What James Earl Jones can teach us about the activism of art in times of crisis

In the heat of the Civil Rights Movement, Jones didn’t give rousing speeches or lead marches. Instead, he doubled down on his art.

The death of James Earl Jones has forced me to consider the end of an era.

Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier and Jones were giants in my industry. They were Black performers whose ascents to stardom occurred in the tumultuous 1960s, when I was an infant. All three were politically active, although each operated in a significantly different way.

In 1967, there were more than 150 riots fueled by racial tensions in U.S. cities. Many Americans worried that the nation would implode over racial conflict, and President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed the Kerner Commission to study the sources of racial turmoil.

At the time, Jones was an actor of growing renown on television and the theatrical stage. He had performed in “Danton’s Death” on Broadway and was featured on NBC’s “Tarzan,” among other projects.

Jones found himself grappling with a question that has roiled many artists, then and now: In troubling times, what is an artist to do?

He didn’t give rousing speeches, as Belafonte did. Nor did he hand-deliver cash to student activists in Mississippi during the Freedom Summer, as Poitier had done.

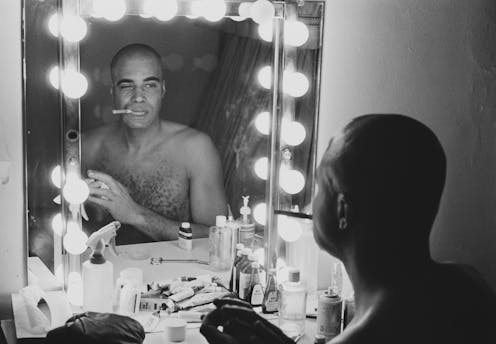

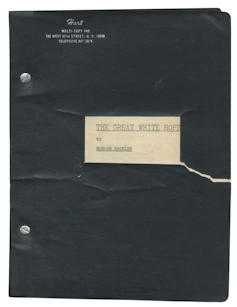

Instead, Jones decided to work on a play about a boxer, “The Great White Hope,” which had been written by Howard Sackler at Arena Stage, a Washington-based theater company in the growing regional theater movement.

Embodying Black power

While cities were burning all over America, why would an actor hoping to make a difference sign on to play a boxer? If they aren’t willing to put their life on the line, shouldn’t they at least work on a play about the Civil Rights Movement, racism or police brutality?

However, “The Great White Hope” wasn’t a simple, sentimental sports drama. Sackler based the play’s protagonist, Jack Jefferson, on boxer Jack Johnson, who became the first Black heavyweight champion in 1908.

African Americans riotously celebrated Johnson, who had captured the title just 45 years after the Emancipation Proclamation. In the face of virulent Jim Crow racism, Johnson stood as a man who, if given a fair shot, could beat anyone.

In his book “A Beautiful Pageant: African American Theatre, Drama and Performance in the Harlem Renaissance, 1910-1927,” theater historian David Krasner argues that Johnson’s victory was one of the key events that fueled the Harlem Renaissance, the Black intellectual and cultural movement that birthed jazz music, the poetry of Langston Hughes, the writings of Zora Neale Hurston and the sculptures of Augusta Savage.

The confidence Johnson inspired was contagious: If a Black man could handily beat a white man in a boxing ring, there was no reason Black artists and writers couldn’t fashion groundbreaking works, plumbing their lives and their histories – as Hurston did – to become champions of Black culture.

The play is written in three acts, and it follows Jefferson and his fictional white lover, Eleanor Bachman, from 1908 to 1915. After Jefferson wins the title, the government hounds the couple, in part because of their interracial romance. Officials eventually detain them as they enter Ohio under the Mann Act, a law ostensibly enacted to halt prostitution but often used to intimidate interracial couples. The government tells Jefferson that it will drop the charges if he’s willing to throw a fight to an inferior white boxer.

Jones won a Tony Award for his portrayal of a Black man possessed with talent, confidence and strength, whose biggest problem was that he simply refused to stay in his lane.

A different kind of fighter

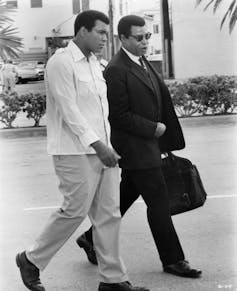

Boxer Muhammad Ali was also a big fan of Jones’ performance.

Ali had been stripped of his heavyweight title in 1967 because he was a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War, refusing to enlist after being drafted. When Ali saw “The Great White Hope,” he felt like he was looking in the mirror.

“You just change the time, date and the details and it’s about me!” Life magazine quoted him saying.

It’s strange to think about how historical events can be distilled into emotions like fear, love, jealousy and righteousness. But James Earl Jones was somehow able to hold a Black boxer who loved a white woman in conversation with someone unable to bring himself to fight in Vietnam.

Jones probably knew that a performance on a stage seen by a few thousand people would do little to end the Vietnam War, racial inequality or police brutality.

But I think Jones was looking to change the culture. He was trying to change the country’s understanding of what it means to fight – and what a freedom fighter is.

Is a fighter someone who knocks out their opponent? Or someone who follows their heart? Is a fighter someone who takes up arms at the behest of their government? Or is a fighter someone who’s willing to risk their livelihood for their values?

Sometimes, activism can be as simple as making art to the best of your abilities – or, as W.E.B. Du Bois wrote, “to use beauty to set the world right.”

Dominic Taylor does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

War in Middle East brings uncertainty and higher energy costs to already weakening US economy

Risks for the US economy grow as the war in the Middle East continues to escalate.

Venezuela’s fragile forests face rising risks as US pushes for oil and critical minerals and illegal

The Orinoco Basin is one of the most biodiverse places on the planet. It’s also rich in oil, gold…

Measuring poverty on a spectrum instead of an arbitrary line conveys a more accurate picture of ineq

An economist proposes a new method of estimating the scope of poverty in different countries.