Zombies, jiangshi, draugrs, revenants − monster lore is filled with metaphors for public health

The ways in which zombies are spawned − and contained − reflect a range of public health principles.

Imagine a city street at dusk, silent save for the rising sound of a collective guttural moan. Suddenly, a horde of ragged, bloodied creatures appear, their feet shuffling along the pavement, their hollow eyes locked on fleeing figures ahead.

A classic movie monster, the zombie surged in popularity in the 21st century during a time of global anxiety – the Great Recession, the specter of climate change, the lingering trauma of the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the COVID-19 pandemic.

The zombie apocalypse became a way for people to explore the terrifying concept of societal collapse, a step removed from real threats such as nuclear war or global financial disaster.

As a public health epidemiologist and an amateur zombie historian, I couldn’t help but notice the striking parallels between what epidemiologists do to stop infectious disease outbreaks and what horror movie heroes do to stop zombies. The key questions posed in any zombie narrative – how did this start, how many are infected, how to contain it – are the identical questions that epidemiologists ask during a real infectious disease outbreak or pandemic.

In 2011, in fact, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published a zombie apocalypse preparedness guide that explained how readying oneself for a zombie apocalypse can prepare people for any large-scale disaster. The zombie is more than just a monster; it is a powerful, public health teaching tool.

Zombies in ancient history

The idea of the reanimated dead has been part of human history for millennia, showing up across cultures and long before modern germ theory or epidemiology existed. These creatures were often a way for societies to understand and explain the natural world and disease transmission in the absence of scientific knowledge.

The oldest written reference to creatures similar to modern zombies is found in “The Epic of Gilgamesh,” which was etched on stone tablets sometime between 2000 and 1100 B.C.E. Enraged after Gilgamesh rejects her marriage proposal, the goddess Ishtar tells him, “I shall bring up the dead to consume the living, I shall the make the dead outnumber the living.” This ancient terror – the dead overwhelming the living – has a direct parallel to the concept of an out-of-control epidemic in which the sick quickly overwhelm the healthy. Hollywood has readily adopted this concept in many zombie movies.

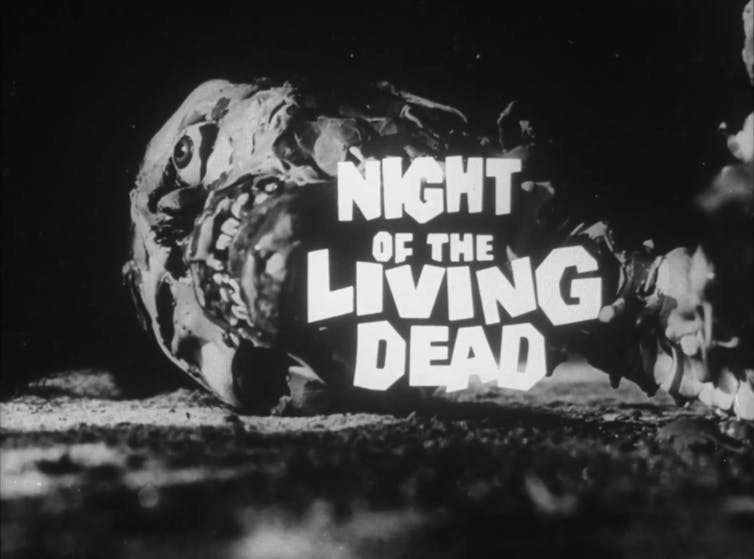

The origins of the flesh-eating corpse on screen date back to George Romero’s 1968 classic “The Night of the Living Dead.” You won’t hear the word “zombie” in Romero’s film, however – in the script, he called the creatures “flesh eaters.” Similarly, in Danny Boyle’s 2002 film “28 Days Later,” the terrifying creatures were called the “infected.” Both these terms, “flesh eaters” and “infected,” directly echo public health concerns – specifically, the spread of disease via a bacteria or virus and the need for quarantine to contain the afflicted.

The roots of the word zombie arefor the Haitian variety. thought to stretch back to West Africa and to words such as “nzambi,” which means “creator” in African Kongo, or “ndzumbi,” which means “corpse” in the Mitsogo language of Gabon. However, it was in Haitian Vodou, a religion that draws from the West African spiritual traditions among people who were enslaved on Haiti’s plantations, that the concept took its most terrifying form.

According to Vodou, when a person experiences an unnatural, early death, priests can capture and co-opt their soul. Slave owners capitalized on this belief to prevent suicide among the enslaved. To become a zombie – dead yet still a slave – was the ultimate nightmare. This cultural concept speaks not just to disease but to societal trauma and the public health crisis of forced labor.

Zombie-like creatures around the world

Across the globe, other reanimated corpses crop up in local folklore, often reflecting fears of improper burial, violent death or moral wickedness. Many tales about these eerie creatures don’t just convey how to avoid becoming one of them, but also detail how to stop or prevent them from taking over. This focus on prevention and control is at the heart of public health.

During the expansion of China’s Qing dynasty, which took place between 1644 and 1911, a creature known as the jiangshi, or “hopping zombie,” emerged amid widespread unrest and integration of non-Chinese minorities. The jiangshi were corpses suffering from rigor mortis and decomposition, reanimated when a soul couldn’t leave after a violent death. Instead of staggering, these mythological creatures would hop, and their method of attack was to steal a person’s lifeforce, or qi.

Fear of a lonely, restless afterlife led families who lost a loved one far from home to hire a Taoist priest to retrieve the body for proper burial with ancestors.

In Scandinavia, the draugr – meaning “again walker” or “ghost” – was a creature bent on revenge. According to lore, draugrs typically emerged from mean-spirited people or improperly buried corpses. Like zombies, they could turn regular people into draugrs by infecting them. They would attack their victims by devouring flesh, drinking blood or driving victims insane. Draugrs’ contagious nature is a model for disease transmission. What’s more, their seasonal activity – they most often appear at night in winter months – is similar to seasonal trends in infectious disease transmission.

In medieval times, meanwhile, legend had it that creatures called revenants – corpses that came out of their graves – stalked northern and western Europe. According to 12th-century English historian William of Newburgh, these creatures emerged from the lingering life force of people who had committed evil deeds during their lives or who experienced a sudden death. Clerics fueled people’s fears of becoming a revenant by claiming these creatures were created by Satan. The recommended but gruesome prevention method for this fate was to capture and dismember these creatures and to burn the body parts, especially the head.

Archaeological evidence from a medieval village in England suggests that communities heeded this advice. Archaeologists excavated the village’s burial grounds, and among human remains from the 11th to 13th centuries they found broken and burned bones with knife marks. They show how a community may have taken extreme measures to control a perceived contagion or threat to public safety, mirroring a modern-day quarantine or eradication protocols.

Perhaps the most striking similarity between these historical monsters and Hollywood zombies is that so many of them are created by an infectious agent of some kind. After an outbreak occurs, control is difficult to regain, underscoring the necessity of a rapid public health response.

Tom Duszynski does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Why Stephen Colbert is right about the ‘equal time’ rule, despite warnings from the FCC

The ‘equal time’ rule has been around for a century and aims to promote broadcasters’ editorial…

As war in Ukraine enters a 5th year, will the ‘Putin consensus’ among Russians hold?

Polling in Russia suggests strong support for President Vladimir Putin. Yet below the surface, popular…

Supreme Court rules against Trump’s emergency tariffs – but leaves key questions unanswered

The ruling strikes down most of the Trump administration’s current tariffs, with more limited options…