. His Uncle Billy has misplaced US$8,000 of the company’s money, and the town’s resident tyrant, Mr. Potter, is using the mishap to try to ruin George, who’s his last remaining business competitor.

An angel named Clarence is tasked with pulling George back from the brink. To stop him from attempting suicide, Clarence decides to show George what life would have been like if he’d never been born. In this alternate reality, Bedford Falls is called Pottersville, a place Mr. Potter runs as a ruthless banker and slumlord.

Having previously written about “It’s a Wonderful Life” in my book on literary and film censorship, I can’t help but see parallels between Pottersville and the U.S. today.

Think about it:

In Pottersville, one man hoards all the financial profits and political power.

In Pottersville, greed, corruption and cynicism reign supreme.

In Pottersville, hard-working immigrants like Giuseppe Martini who were able to build a life and run a business in Bedford Falls have vanished.

In Pottersville, homeless addicts like Mr. Gower and nonconformist “pixies” like Clarence are scorned and ostracized, then booted out of the local watering hole.

In Pottersville, cops arrest people like Violet Bick while they’re at work and haul them away, kicking and screaming.

But what horrifies George the most about Pottersville is how desensitized the people living in it seem to be to its harshness and cruelty – how they treat him like he’s the crazy, deranged one for wanting and expecting things to be different and better.

This is what the current political moment feels like to me. There are days when the latest headlines feel so jarringly unprecedented that I find myself thinking, “Can this be happening? Can this be real?”

If you think these comparisons are a bit of a stretch, consider when “It’s a Wonderful Life” was made, and the frame of mind Capra was in when he made it.

Frank Capra, anti-fascist

In 1946, Capra was just returning to Hollywood filmmaking after serving for four years in the U.S. Army, where the Office of War Information had tasked him with producing a series of documentary films about World War II and the lead-up to it. Even though Capra hadn’t been on the front lines, he’d been immersed in the sounds and images of war for years on end, and he had become acutely familiar with Germany, Italy and Japan’s respective rises to fascism.

When deciding on his first postwar film, Capra recalled in his autobiography that he specifically “knew one thing – it would not be about war.” Instead, he chose to adapt a short story by Philip Van Doren Stern, “The Greatest Gift,” that Stern had originally sent to friends and family as a Christmas card in 1943.

Stern’s story is certainly not about war. But it’s not exactly about Christmas, either.

As Stern writes in his opening lines:

“The little town straggling up the hill was bright with colored Christmas lights. But George Pratt did not see them. He was leaning over the railing of the iron bridge, staring down moodily at the black water.”

The protagonist contemplates suicide because he’s “sick of everything” in the small-town “mudhole” he’s stuck in – until, that is, a “strange little man” gives him the chance to see what life would be like if he’d never been born.

It was Capra and his team of screenwriters who added the sinister Henry F. Potter to Stern’s short, simple tale. The Potter subplot encapsulates the film’s most trenchant, still-resonant themes: the unfairness of socioeconomic injustices; the pervasiveness of corporate and political corruption; the threat of monopolized power; the need for affordable housing.

These themes had, of course, run through many of Capra’s prewar films as well: “Mr. Deeds Goes to Town,” “You Can’t Take It with You” “"Meet John Doe” and “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,” the last of which also starred Jimmy Stewart.

But they take on a different kind of weight in “It’s a Wonderful Life” – a weight that’s especially visible on the weathered face of Stewart, who himself had just returned from a harrowing four-year tour of duty as a fighter pilot in Europe.

The idealistic vigor with which Stewart had fought crooked politicians and oligarchs as Mr. Smith is replaced by the bitterness, exhaustion, frustration and desperation with which he battles against Mr. Potter as George Bailey.

Life after Pottersville

By the time George has begged and pleaded his way out of Pottersville, the lost $8,000 is no longer top of mind. He’s mainly just relieved to find Bedford Falls as he had left it, warts and all.

And yet, the Bedford Falls that George returns to isn’t quite the same as the one he left behind.

In this Bedford Falls, the community rallies together to figure out a way to recoup George’s missing money. Their pre-digital version of a GoFundMe page saves George from what he’d feared most: bankruptcy, scandal and prison.

And even though his wife, Mary, tries to attribute this sudden wave of collectivist, activist energy to some sort of divine intervention – “George, it’s a miracle; it’s a miracle!” – Uncle Billy points out that it really came about through more earthly organizing means: “Mary did it, George; Mary did it! She told some people you were in trouble, and they scattered all over town collecting money!”

But the question of whether George actually wins his battle against Potter is a murky one.

While the typical Capra protagonist triumphs by defeating vice and exposing subterfuge, George never even realizes that Potter is the one who got hold of his money and tried to ruin his life. Potter is never held accountable for his crimes.

On the other hand, George is able to learn, from his time in Pottersville, what a crucial role he plays in his community. George’s victory over Potter, then, lies not in some grand final act of retribution, but in the incremental ways he has stood up to Potter throughout his life: not capitulating to Potter’s bullying or intimidation tactics; speaking truth to power; and running a community-centered business rather than one guided by greed and exploitation.

In recent months, there have been similar acts of protest, large and small, in the form of rallies, boycotts, immigrant aid efforts, subscription cancellations, food bank donations and more.

That doesn’t mean the U.S. has made it out of Pottersville, however.

Each day, more head-spinning headlines appear, whether they’re about masked agents terrorizing immigrant communities, the dismantling of anti-corruption oversights, the consolidation of executive power or the naked display of political grift.

Zuzu’s petals are still missing. Clarence still hasn’t gotten his wings.

But this holiday season, I’m hoping it will feel helpfully cathartic to go with George Bailey, for the umpteenth time, through the dark abyss of his dystopian nightmare – and come out with him, stronger and wiser, on the other side.

Nora Gilbert does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

As war in Ukraine enters a 5th year, will the ‘Putin consensus’ among Russians hold?

Polling in Russia suggests strong support for President Vladimir Putin. Yet below the surface, popular…

After a 32-hour shift in Pittsburgh, I realized EMTs should be napping on the job

A paramedic and university professor shares data about how strategic napping could help his own health…

How Dracula became a red-hot lover

Count Dracula was originally a rank-breathed predator. His transformation into a tragic romantic mirrors…