A new book of Edward Gorey’s drawings shows what’s lost when the artist’s sexuality is glossed over

‘Queer’ is a word often used to describe Edward Gorey’s mysterious, spooky art. So why is it so hard to acknowledge the artist behind them was queer as well?

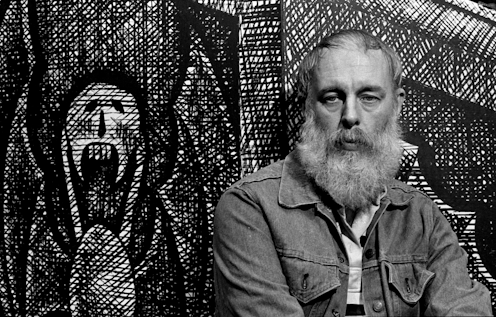

Artist, illustrator and writer Edward Gorey would have turned 100 this year, and the recently published “From Ted to Tom: The Illustrated Envelopes of Edward Gorey” is a fitting celebration of his wit and talent.

The book reproduces, in stunning detail, a series of 50 elaborately illustrated envelopes Gorey created in the mid-1970s. But when I started reading “From Ted to Tom,” I felt confused – and a little let down.

The book makes no mention of Gorey’s queerness. To me, this is a missed opportunity to shed light on how being gay may have fueled some of his most personal work.

The master of macabre

Today, Edward Gorey is widely known for his sprawling, macabre-yet-humorous body of work, which spans nearly every medium.

There are dozens of his own books, notably “The Doubtful Guest” and “The Gashlycrumb Tinies,” as well as cover designs for many others; sets and costumes for the 1977 Tony Award-winning revival of Bram Stoker’s “Dracula”; the opening credit sequence for the PBS television series “Mystery!”; “The Fantod Pack,” a deck of Tarot-like cards; and hand-sewn, surrealist dolls.

His stories often feature adults and children alike who meet untimely ends through mostly hilarious, unlikely accidents – and, yes, the occasional straight-up murder. But they’re never gratuitous, nor do they glorify violence for violence’s sake.

As for his personal life, Gorey may have been what today we’d call asexual; Gorey himself used the term “undersexed,” but he also acknowledged, when asked directly about his sexuality, that he “supposed” he was gay.

Mark Dery’s 2018 Gorey biography, “Born to be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey,” documents the artist’s participation in postwar gay life. The book details a handful of crushes Gorey had on various men, at least one of which – a brief affair with a man named Victor – involved some physical intimacy.

To whatever extent Gorey entertained sex or romance, it was with men. As Dery points out, however, this fact largely goes unaddressed in discussions of the artist’s work.

A chance encounter

“From Ted to Tom” reinforces this silence.

The “Tom” is Tom Fitzharris, the author of the book’s introduction and some commentary at the book’s end.

In the introduction, Fitzharris explains that before he met Gorey, he was already collecting the artist’s “small, exquisite books.”

After attending a gallery exhibit of Gorey’s work in 1974, Fitzharris mailed him one of the books from his collection to request Gorey’s signature, along with a cryptic inquiry about two of the book’s characters. Gorey obliged and returned the book with a similarly cryptic reply.

Soon after this exchange, Fitzharris spotted Gorey on the street and introduced himself. The two soon began meeting regularly “for dinner, the theater, coffee, and especially the ballet, his great passion,” one that Fitzharris shared. When Gorey left to summer on Cape Cod, he began sending Fitzharris the envelopes collected in “From Ted to Tom.”

Fitzharris shares almost no information about himself in the book, and he has never commented publicly about his own sexuality. However, even his dry, minimalist narration cannot conceal the intensity of their connection.

Describing his first visit to Gorey’s apartment, he writes: “I thought I’d be at Gorey’s for ten minutes, but I left two hours later.” Whether Fitzharris lost track of time as the two explored their “dozens of shared interests” or simply couldn’t tear himself away, when he finally made it back to work, he was surprised that he still had a job.

The envelope as canvas

Given this voracious drive to create, it is no surprise that Gorey saw an object as humble as a letter envelope as a creative opportunity. As Dery points out, Gorey was also making his illustrated envelopes as the mail art movement was becoming popular. Sparked by artist Ray Johnson in the 1960s – who, like Gorey, lived in New York City – it involved artists using the postal service to exchange works of art, using it as an alternative to the commercial galleries and museums that artists had largely depended on.

