Baseball returns to a Japanese American detention camp after a historic ball field was restored

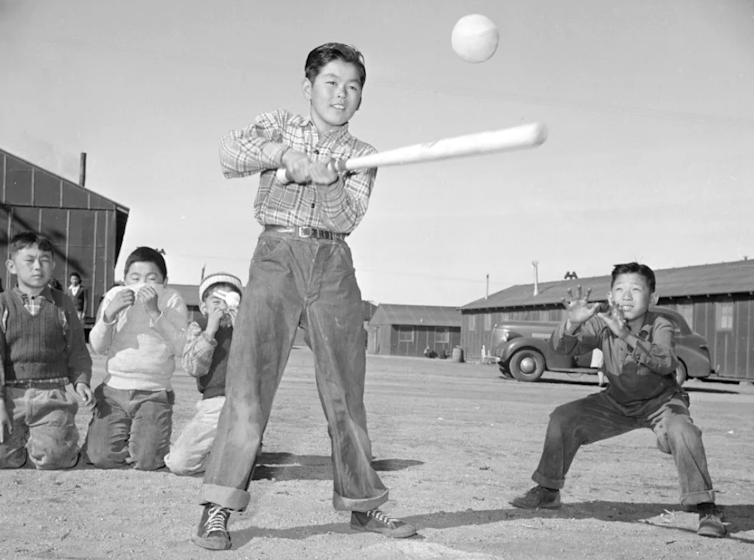

80 years after Japanese Americans were imprisoned at the Manzanar Relocation Center, descendants are returning to play the sport that gave prisoners hope and a sense of normalcy.

In the spring of 1942, 15-year-old Momo Nagano needed a way to fill her time.

She was imprisoned at the Manzanar Relocation Center along with approximately 10,000 other people of Japanese ancestry. When she’d arrived with her mother and two brothers, she’d been horrified.

The detention facility was located in the middle of the desert, about 225 miles northeast of Los Angeles. As I describe in my book “When Can We Go Back to America? Voices of Japanese American Incarceration during World War II,” barbed wire surrounded the perimeter and armed soldiers peered down from guard towers. The toilets and showers lacked partitions, and Nagano was forced to stand in long lines for hours in mess halls that served canned food. Her bed was a metal cot. She was directed to stuff straw into a bag for a makeshift mattress. She didn’t know whether she and her family would ever be able to return to their Los Angeles home.

One day, the teenager decided to pick up a glove and play softball. Her son, Dan Kwong, told me in an interview that Nagano ended up playing catcher for The Gremlins, one of the camp’s many women’s softball teams.

“In one game, a batter connected with the ball and then threw the bat, clocking my mom in the nose, breaking it,” he said. “But despite her injury, she still enjoyed playing, even though she didn’t think her team was very good.”

Eighty years later, the descendants of prisoners – such as Nagano’s son, Kwong – are playing baseball again in Manzanar. Thanks to an effort spearheaded by Kwong, a baseball field on the site has been restored as a way to both celebrate the resiliency of so many prisoners and memorialize this dark period in U.S. history.

A massive removal effort

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, the U.S. government wrongly assumed that Japanese-descended West Coast residents would be more loyal to Japan and presented an espionage risk.

So on Feb. 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued an executive order that gave the U.S. Army the authority to forcibly remove all first-generation immigrants from Japan and their American-born descendants from their West Coast homes.

In March 1942, U.S. soldiers began transporting the detainees to temporary detention sites under Army jurisdiction. The Manzanar site opened on March 21, 1942, and it eventually became one of 10 long-term detention centers, colloquially known as “the camps.”

According to Duncan Ryȗken Williams, the director of The Irei Project, which has compiled the most comprehensive list of those detained, nearly 127,000 people of Japanese ancestry were incarcerated between 1942 and 1947, when the last camp closed. Two-thirds of them were American citizens. Most were imprisoned for the duration of the war, and all were held without hearings or charges leveled against them.

A love of the game

Adjusting to their new grim reality, the detainees embraced the Japanese spirit of “gaman,” which means to endure hardship with dignity and resilience. They set up an education system and coordinated an array of activities. And they immediately organized baseball and softball games.

Many Japanese American families had already developed a passion for the two sports.

Horace Wilson, an educator from Maine, is credited with introducing baseball to Japan in the early 1870s. In 1872 the Yeddo Royal Japanese Troupe became the first Japanese people to play baseball on U.S. soil. When young Japanese men started immigrating to the U.S. in the late 19th century, they brought with them a love of America’s pastime.

