How African-Americans disappeared from the Kentucky Derby

Black jockeys won more than half of the first 25 runnings of the Kentucky Derby. Then they started losing their jobs.

When the horses enter the gate for the 143rd Kentucky Derby, their jockeys will hail from Louisiana, Mexico, Nebraska and France. None will be African-American. That’s been the norm for quite a while. When Marlon St. Julien rode the Derby in 2000, he became the first black man to get a mount since 1921.

It wasn’t always this way. The Kentucky Derby, in fact, is closely intertwined with black Americans’ struggles for equality, a history I explore in my book on race and thoroughbred racing. In the 19th century – when horse racing was America’s most popular sport – former slaves populated the ranks of jockeys and trainers, and black men won more than half of the first 25 runnings of the Kentucky Derby. But in the 1890s – as Jim Crow laws destroyed gains black people had made since emancipation – they ended up losing their jobs.

From slavery to the Kentucky Derby

On May 17, 1875, a new track at Churchill Downs ran, for the first time, what it hoped would become its signature event: the Kentucky Derby.

Prominent thoroughbred owner H. Price McGrath entered two horses: Aristides and Chesapeake. Aristides’ rider that afternoon was Oliver Lewis, who, like most of his Kentucky Derby foes, was African-American. The horse’s trainer was an elderly former slave named Ansel Williamson.

Lewis was supposed to take Aristides to the lead, tire the field, and then let Chesapeake go on to win. But Aristides simply refused to let his stablemate pass him. He ended up scoring a thrilling victory, starting the Kentucky Derby on its path to international fame.

Meanwhile, men like Lewis and Williamson had shown that free blacks could be accomplished, celebrated members of society.

‘I ride to win’

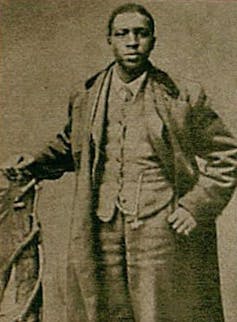

To many black Americans, Isaac Murphy symbolized this ideal. Between 1884 and 1891, Murphy won three Kentucky Derbys, a mark unequaled until 1945.

Born a slave in Kentucky, Murphy, along with black peers like Pike Barnes, Soup Perkins and Willie Simms, rode regularly in integrated competition and earned big paychecks. Black jockeys were even the subjects of celebrity gossip; when Murphy bought a new house, it made the front page of The New York Times. One white memoirist, looking back on his childhood, remembered that “every little boy who took any interest in racing…had an admiration for Isaac Murphy.” After the Civil War, the Constitution guaranteed black male suffrage and equal protection under the law, but Isaac Murphy embodied citizenship in a different way. He was both a black man and a popular hero.

When Murphy rode one of his most famous races, piloting Salvator to victory over Tenny at Sheepshead Bay in 1890, the crusading black journalist T. Thomas Fortune interviewed him after the race. Murphy was friendly, but blunt: “I ride to win.”

Fortune, who was waging a legal battle to desegregate New York hotels, loved that response. It was that kind of determination that would change the world, he told his readers: men like Isaac Murphy, leading by example in the fight to end racism after slavery.

Destined to disappear?

Only a few weeks after the interview with Fortune, Murphy’s career suffered a tremendous blow when he was accused of drinking on the job. He would go on to win another Kentucky Derby the next spring, riding Kingman, a thoroughbred owned by former slave Dudley Allen, the first and only black man to own a Kentucky Derby winner. But Murphy died of heart failure in 1896 at the age of 35 – two months before the Supreme Court made segregation the law of the land in Plessy v. Ferguson.

Black men continued to ride successfully through the 1890s, but their role in the sport was tenuous at best. A Chicago sportswriter grumbled that when he went to the track and saw black fans cheering black riders, he was uncomfortably reminded that black men could vote. The 15th Amendment and Isaac Murphy had opened the door for black Americans, but many whites were eager to slam it shut.

After years of success, black men began getting fewer jobs on the racetrack, losing promotions and opportunities to ride top horses. White jockeys started to openly demand segregated competition. One told the New York Sun in 1908 that one of his black opponents was probably the best jockey he had ever seen, but that he and his colleagues “did not like to have the negro riding in the same races with them.” In a 1905 Washington Post article titled “Negro Rider on Wane,” the writer insisted that black men were inferior and thus destined to disappear from the track, as Native Americans had inevitably disappeared from their homelands.

Black jockey Jimmy Winkfield shot to stardom with consecutive Kentucky Derby victories in 1901 and 1902, but he quickly found it difficult to get more mounts, a pattern that became all too common. He left the United States for a career in Europe, but his contemporaries often weren’t so fortunate.

Their obituaries give us glimpses of the depression and desperation that came with taking pride in a vocation, only to have it wrenched away. Soup Perkins, who won the Kentucky Derby at 15, drank himself to death at 31. The jockey Tom Britton couldn’t find a job and committed suicide by swallowing acid. Albert Isom bought a pistol at a pawnshop and shot himself in the head in front of the clerk.

The history of the Kentucky Derby, then, is also the history of men who were at the forefront of black life in the decades after emancipation – only to pay a terrible price for it.

Katherine Mooney does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

Read These Next

Failure of US-Iran talks was all-too predictable – but Trump could still have stuck with diplomacy o

Silence from the US side after a third round of indirect talks and frustration expressed by President…

Massive US attacks on Iran unlikely to produce regime change in Tehran

President Trump has appealed to Iranians to topple their government, but a popular uprising is unlikely…

Iran will respond to US-Israeli strikes as existential threats to the regime – because they are

The latest attack on Iran goes far beyond previous operations by Israel and the US in both scale and…