Photographer Louis Carlos Bernal memorialized the barrios at the US-Mexican border

Even though Bernal is known as the father of Chicano photography, his work has long been overlooked. Now he’s the subject of a new exhibition at the University of Arizona.

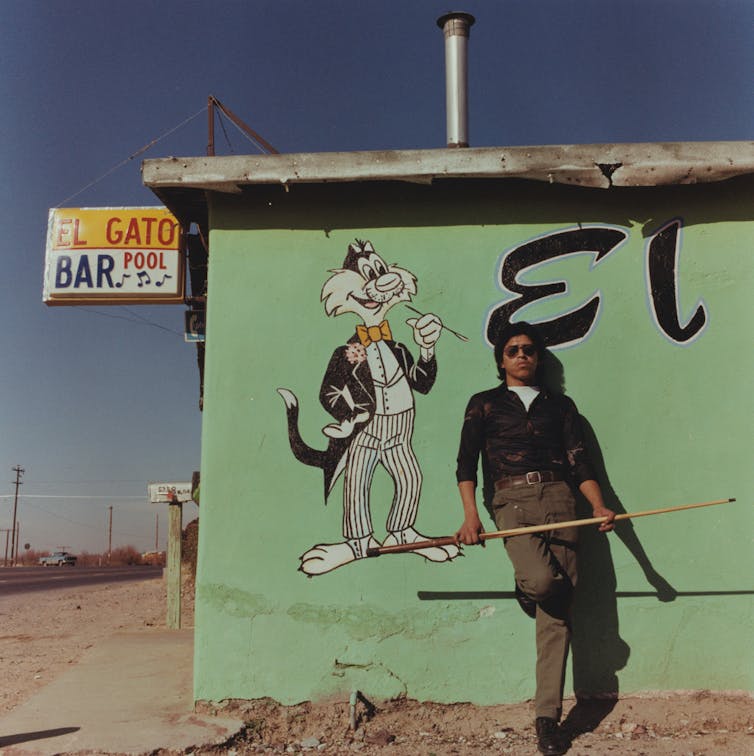

Louis Carlos Bernal, a Chicano photographer born in the Arizona border town of Douglas in 1941, invented a style of art photography that honored his Mexican American culture. In the process, he created an indelible record of life in Southwestern barrios – low-income, primarily Spanish-speaking neighborhoods – in the 1970s and 1980s.

He died tragically in 1993 when he was just 52 years old. With his photographs in only a few museum collections, his legacy received little attention over the past three decades. Now, his powerful images are reaching new audiences through a bilingual book and exhibition of 120 photographs.

As chief curator of the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona, I’ve been working with Bernal’s photographs over the past decade. In 2014, his family donated his photographs, negatives, contact sheets, working materials and memorabilia, which allowed us to establish the Louis Carlos Bernal Archive at the center.

The exhibition, which runs from Sept. 14, 2024, to March 15, 2025, will feature the portraits of everyday Mexican Americans from his most famous series of photographs, “Barrios.” And thanks to the work of photography scholar Elizabeth Ferrer, we’ve learned even more about Bernal’s artistic technique, process and goals.

Capturing ‘Chicanismo’

As a child, Bernal was given a camera and became captivated by making photographs. He enrolled at Arizona State University thinking he would become a Spanish teacher, but his fascination with photography won out.

Bernal pursued various projects as he deepened his exploration of photography. He created collages featuring iconic images of former president John F. Kennedy, who, as the first Catholic president, was particularly revered in the Mexican American community. Responding to the Watergate hearings, and interested in the impact of media on public perception, he worked on a series in which he instructed family members to hold a life-size mask of Richard M. Nixon up to their faces. Emulating the work of one of his mentors, visual artist Frederick Sommer, he made abstract images using sculptural cut paper.

Ultimately these experiments gave way to a rich and sustained project of photographing Mexican Americans and their homes.

In doing so, he turned his neighbors, relatives and other Chicanos living in the Southwest into his artistic subjects. Together, the images convey Bernal’s goal of expressing his Mexican American pride, known as “Chicanismo.”

