For over a century, baseball’s scouts have been the backbone of America’s pastime – do they have a f

Even with teams’ embrace of analytics, the number of scouts employed by MLB teams had stayed remarkably consistent. That all changed with the COVID-19 pandemic.

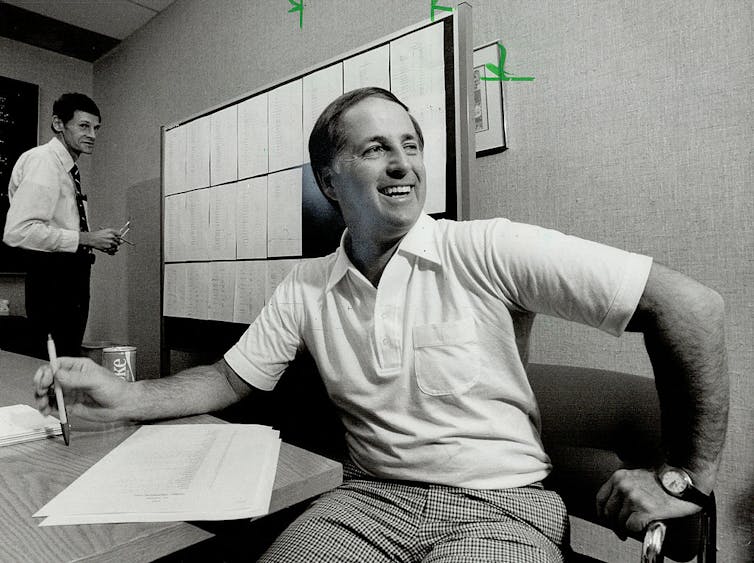

Former MLB executive Pat Gillick won three World Series titles and served as general manager of four baseball teams from the 1970s to 2000s.

But when we interviewed him for our documentary “Fielding Dreams: A Celebration of Baseball Scouts,” he deflected praise.

“I wouldn’t be in the Hall of Fame if it wasn’t for the people in scouting,” he said. “Those are the people that deserve all the credit, not me.”

Even though they scour the world for talent, often working on year-to-year contracts and spending weeks away from their families, there are no scouts in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Their recent run of tough luck has also gone largely unnoticed. The profession has been under siege on a number of fronts, whether it’s facing competition and dismissal from analytics advocates, or experiencing mass layoffs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A draft demands an army of evaluators

In the first half of the 20th century, scouting was a free-for-all.

Team owners willing to spend the money could send scouts to go out and sign whomever they wanted, with contracts often written out by hand and players signing on the spot. When Iowa teen phenom Bob Feller was signed by Cleveland Indians scout Cy Slapnicka in 1935, Slapnicka simply took out a pen, wrote out a contract and had Feller and his father sign it, because Feller was underage.

The terms of the contract? One dollar and an autographed ball.

Major League Baseball held its first draft in 1965, in part to help level the playing field between wealthier teams, like the New York Yankees and St. Louis Cardinals, and everybody else.

The advent of the draft made scouts all the more important: Each team now had a massive pool of players to interview, evaluate and rank.

The draft only includes U.S. amateur players. International players are not subject to the draft, so some teams have built training facilities in countries like the Dominican Republic and Mexico, where their international scouts find and sign promising young players.

Strength in crunching the numbers?

But since the turn of the century, some journalists and executives have questioned the value of scouts.

In 2003, author Michael Lewis published “Moneyball,” in which he documented the success of the 2002 Oakland Athletics and the team’s embrace of sabermetrics, the statistical analysis of baseball data.

The Athletics were consistently winning with one of the lowest payrolls in baseball, and other team owners took notice.

Could data analytics exploit inefficiencies and produce better results than scouts? Could teams save money by trimming the ranks of old-school professionals and all of the human bias that they brought to evaluating talent?

The embrace of sabermetrics changed who got drafted. With raw data becoming increasingly important, college players – with a longer track record of statistics – became more attractive than high school athletes.

The shift to data-informed decision-making has had some unintended consequences.

In order for high school players to get recognized in today’s environment, they turn to travel teams, an expensive option that allows a player to participate in more games and accumulate more experience, more footage of their play and more exposure.

