Is there any hope for the internet?

The author of the new book ‘Attention and Alienation’ wonders if the online world can ever become a place where kindness and human flourishing are the prevailing ethos.

In 2001, social theorist bell hooks warned about the dangers of a loveless zeitgeist. In “All About Love: New Visions,” she lamented “the lack of an ongoing public discussion … about the practice of love in our culture and in our lives.”

Back then, the internet was at a crossroads. The dot-com crash had bankrupted many early internet companies, and people wondered if the technology was long for this world.

The doubts were unfounded. In only a few decades, the internet has merged with our bodies as smartphones and mined our personalities via algorithms that know us more intimately than some of our closest friends. It has even constructed a secondary social world.

Yet as the internet has become more integrated in our daily lives, few would describe it as a place of love, compassion and cooperation. Study after study describe how social media platforms promote alienation and disconnection – in part because many algorithms reward behaviors like trolling, cyberbullying and outrage.

Is the internet’s place in human history cemented as a harbinger of despair? Or is there still hope for an internet that supports collective flourishing?

Algorithms and alienation

I explore these questions in my new book, “Attention and Alienation.”

In it, I explain how social media companies’ profits depend on users investing their time, creativity and emotions. Whether it’s spending hours filming content for TikTok or a few minutes crafting a thoughtful Reddit comment, participating on these platforms takes work. And it can be exhausting.

Even passive engagement – like scrolling through feeds and “lurking” in forums – consumes time. It might feel like free entertainment – until people recognize they are the product, with their data being harvested and their emotions being manipulated.

Blogger, journalist and science fiction writer Cory Doctorow coined the term “enshittification” to describe how experiences on online platforms gradually deteriorate as companies increasingly exploit users’ data and tweak their algorithms to maximize profits.

For these reasons, much of people’s time spent online involves dealing with toxic interactions or mindlessly doomscrolling, immersed in dopamine-driven feedback loops.

This cycle is neither an accident nor a novel insight. Hate and mental illness fester in this culture because love and healing seem to be incompatible with profits.

Care hiding in plain sight

In his 2009 book “Envisioning Real Utopias,” the late sociologist Erik Olin Wright discusses places in the world that prioritize cooperation, care and egalitarianism.

Wright mainly focused on offline systems like worker-owned cooperatives. But one of his examples lived on the internet: Wikipedia. He argued that Wikipedia demonstrates the ethos “from each according to ability, to each according to need” – a utopian ideal popularized by Karl Marx.

Wikipedia still thrives as a nonprofit, volunteer-ran bureaucracy. The website is a form of media that is deeply social, in the literal sense: People voluntarily curate and share knowledge, collectively and democratically, for free. Unlike social media, the rewards are only collective.

There are no visible likes, comments or rage emojis for participants to hoard and chase. Nobody loses and everyone wins, including the vast majority of people who use Wikipedia without contributing work or money to keep it operational.

Building a new digital world

Wikipedia is evidence of care, cooperation and love hiding in plain sight.

In recent years, there have been more efforts to create nonprofit apps and websites that are committed to protecting user data. Popular examples include Signal, a free and open source instant messaging service, and Proton Mail, an encrypted email service.

These are all laudable developments. But how can the internet actively promote collective flourishing?

In “Viral Justice: How We Grow the World We Want,” sociologist Ruha Benjamin points to a way forward. She tells the story of Black TikTok creators who led a successful cultural labor strike in 2021. Many viral TikTok dances had originally been created by Black artists, whose accounts, they claimed, were suppressed by a biased algorithm that favored white influencers.

TikTok responded to the viral #BlackTikTokStrike movement by formally apologizing and making commitments to better represent and compensate the work of Black creators. These creators demonstrated how social media engagement is work – and that workers have the power to demand equitable conditions and fair pay.

This landmark strike showed how anyone who uses social media companies that profit off the work, emotions and personal data of their users – whether it’s TikTok, X, Facebook, Instagram or Reddit – can become organized.

Meanwhile, there are organizations devoted to designing an internet that promotes collective flourishing. Sociologist Firuzeh Shokooh Valle provides examples of worker-owned technology cooperatives in her 2023 book, “In Defense of Solidarity and Pleasure: Feminist Technopolitics in the Global South.” She highlights the Sulá Batsú co-op in Costa Rica, which promotes policies that seek to break the stranglehold that negativity and exploitation have over internet culture.

“Digital spaces are increasingly powered by hate and discrimination,” the group writes, adding that it hopes to create an online world where “women and people of diverse sexualities and genders are able to access and enjoy a free and open internet to exercise agency and autonomy, build collective power, strengthen movements, and transform power relations.”

In Los Angeles, there’s Chani, Inc., a technology company that describes itself as “proudly” not funded by venture capitalists. The Chani app blends mindfulness practices and astrology with the goal of simply helping people. The app is not designed for compulsive user engagement, the company never sells user data, and there are no comments sections.