The 50 envelopes reproduced in “From Ted to Tom” was not Gorey’s first dalliance with the envelope as canvas; he’d experimented with it six years earlier, while in the midst of a collaboration with author and editor Peter Neumeyer, with whom he produced three children’s books.

In his drawings to Neumeyer, Gorey mostly seems to be having fun playing around with a new formal challenge: how to integrate drawings with the prerequisite address text in a satisfying way.

Because I study how people use images to make sense of the world, I couldn’t help but notice key differences between the Neumeyer envelopes and those that Gorey sent to Fitzharris.

The Fitzharris series is poised and polished from the jump. Gorey’s distinctive hand-lettering is crisp, precise and perfectly straight, each envelope a complete scene. Some scenes are more complex than others, but each is a complete thought.

There’s another notable difference between the Neumeyer and Fitzharris envelopes. While the former features a revolving cast of real and imaginary creatures, the latter has two co-stars: two black-and-white dogs, sides emblazoned with matching, serifed T’s.

In his introduction to the book, Fitzharris confirms that the animals represent Gorey and him. Fitzharris is also clearly more than the lucky witness to a burst of creative genius. He is its muse.

‘Pen pal’ or something more?

Whatever Gorey’s artistic ambitions for the project, it is also a visual diary of sorts: an album of their shared experiences, their common interests and hobbies, and a document of Gorey’s goings-on while they were apart.

Take, for example, an envelope that depicts the canine duo standing amid a vast assemblage of blue bottles, with Fitzharris’ address displayed as labels.

“All the blue bottles are a recollection of a window full of them in one of the antique shops I stopped in after you left that Sunday,” Gorey wrote in the accompanying letter. “The sun coming through them is not reproducible, at least by me.”

In the same letter, Gorey struggles to convey the depth of his feeling upon receiving a recent letter from Fitzharris.

“I used to maintain that if it couldn’t be put into words it didn’t exist; if anything I believe rather the opposite now. All of which is rather a strangled attempt to say that I appreciated your letter of the 23rd very much, but that I don’t know how to say so directly. Yes.”

What did Fitzharris’ letter say that moved Gorey so much? What is the meaning of his singular, elliptical “yes”? Is it simply stylistic? Or is it a response?

We’ll likely never know. But evidently whatever Fitzharris said moved him deeply.

There are other poignant scenes. In his notes to “From Ted to Tom,” Fitzharris takes credit for introducing Gorey to the French phrase “heure bleue,” which translates to “the blue hour” and refers to the time of day just after the sun sets. Gorey’s delight is reflected in a lovely scene of quiet companionship.

Tom and Ted stand at a low fence or porch railing, sharing drinks and gazing up at a darkening sky as dusk settles over thick foliage. For once leaving nothing to the imagination, he inscribes “HEURE BLEUE” next to the image in thick, bold letters – a rare act of captioning.

This unusual relative directness continues into the accompanying letter. Though he can hardly bear admitting it, Gorey describes their recent visit as “a happy day,” immediately qualifying the comment as a “revolting phrase.”

One “cannot help but think how seldom in life one knows one is having one at the time,” he continues. The phrasing is somewhat innocuous. But I wonder how much pleasure Gorey must have felt – and how strong his need to convey it must have been – to overcome the force of his “revulsion.”

This push and pull between attraction to one another and repulsion at one’s own spontaneous emotion supplies the dynamism that make the drawings in “From Ted to Tom” so compelling.

Despite this powerful current, Fitzharris, who is credited as the book’s editor, leaves the topic of Gorey’s sexuality untouched in both his introduction to the book and its end notes, where he provides a guide to some of the personal and cultural references in Gorey’s drawings and letters. The book’s back cover refers to Fitzharris as the artist’s “pen pal.”

Denied access to the underlying details driving this dynamism, the reader loses the chance to reflect on the source of this electrical current, its impact on his art, and how Gorey’s struggles with intimacy and desire, which are all too universal, were also undoubtedly shaped by the challenge of being gay in a deeply homophobic society.

Rather than limiting the understanding of his work, accounting for Gorey’s queerness invites viewers of his art and readers of his work into deeper communion with the artist – and themselves.

