What’s the difference between ghosts and demons? Books, folklore and history reflect society’s super

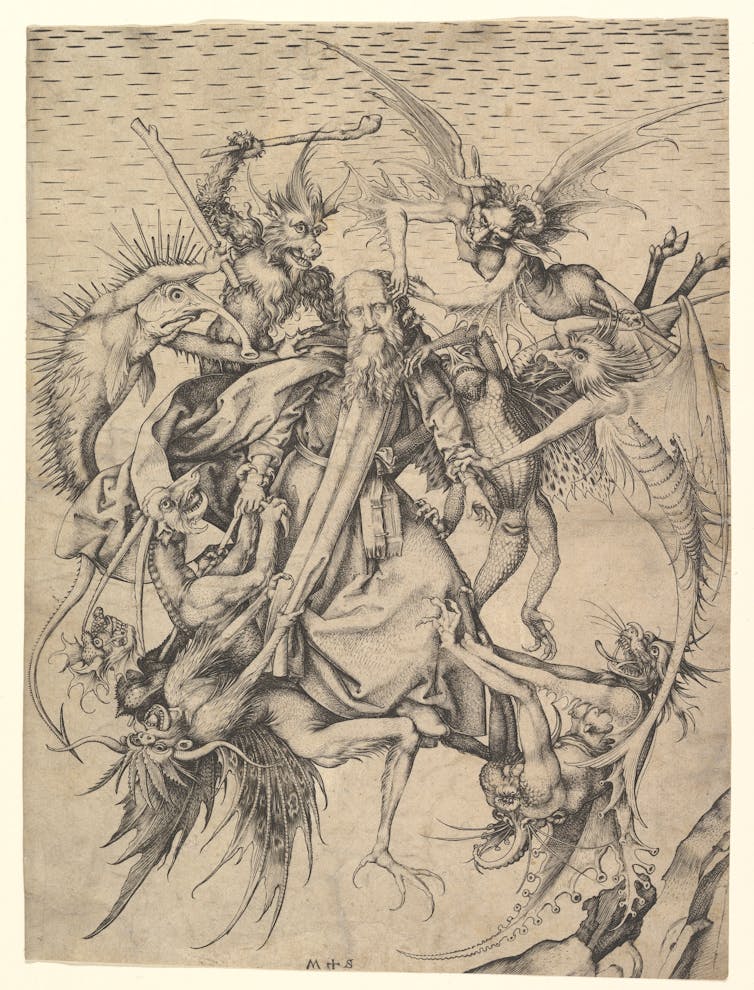

Artists often turn to the supernatural to reflect on and speak to the anxieties brought about by social, religious and political upheaval.

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

What’s the difference between ghosts and demons? – Landon W., age 15, The Colony, Texas

Belief in the spirit world is a key part of many faiths and religions. A 2023 survey of 26 countries revealed that about half the respondents believed in the existence of angels, demons, fairies and ghosts. In the United States, a 2020 poll found that about half of Americans believe ghosts and demons are real.

While the subject of demons and ghosts can inspire dread, the concepts themselves can be confusing: Is there a difference between the two?

Historically, communities have understood the supernatural according to their religious and spiritual traditions. For example, the terrifying ghosts of Pu Songling’s “Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio” operate differently than those haunting the works of William Shakespeare, even though both writers lived in the 17th century.

Literary representations of ghosts and demons often reflect the anxieties of communities experiencing social, religious or political upheaval. As a scholar of early modern English literature, my research focuses on how everyday people in 16th- and 17th-century Europe used storytelling to navigate major social changes. This era, often called the Renaissance, was punctuated by the establishment of mass media through printing, the global spread of colonization and the emergence of modern science and medicine.

Digging into the literary archive can reveal people’s ideas about demons and ghosts – and what made them different.

Martin Luther and the Reformation

On Oct. 31, 1517, Martin Luther, an ex-law student and former monk, boldly published his Ninety-Five Theses. In it, he rejected the Catholic Church’s promise that monetary payment to the church could reduce the amount of time one’s soul spent in purgatory. What began as a local protest in Wittenberg, Germany, soon swept all the major European powers into a life and death struggle over religious reform. Towns were besieged, landscapes scorched, villages pillaged.

This period, called the Reformation, led to the establishment of new Christian denominations. Among these Protestant churches’ early teachings was the edict that purgatory did not exist and souls could not return to Earth to haunt the living. Protestant reformers insisted that after death, one’s soul was immediately judged. The virtuous flew up to God in heaven; the sinful burned in hell with the Devil.

According to Protestants, ghosts were invented by Catholic priests to scare people into obedience. For example, the English translator of Ludwig Lavater’s 1572 book “Of Ghostes and Spirites Walking by Night” insists ghosts are the “falsehood of Monkes, or illusions of devils, franticke imaginations, or some other frivolous and vaine perswasions.” Should you ever encounter an “apparition,” you must call it out for what it truly is: a devil pretending to be a ghost.

Christopher Marlowe’s play “Doctor Faustus” comments on these debates. Written in the 1580s for a primarily Protestant audience, the play features a scene in which Dr. Faustus and his devil companion, Mephistopheles, trick the pope by snatching away his meal. A bewildered member of the papal court concludes “it may be some ghost … come to beg a pardon of your Holiness.” The audience knows full well, however, that these pranks are committed by the necromancer and his demon.