Players from lower-income families often can’t afford to participate – and that includes young Black athletes, who are disproportionately more likely to grow up in poverty. A recent study found that Black athletes represented just 6.2% of MLB players on 2023 opening day rosters, down from 18% in 1991.

As retired Black utility player Lou Collier told us: “A kid like me, today, never would have had an opportunity. … If I wasn’t able to afford any of these events, you never would have heard of Lou Collier. But back when I was coming up, the scouts found the Lou Colliers.”

‘Moneyball’ or makeup?

Scouts will also tell you that analytics is nothing new.

“We evaluated the player,” says former Atlanta Braves scouting director Roy Clark. “And when our scouts said, ‘We think this guy can play in the big leagues,’ the next thing we did is we gathered all the information we could – analytics. But then we emphasized makeup.”

It is a grasp of this concept – “makeup,” or a player’s character, drive and grit – that scouts say differentiates their work from data-driven evaluations.

“It comes down to the people who have a really good head on their shoulders,” says Matt O’Brien, a scout for the Toronto Blue Jays.

And the scouts will tell you that there is both on-field and off-field makeup.

“You’ve got to talk to his school counselor, you’ve got to talk to his coach, you’ve got to talk to his teammates, you’ve got to try and talk to other students,” explains Gillick. “Is he a good baseball player, and is he a good human being?”

This personalized approach, one that focuses on a player’s heart and mind, has kept scouting relevant. Even with the rise of analytics, the number of MLB scouts had stayed remarkably consistent into the 21st century. It seemed as if the fear generated by “Moneyball” was unfounded.

That all changed in 2020.

The costs of COVID-19

COVID-19 didn’t just shorten the 2020 baseball season, winnowing it down from 162 games to 60. It also shrank baseball’s scouting ranks.

USA Today reported that about 20% of scouts were laid off in 2020. Many of them weren’t hired back.

“It was just the most uneasy feeling,” recalled MLB Scouting Bureau’s Christie Wood, one of the few female scouts in the game.

According to the magazine Baseball America, by 2021 seven teams had reduced their scouting staff by double digits.

The Tampa Bay Rays and Milwaukee Brewers cut 10 scouts apiece. The Los Angeles Dodgers and San Francisco Giants had 13 fewer on their payrolls. The Chicago Cubs were down 20, while the Los Angeles Angels and Seattle Mariners each reduced their scouting ranks by 23.

At the beginning of the 2019 season, teams employed 1,909 scouts across their amateur, professional and international departments. By 2021, that number was down to 1,756. And most of the scouts that were laid off were older, more experienced scouts making higher salaries.

In June 2023, 17 former scouts sued MLB for age discrimination. They claimed that the league and its teams acted intentionally to prevent the employment of older scouts after the pandemic.

A big win for the scouts

The state of scouting today is a mixed bag.

Some teams seem to be prioritizing analytics. But other organizations – the Pittsburgh Pirates, Toronto Blue Jays, Houston Astros, Minnesota Twins and Texas Rangers – have actually added scouts to their payrolls since 2019.

The Rangers organization opened their doors to our documentary crew over the past four years, allowing us into the inner sanctum. We were able to see, firsthand, the organization’s emphasis on scouting, and witness the relationships the team’s scouts built with prospects and their families.

When the Rangers won the World Series in 2023, baseball scouts around the league rejoiced: The team’s success confirmed that an emphasis on personal touch and people could still pay off.

“I’m just proud of all the scouts that are here and who have worked so hard,” Texas Rangers scout Demond Smith told us during one playoff game. “At the end of the day, it’s baseball. It’s Little League from the beginning, and then you are dreaming. And here we are.”

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Arming a Kurdish insurgency would be a risky endeavor – for both the US and Iran’s minority Kurds

Washington has long worked with Kurdish groups in the Middle East. But without sufficient support, encouraging…

Venezuela’s fragile forests face rising risks as US pushes for oil and critical minerals and illegal

The Orinoco Basin is one of the most biodiverse places on the planet. It’s also rich in oil, gold…

Today’s obsession with authenticity isn’t new – being true to yourself has troubled philosophers for

Contemporary culture seems obsessed with authenticity – but the question of how to be ‘sincere’…