Kerry Yo Nakagawa, the director of the Nisei Baseball Research Project, has written about the vanguards of Japanese American baseball. At a time when players of color were excluded from Major League Baseball, talented Japanese American ballplayers such as Kenichi Zenimura formed teams that barnstormed the country. They even played alongside Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig in an exhibition game in Fresno, Calif., on Oct. 29, 1927.

“Every pre-war Japanese American community had a baseball team and they brought their love of baseball with them to the assembly centers and their camps,” Nakagawa explained to me. Though Zenimura was forced to leave his Fresno home and go to a camp in Gila River, Arizona, he soon had a baseball diamond and a 32-team league up and running.

Patriotism on the diamond

At Manzanar, baseball was easily the most popular sport. According to Dave Goto, the Manzanar National Historic Site arborist, the camp had 10 baseball and softball diamonds on the grounds and more than 120 teams divided into 12 leagues. The camp newspaper, the Manzanar Free Press, provided detailed game recaps, and thousands turned out to watch the games at Manzanar’s “A” Field.

“Watching baseball played at a semi-pro level was entertainment and also gave them a sense of normalcy and community,” Nakagawa said.

But for those who felt their loyalty to the U.S. was unfairly questioned, baseball was also a powerful way to express their identity as Americans, especially for the U.S.-born children of Japanese immigrants. Takeo Suo, who was incarcerated at Manazarer, recalled, “Putting on a baseball uniform was like wearing the American flag.” Or, as Nakagawa put it, “What could be more American than playing the all-American pastime?”

After the war was over and the camps closed, those who’d been imprisoned had to focus on rebuilding their lives. Many were unable to return to their prewar hometowns. For those who ended up back on the West Coast, baseball continued to play an important role.

As Japanese American journalist and sports historian Chris Komai explained in a program at the Japanese American National Museum, “Baseball was a way for them to reestablish their communities while they dealt with antagonism and discrimination. Through the games they stayed connected with their friends and relatives who were now scattered.”

Postwar community baseball gave rise to the Southern California Nisei Athletic Union Baseball Leagues and other leagues that still operate. Kwong began playing for the Nisei Athletic Union in 1971 and does so to this day.

Rebuilding a dusty field of dreams

Nagano instilled in her son a commitment not only to baseball but also to social justice. A performance artist, Kwong stages a one-man play, “Return of the Samurai Centerfielder,” to shed light on this episode in history through the lens of playing baseball at Manzanar. Two years ago, he set out to restore the main Manzanar ball field and to bring baseball back to the site as a tribute to his late mother and other Manzanar detainees.

Working with Goto, the site arborist, volunteer construction supervisor Chris Siddons, Manzanar archaeologist Jeff Burton and other Manzanar site staff, Kwong and his team have restored the field almost exactly as it was. They carefully scrutinized archival photos, some taken by famed landscape photographer Ansel Adams and others snapped by studio photographer Toyo Miyatake, who’d been imprisoned at Manzanar. Miyatake’s photos were provided by his grandson, Alan Miyatake.

From November 2023 to October 2024, volunteers cleared sagebrush, dug post holes and poured concrete, enduring intense heat, strong winds and relentless dust.

On Oct. 26, 2024, baseball returned to Manzanar after more than 80 years before an invitation-only audience. In the inaugural game, Kwong’s Li’l Tokio Giants beat the Lodi JACL Templars. In the game that followed, players donned custom 1940s-style uniforms and used vintage baseball equipment lent by History For Hire prop house. Many of the players were descendants of Japanese Americans who’d been incarcerated at Manzanar and other camps.

That day, Kwong was emotional as he said, “Mom would have gotten such a kick out of this.”

Kwong’s team has completed an announcer’s booth in time for this year’s grand opening, a doubleheader open to the public. The games were originally scheduled for Oct. 18, 2025, but have been postponed due to the U.S. government shutdown.

For Kwong, staging a historical reenactment of how detainees played ball behind barbed wire pays tribute to their resilience, connects camp survivors and descendants with their past, and allows them to share their story with the American public. He hopes the games can become an annual event, a recurring celebration.

His motto: “In this place of sadness, injustice, and pain, we will do something joyous, righteous, and healing. We will play baseball.”

Susan H. Kamei is a researcher with The Irei Project and is a member of the Japanese American National Museum.

Read These Next

Why Stephen Colbert is right about the ‘equal time’ rule, despite warnings from the FCC

The ‘equal time’ rule has been around for a century and aims to promote broadcasters’ editorial…

After a 32-hour shift in Pittsburgh, I realized EMTs should be napping on the job

A paramedic and university professor shares data about how strategic napping could help his own health…

Enforcing Prohibition with a massive new federal force of poorly trained agents didn’t go so well in

Both Prohibition and current mass deportation efforts were hastily built, staffed by people permitted…