In this way, he was a part of the Chicano art movement, which sought to address the political and cultural concerns of the Mexican American community. Chicano artists highlighted issues such as labor exploitation, immigration, gender roles and racial discrimination. Their goal was to upend stereotypes about Mexican Americans, critique the status quo and cultivate a shared cultural identity.

‘Art of and for the people’

Bernal’s photographs might remind some viewers of snapshots found in a family album, and they do share many qualities with family photographs: They feature people in everyday settings; the subjects are often centered, posing naturally and appearing relaxed; and he preferred color photography, which, by the 1970s, had become a popular way to document birthday parties, holidays and other family milestones.

Bernal, however, gave a lot of thought to the elements in each photograph. He had a process for making pictures just as he envisioned them.

Throughout the many photographs he took inside homes and businesses, and of gatherings of relatives and friends, he deliberately highlighted personal possessions: framed family photographs, altars, posters, religious icons, textiles, and floral and seasonal decorations. Beyond the people in the images, he wanted to convey themes of family, spirituality, home and community.

In a 1982 video interview, Bernal described his process, and how he would “(work) things out in advance in my head before going out.”

This allowed him to work quickly when he was in someone’s home, minimizing the imposition his presence might cause. He also liked to photograph variations of the same setting – for instance, a room with and without family members, or a scene in both color and black and white. Later, he reviewed all the options, selecting the best from a group of images with subtle differences.

In this way, he was able to create photographs from the world around him based on his deep familiarity with Chicano life and culture. These images introduced a way of life to people beyond the barrios. But they held up a mirror for other Mexican Americans, who could easily recognize the scenes.

“The Chicano artist cannot isolate himself from the community,” Bernal said in 1984, “but finds himself in the midst of his people creating art of and for the people.”

Elevating the everyday

Bernal’s process can be seen in a pair of typical portraits.

In “6th Street Barrio, Douglas, Arizona, 1979,” Bernal photographs a young boy in the living room of his family’s home.

The boy represents one point of a triangular composition. A dark brown, upholstered couch acts as the other, while family photographs high on the yellow wall form the apex. Bernal situated himself across from the corner of the room, where a small end table covered with the family’s possessions sat.

The triangular arrangement of the photograph’s key elements – and the symmetry of the vertical line formed by the room’s corner at center – gives the image balance, stability and permanence, reflecting the way family and home serve as an anchor for the Chicano community.

In “Leon Speer’s Barber Shop, Felix Valdivezo & Daughter Patricia, Lordsburg, New Mexico, 1978,” Bernal places the wall of the barbershop parallel to his lens. This choice creates an organized, composed and easily understood environment in which to make a photograph of the barber, the customer and the customer’s daughter.

Through this perspective – and with some help from a row of mirrors and lights – Bernal captures a little world in its entirety, from the tiled floor reflecting sunlight to the collection of items on a shelf below the pressed-tin ceiling. In doing so, Bernal elevates an ordinary place and everyday people as something special to behold. Instead of the spontaneous and candid qualities you might expect from the casual documentation of, say, a child’s first haircut, Bernal has used a deliberate and formal approach, rendering a familiar subject art-worthy.

Bernal’s legacy

Bernal was building this incredible document of contemporary Mexican American culture when his life was cut short.

He had built the photography program at Pima Community College, in Tucson, Arizona, and his photography practice was thriving. But in 1989, as he was biking to work, he was struck by a car. He spent the next four years in a coma, passing away on his birthday in 1993, at age 52.

Although he had achieved acclaim in the U.S., his career was more acknowledged in Mexico, where he had developed a strong community and thriving professional network. Following his death, his work was not widely circulated in the U.S.

With the establishment of his archive, the publication of “Louis Carlos Bernal: Monografía,” and the opening of a large exhibition celebrating his work, I hope his Chicano pride and artistic vision will be introduced to a new generation of viewers, cementing his legacy in the history of American art.

Rebecca Senf works for the Center for Creative Photography, the non-profit hosting the Louis Carlos Bernal exhibition. The Center for Creative Photography received funding for this project from the Henry Luce Foundation.