No comments

What would social media look like if Wikipedia were the norm instead of an exception?

To me, a big problem in internet culture is the way people’s humanity is obscured. People are free to speak their minds in text-based public discussion forums, but the words aren’t always attached to someone’s identity. Real people hide behind the anonymity of user names. It isn’t true human interaction.

In “Attention and Alienation,” I argue that the ability to meet and interact with others online as fully realized, three-dimensional human beings would go a long way toward creating a more empathetic, cooperative internet.

When I was 8 years old, my parents lived abroad for work. Sometimes we talked on the phone. Often I would cry late into the night, praying for the ability to “see them through the phone.” It felt like a miraculous possibility – like magic.

I told this story to my students in a moment of shared vulnerability. This was in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, so the class was taking place over videoconferencing. In these online classes, one person talked at a time. Others listened.

It wasn’t perfect, but I think a better internet would promote this form of discussion – people getting together from across the world to share the fullness of their humanity.

Efforts like Clubhouse have tapped into this vision by creating voice-based discussion forums. The company, however, has been criticized for predatory data privacy policies.

What if the next iteration of public social media platforms could build on Clubhouse? What if they brought people together and showcased not just their voices, but also live video feeds of their faces without harvesting their data or promoting conflict and outrage?

Raised eyebrows. Grins. Frowns. They’re what make humans distinct from increasingly sophisticated large language models and artificial intelligence chatbots like ChatGPT.

After all, is anything you can’t say while looking at another human being in the eye worth saying in the first place?

Aarushi Bhandari does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

What is and isn’t new about US bishops’ criticism of Trump’s foreign policy

The Catholic Church’s teachings on ‘just war’ have guided leaders’ long history of opposing…

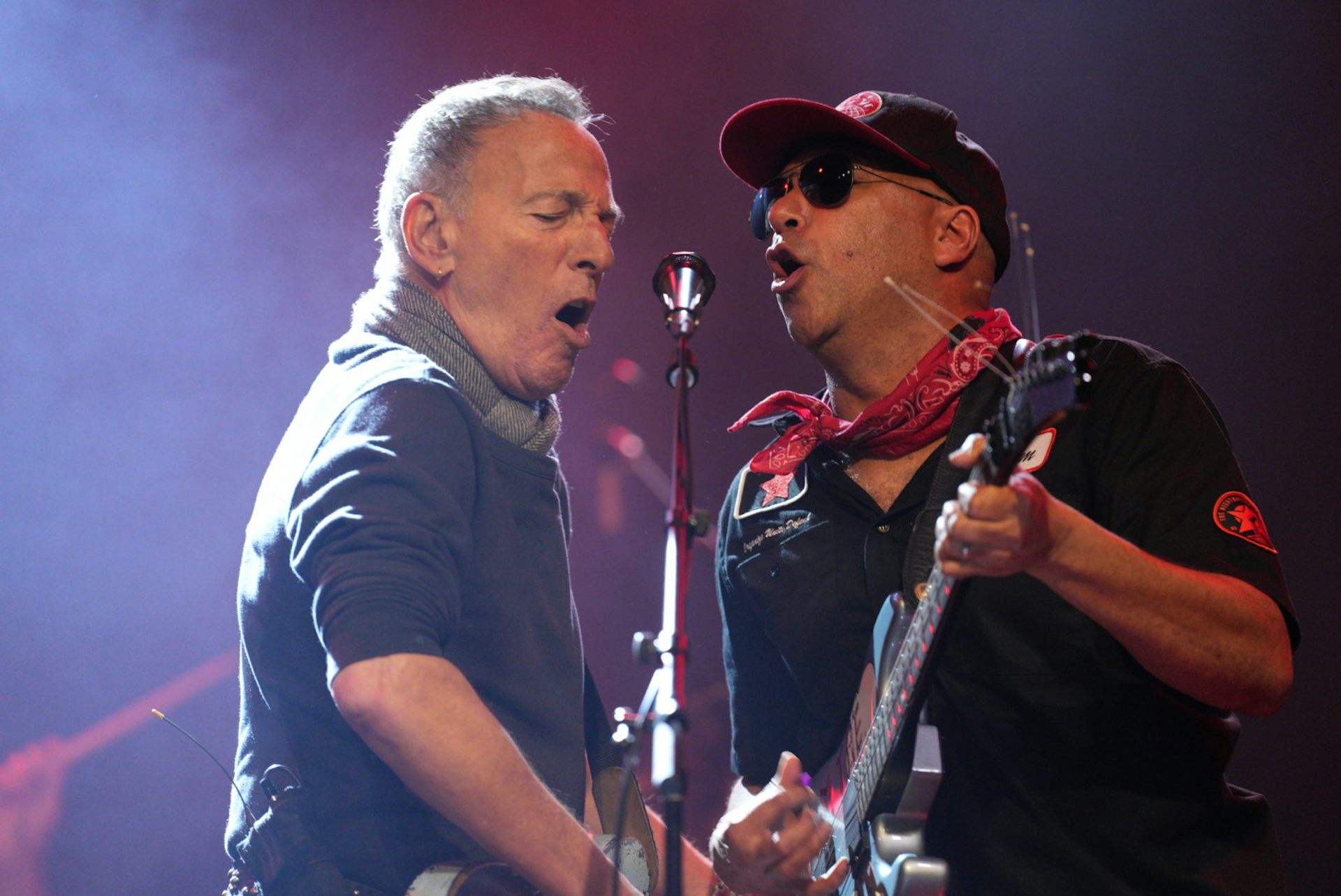

‘Which Side Are You On?’: American protest songs have emboldened social movements for generations, f