Ghostly haunting

In spite of Protestantism’s official stance against ghosts, belief in them persisted in the popular imagination.

Archival records show that ordinary people held fast to popular beliefs despite what their religious authorities decreed. For example, the casebook of Richard Napier, an astrological physician, reports several cases of “spirit” hauntings, including that of a young mother named Catherine Wells who had been “vexed … with a spirit” for three continuous years.

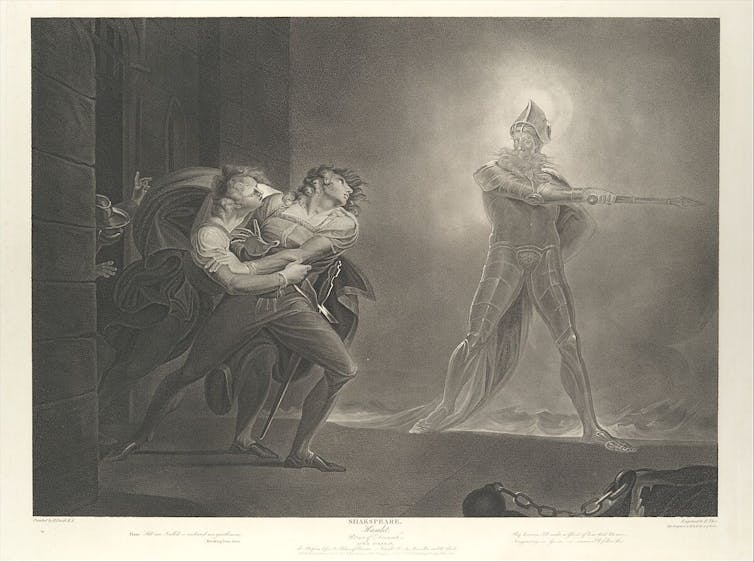

Popular plays provide additional evidence. Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” opens with a midnight visitation by the ghost of Hamlet’s father, telling his son he cannot rest in peace until his murderer is brought to justice. Ghostly victims seeking justice appear in other Shakespearean plays, including “Macbeth” and “Richard III.”

Cheap print, a form of common media, capitalized on the public’s interest in the paranormal. Part entertainment, part journalism, cheap print was read by all sorts of people. A 1662 pamphlet titled “A strange and wonderfull discovery of a horrid and cruel murther [murder]” describes Isabel Binnington’s unsettling encounter with the ghost of Robert Eliot. In her testimonial, she claims that Eliot’s ghost promised he would never hurt her. What he wanted was simply for her to hear his story: He had been murdered for his coins in the very house she occupied.

A 1730 broadside ballad called “The Suffolk Miracle” – still performed today – tells the tale of young lovers parted by an overprotective father. After the daughter is whisked away, her beloved dies of a broken heart. When his ghost later appears to her, she “joy’d to see her heart’s delight.”

Demonic possession

While reformed Protestant thinkers rejected the existence of ghosts, they enthusiastically accepted the reality of devils.

Reports of demonic possession were popular. Before his ascension to the English throne, King James VI of Scotland published a literary treatise on demonology in 1597. He argues that “assaultes of Sathan are most certainly practized” and “detestable slaves of the Devill” live among us.

The diaries of English Puritans offer further proof that beliefs about devilish encounters were common. In the 1650s, the Calvinist preacher Thomas Hall insisted that his godliness attracted the attention of Satan like a moth to a candle. From an early age, he complained, he was subjected to “Satanicall buffettings” and terrifying dreams. He believed, however, that surviving demonic temptation demonstrated his unwavering devotion to God.

Distinguishing ghosts from demons

Based on the literature, what can we conclude about how people saw ghosts and demons?

Early modern people often represented ghosts as sad and pitiable. They were depicted as the spiritual remainder of a recently deceased person, haunting their friends and kin – or, occasionally, a stranger. They retained some of their humanity and were psychically connected to a place, such as their former home, or to a person, such as their most cherished companion.

Demons, by contrast, were almost always malevolent tricksters who served the Devil. Demons lacked knowledge of what it meant to be human. Hell was the demons’ lair. Early modern texts describe them visiting the earthly plane to corrupt, possess or tempt humans to commit self-harm or violence against others.

Then and now, stories of ghosts and demons have provoked fear and wonder. Tales of the supernatural have inspired the imagination of kings, theologians, playwrights and everyday people.

Approaching the topic of the otherworldly with intellectual humility can inspire deeper curiosity about cultures across space and time. As Hamlet muses to his friend after meeting the ghost of his father, “There are more things in Heaven and Earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

Penelope Geng does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Why Stephen Colbert is right about the ‘equal time’ rule, despite warnings from the FCC

The ‘equal time’ rule has been around for a century and aims to promote broadcasters’ editorial…

As war in Ukraine enters a 5th year, will the ‘Putin consensus’ among Russians hold?

Polling in Russia suggests strong support for President Vladimir Putin. Yet below the surface, popular…

After a 32-hour shift in Pittsburgh, I realized EMTs should be napping on the job

A paramedic and university professor shares data about how strategic napping could help his own health…