Read These Next

What Olympic athletes see that viewers don’t: Machine-made snow makes ski racing faster and riskier

US Olympic skiers and scientists explain the sharp differences between natural snow and machine-made…

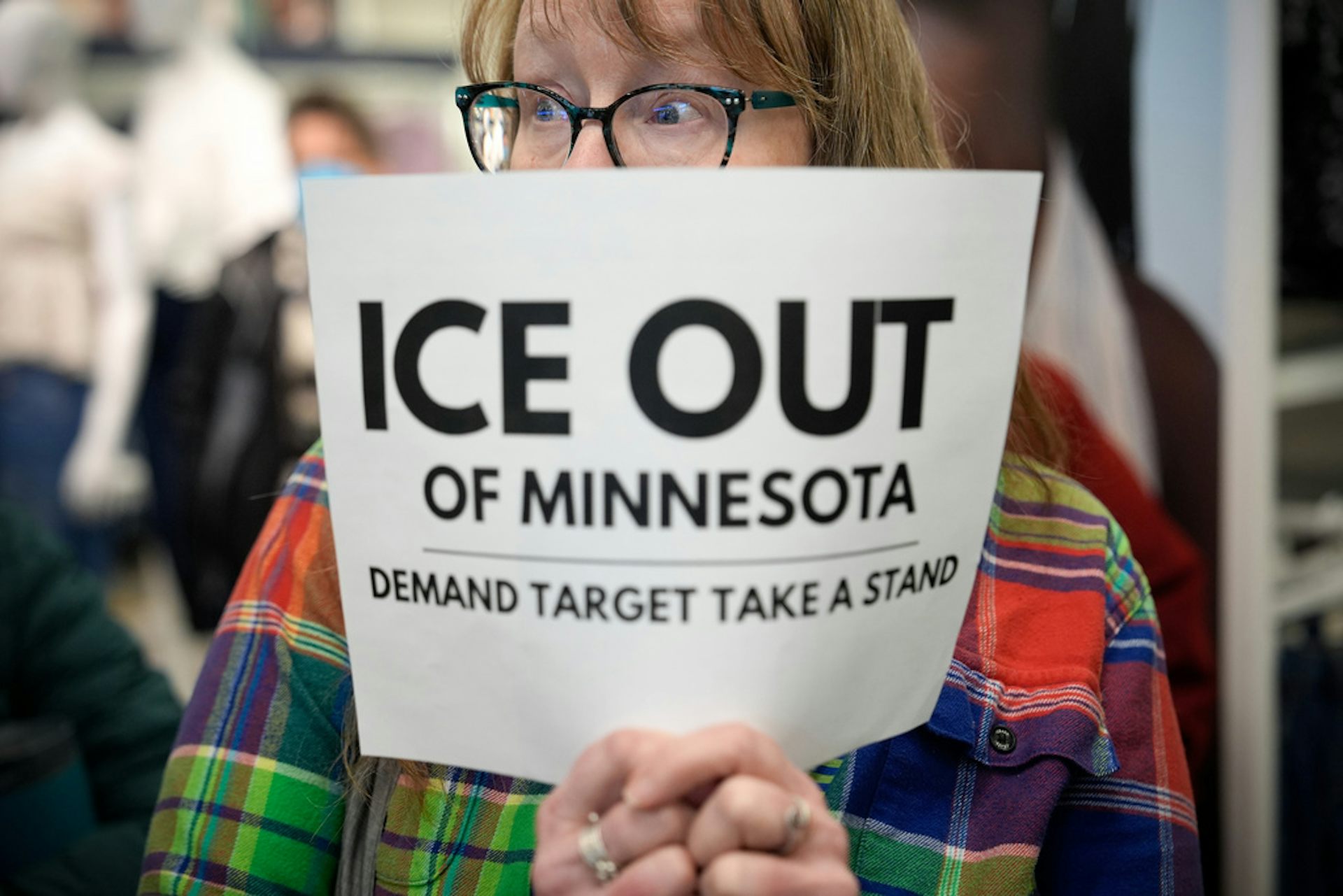

Why corporate America is mostly staying quiet as federal immigration agents show up at its doors

Federal immigration raids in Minnesota prompted a social backlash. But the business community is largely…

Has Little Caesars Arena boosted economic activity in Detroit? We looked at hotel and short-term ren

In 2026, Little Caesars Arena will host the Pistons, Red Wings and concerts with A$AP Rocky and Cardi…