A white poet and a Sioux doctor fell in love after Wounded Knee – racism and sexism would drive them

Elaine Goodale and Charles Eastman’s 19th-century interracial marriage made them a media sensation. But tensions over gender, race and identity ultimately proved too hard to overcome.

Like many star-crossed lovers, Elaine Goodale and Charles Alexander Eastman came from different worlds.

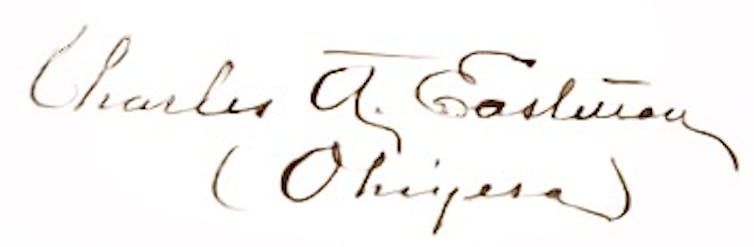

Goodale, born in 1863 to a family claiming Puritan roots, grew up on a farm in a remote part of western Massachusetts. In 1858, a baby first named Hakadah, later called Ohíye S’a, who then became widely known as Charles Alexander Eastman for most of his adult life, was born near Redwood Falls, Minnesota. A Wahpeton Santee Dakota, he fled to Manitoba, Canada, with tribal members during the 1862 Dakota War between the U.S. military and several bands of Dakota collectively known as the Santee Sioux.

In December 1890, the two unexpectedly met each other while working at the Pine Ridge Agency in the newly declared state of South Dakota. Even more improbably, they fell in love.

Just weeks later, booming Hotchkiss rifles 15 miles away signaled the start of the Wounded Knee Massacre. Federal troops ended up killing at least 250 Lakota Sioux men, women and children; the traumatic event, historian David Martínez writes, sparked “the abrupt transformation of Indian nations from geopolitical powers … to symbols of conquest.”

It also transformed Goodale and Eastman’s nascent relationship: They resolved to marry and to work together for Native American causes.

Wounded Knee, however, would also prove an unfortunate metaphor for their marriage.

In the research for my new dual biography, “Love and Loss After Wounded Knee: A Biography of an Extraordinary Interracial Marriage,” I dove into letters, photographs and hundreds of newspaper articles documenting this high-profile, late-19th-century relationship.

I came to understand that their marriage failed not only because of interpersonal tensions and a clash of values, but also because of some of the ways in which ideas about gender, race and Indigenous identity were rapidly changing in the U.S.

From writer to teacher

At 13, Goodale started publishing poetry in St. Nicholas Magazine, a popular children’s periodical. Her poems generated attention from the press, in addition to fan mail from notable men of letters, including Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. By the time she was 20, she had published five books.

But because poets without family fortunes needed other means to support themselves – and because women in the late 1800s had few career options – Goodale turned to teaching. She accepted a job at Virginia’s Hampton Institute, a boarding school that was founded to teach newly emancipated Black students. It later became part of the government’s program to assimilate Native Americans.

Goodale became convinced that Indigenous children would benefit more from schools in their own communities, rather than at government- or church-run boarding schools. She traveled to the Dakota Territory and opened a day school. She also turned from poetry to prose, documenting her observations of “Indian life and education” in dozens of articles.

By the time she came to Pine Ridge Agency, the administrative offices at the Oglala Lakota Indian Reservation, she had been appointed the first supervisor of education for the Dakotas.

The ideal ‘assimilated Indian’

Ohíye S’a’s early years were marked by family trauma and U.S. government policies aimed at seizing land and displacing and assimilating Native people. His mother died shortly after he was born, and during the Dakota War it was widely believed that his father and brothers had perished. His grandmother and uncle raised him until his mid-teenage years.

In 1873, the 15-year-old was surprised to discover that his father was, in fact, alive. Jacob Eastman had taken a European-American name and converted to Christianity. He was convinced that only a formal English-language education could provide a path forward for Native people.

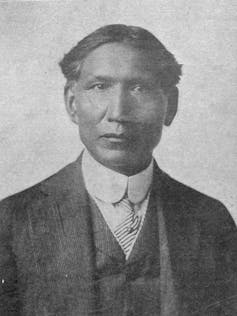

At his father’s urging, Ohíye S’a became “Charles Eastman,” and he also converted to Christianity. He attended a series of boarding schools before landing at Dartmouth College and then Boston University Medical School.

His white mentors saw Eastman – the only Native person in his class at either institution – as the ideal “assimilated Indian.” His achievements often appeared in newspapers with headlines like “He’s a Winner: Sioux Indian Who Got a Boston University Degree,” an allusion to the fact that “Ohíye S’a” translated to “winner.”

It isn’t clear whether Eastman ever thought of himself in that way. But throughout his life, he straddled the world in which he was raised and the one in which he was educated. His first job, as agency physician at Pine Ridge, placed him at the nexus of these two cultures.

An unlikely pair, a media sensation

After the shots rang out near Wounded Knee Creek, Eastman’s medical education was put to the test. Called into service as a nurse, Goodale also tended the wounded and dying in the makeshift hospital at a nearby church.

Six months later, Elaine and Charles were married in New York City in June 1891, much to the consternation of her family.