Elizabeth Wolfson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

How a largely forgotten Supreme Court case can help prevent an executive branch takeover of federal

An FBI raid on a Georgia elections facility has sparked concern about Trump administration interference…

Do special election results spell doom for Republicans in 2026?

Special election results have anticipated recent midterm outcomes. With Democrats now overperforming,…

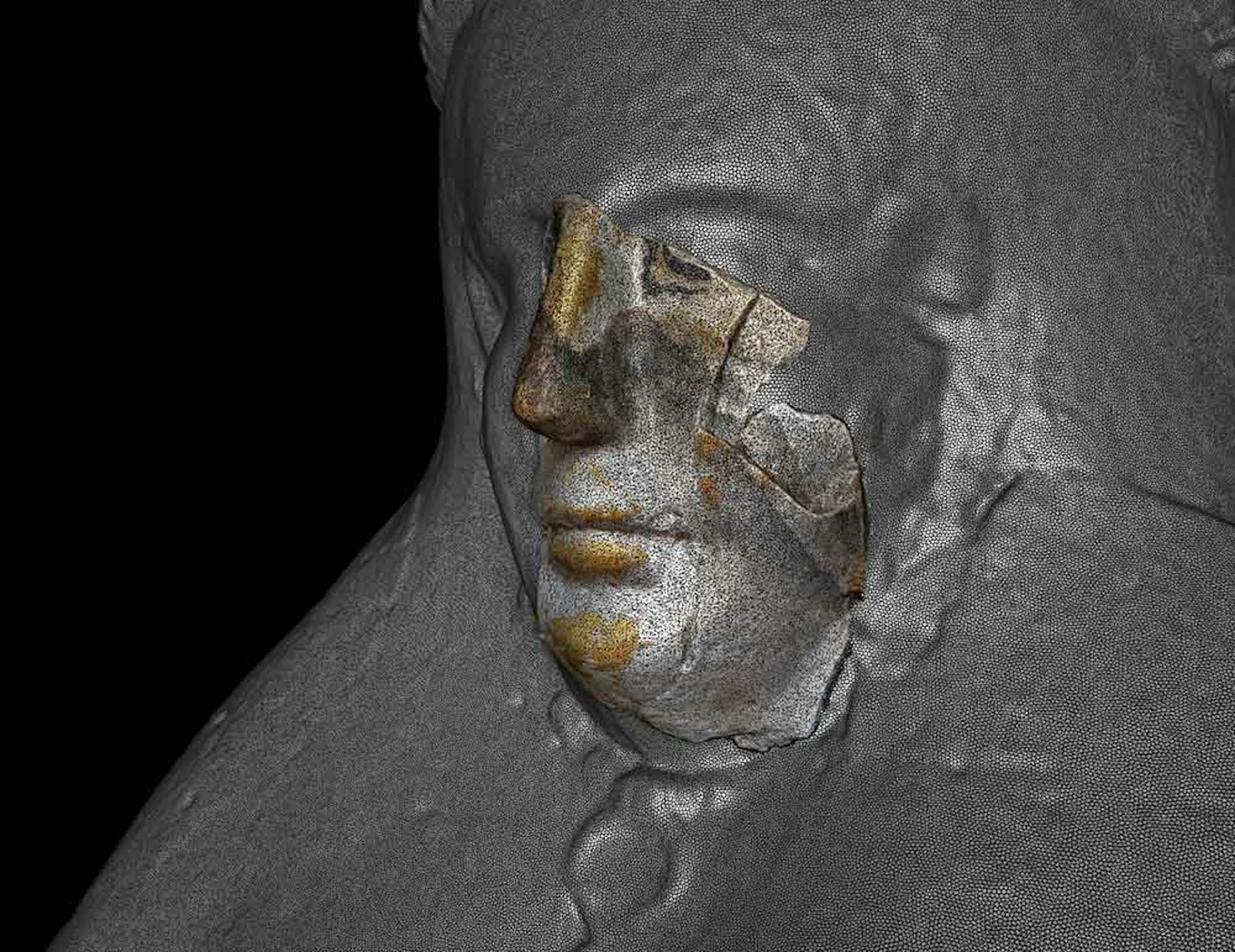

3D scanning and shape analysis help archaeologists connect objects across space and time to recover

Digital tools allow archaeologists to identify similarities between fragments and artifacts and potentially…