Bruce Springsteen wrote and recorded ‘Streets of Minneapolis’ within days of Alex Pretti’s killing,…

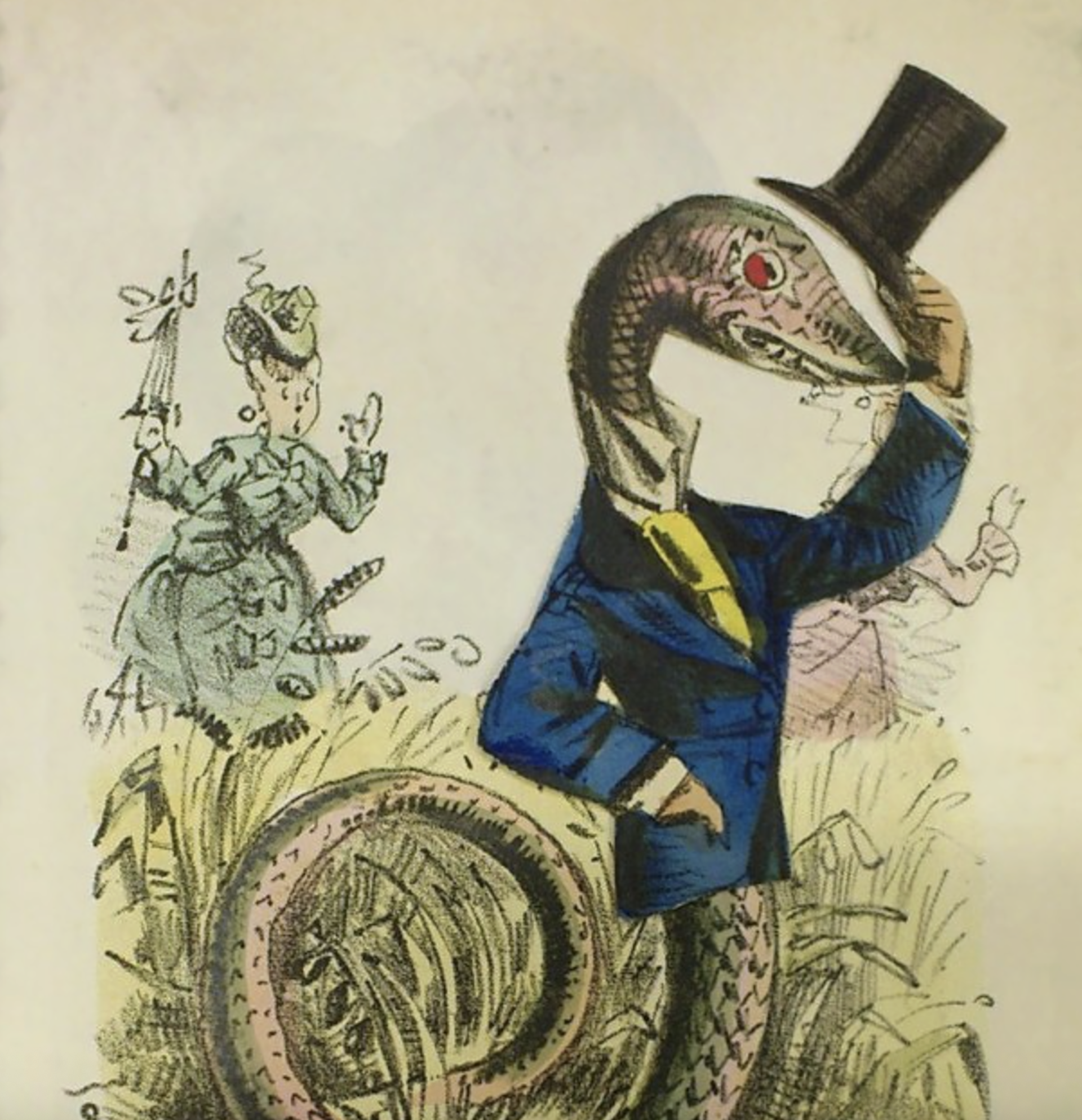

Valentine’s Day cards too sugary sweet for you? Return to the 19th-century custom of the spicy ‘vine

Victorians found a way to anonymously tell people they didn’t like exactly how they felt.