The couple’s nuptials appeared in hundreds of newspapers, partially due to the rarity of an interracial marriage in the 19th century. Much of the coverage was rife with racist stereotypes.

The Watertown Times in New York proclaimed, “Poetess Marries a Big Injun’”; the San Francisco Examiner ran a front-page story declaring “Fair Bride of An Indian: Elaine Goodale Weds the Red Man of Her Choice.”

Sometimes, articles focused on Charles’ educational background, often misrepresenting it by suggesting he had attended Cornell, Harvard or Yale. He was referred to as a “specimen,” with racialized language discussing his physical attributes: “He is of medium height … with all the peculiarities of his people in his features. His eyes are small and glittering, his face and nose are broad and his cheek bones very pronounced,” according to the San Francisco Examiner.

This type of media coverage – highlighting the differences between Elaine and Charles’ backgrounds, while pointedly describing Charles in stereotyped ways – would dog them throughout their marriage.

Professional travails, personal problems

Charles attempted to set up his own medical practice in St. Paul, Minnesota. But white patients proved reluctant to see “an Indian doctor,” while Native patients were hesitant to patronize a physician dispensing unfamiliar medicines. The practice failed.

Financial pressures increased over the next decade as Elaine and Charles became parents of six children. They moved frequently: Charles took on a series of jobs, including recruiting for the YMCA, lobbying on behalf of the Santee Sioux, and working as an “outing agent” at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, which involved finding summer placements for Native students with white families in a further attempt to Americanize them.

Because Charles left behind few personal papers, it’s difficult to know if he believed in this program. But it’s easy to see how it could have created an identity crisis of sorts.

At other points in his life, Charles seemed to put his Dakota identity front and center. For example, he was one of the co-founders of the Society of American Indians, an organization that worked on behalf of self-determination for Native Americans. He even served as its president in 1918. Meanwhile, his wife remained a staunch believer in assimilation.

At Elaine’s urging – and likely, under her editorial stewardship – Charles began publishing stories and then books about his “Indian Boyhood.” While Elaine continued writing and was able to publish a few books, his literary career took off and hers stalled out.

Even their children weren’t spared from the headlines. An article in the St. Paul Globe wrote, of one of the Eastman children, “… the child had not inherited any of the attractiveness of the mother. It was a veritable old squaw miniature.”

In her personal writing, Elaine never acknowledged her children as biracial. The public stereotyping and private dismissal of the Eastman children’s identities were undoubtedly another stressor in an already-stressed marriage.

Pictures worth a thousand words

After many moves, the Eastmans landed in Amherst, Massachusetts. But Charles did not stay put, embarking upon a vigorous new career on the lecture circuit.

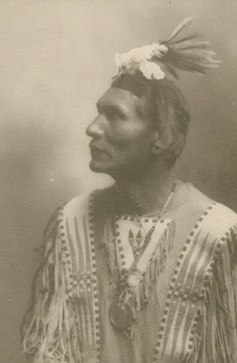

He became one of the best-known Native Americans of his era, as well as one of the most photographed.

Sometimes Charles chose to appear in a Victorian suit and cravat. Other times he posed in traditional Sioux regalia. Often the coverage of his talks focused more on what he was wearing than the content of his lecture. Historian Kiara Vigil suggests that Charles knew that his dress functioned as an advertisement for his work, arguing that his choice of attire was strategic: “Eastman’s ability to dress up as an Indian, or not, enabled him to address diverse audiences and their expectations.”

He was away from home more than he was present, further fueling Elaine’s resentment. In personal letters, she described her bitterness at Charles leaving the children and household to her sole care, and her belief that he was reinforcing the gender roles she’d railed against. While she certainly understood that his posing in buckskin and feathered headdress was good marketing, she probably never realized what reclaiming his Indigenous identity meant to Charles; she, too, thought of him as the product of successful assimilation.

It all falls apart

The personal and professional pressures on the Eastmans continued through the early years of the 20th century.

They reached a breaking point after their second daughter, Irene Taluta, died in the 1918 influenza pandemic. The tragic loss of a beloved child continued to unravel an already frayed marriage.

Elaine and Charles separated in 1921, though they never formally divorced.

I’ve been interested in the Eastmans and their unlikely marriage since I first learned of it years ago. As I pieced together parts of this complex relationship, I became convinced that while their compelling story reveals much about late 19th and early 20th century America, it’s also a story for today.

At a time of profoundly unsettling controversies around race, immigration and identity, the marriage of Elaine Goodale and Charles Eastman underscores why it can be so challenging for people from different backgrounds to truly understand each other.

But their story – how their mutual commitment to improve life for Native American people brought them together, how their quest to educate the nation about a marginalized people gave them purpose, and the ways in which they melded the personal and the political – also suggests the importance of trying.

Julie Dobrow does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Trump says climate change doesn’t endanger public health – evidence shows it does, from extreme heat

Climate change is making people sicker and more vulnerable to disease. Erasing the federal endangerment…

Citizenship voting requirement in SAVE America Act has no basis in the Constitution – and ignores pr

The House has passed a bill to require proof of citizenship for voting. Although it likely won’t become…

Polymers from earth can make cement more climate-friendly

Cement is responsible for about 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and demand is growing as the…