Russian artists grapple with the same dilemma as their Soviet forebears – to stay or to go?

Can social media posts sustain Russia’s endangered dissident cultures?

With few exceptions, most Russian artists who oppose the war have been relegated to releasing songs, posting artwork or publishing articles on social media.

Boris Grebenshchikov is one artist who took to social media in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

On April 16, 2022, Grebenshchikov posted a song on the messaging app Telegram – and later on YouTube, Instagram and Facebook – with the unsettling line: “But none of us will get out of here alive.” A few days later, his feed went silent. People started to worry about his safety.

A clampdown on free speech has made life riskier for dissident artists who criticize Vladimir Putin and the war.

It’s forced many of them to flee or consider fleeing the country altogether – no easy call, because Russians traditionally haven’t looked kindly upon artists who fled during times of crisis.

The struggle against Stalin

During the Soviet era, many talented authors, poets and musicians cultivated an underground culture of opposition to resist government repression.

Different movements emerged, each with its own style and purpose.

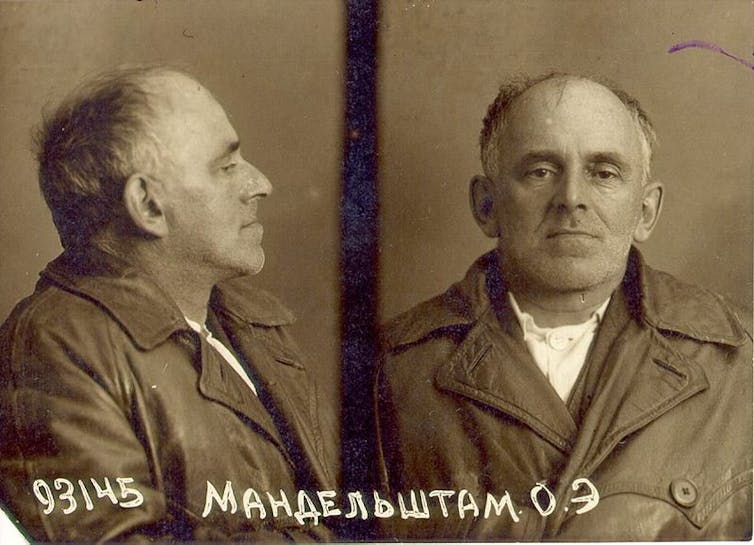

One of them, the Acmeist movement, included poets Anna Akhmatova, Nikolai Gumilev and Osip Mandelstam. The three spoke out against Joseph Stalin’s brutality at a time when he attempted to silence any artist who didn’t echo his propaganda or support his political program.

In “The Stalin Epigram,” a satirical poem written in 1933, Mandelstam wrote of the climate of terror under Stalin:

Ringed with a scum of chicken-necked bosses he toys with the tributes of half-men. One whistles, another meows, a third snivels. He pokes out his finger and he alone goes boom. He forges decrees in a line like horseshoes, One for the groin, one the forehead, temple, eye. He rolls the executions on his tongue like berries. He wishes he could hug them like big friends from home. These poets – along with many others – became targets of the regime: Gumilev was shot, Akhmatova ostracized until 1940 and Mandelstam shipped to the gulag, where he died.

Meanwhile, Stalin demanded that composers write music that was optimistic and triumphant. But for Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich, there was little to celebrate. During the Great Purge – when Stalin executed or imprisoned millions of people suspected of opposing the Communist Party – his friends kept disappearing. Family members were shot.

To evade persecution, Shostakovich wrote his Fifth Symphony to end on what appeared to be a positive note, using the same key as Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.” But importantly, the music contains instructions to be performed at half the expected speed.

The result, Shostakovich later explained, is a sound of rejoicing that feels “forced, created under threat. It’s as if someone were beating you with a stick, saying ‘Your business is rejoicing, your business is rejoicing.’”

The subtle dig didn’t register with Stalin, who interpreted the piece as a paean to his rule.

Soviet rockers long for freedom

Though there was a period of political thawing under Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrushchev, who eased repression and freed millions of people from the gulag labor camps, artists who spoke out against the regime still faced considerable risk.

Beginning in the mid-1960s, after Leonid Brezhnev assumed the Soviet premiership, rock music flourished underground, offering an expressive outlet for a generation that longed for a definitive end to censorship, oppression and persecution. These musicians were the heroes of Russian youth, and they risked their lives by performing in hidden venues with well-planned escape routes.

While state-sponsored bands such as Zemlyane and Poyushchiye Gitary appeared on television to play syrupy love ballads and sing about the country’s prosperity, dissident singers and rockers like Bulat Okudzhava and Victor Tsoi were performing in dingy basements and cramped apartments.

Songs like Victor Tsoi’s “Changes” spoke to the longing and frustration of the younger generation:

Our hearts demand changes! Our eyes demand changes! In our laughter, in our tears, And in the pulsing of our veins We are waiting for change.

The dilemma of fleeing

As Putin, like Stalin, threatens to persecute those who speak out against him, Russian artists face an age-old dilemma of suffering with their people or leaving for places where they’ll be freer to pursue their work.

Under Stalin, the poet Anna Akhmatova famously stayed put, despite the fact that some of her peers chose to leave. She was heralded for her heroism, and in 1922 she criticized those who fled with a poem titled “I’m not one of those who left their land.”

As an anthropologist studying contemporary Russian culture and society, I’ve found that Russians tend to question the allegiance of artists who left of their own accord, or didn’t come back after being exiled and given the option to return.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn, who won the Nobel Prize in literature, was sent to a labor camp in 1945, where he was imprisoned for eight years. In 1973, he was stripped of his Soviet citizenship and expelled from the country after publishing “The Gulag Archipelago,” which detailed life in Soviet forced labor camps.

Yet there were mixed feelings after Solzhenitsyn returned to Russia in 1994. Many Russians felt that, even though he had been exiled, he should have come back the instant he had been permitted to – in 1990 – and experienced the post-Soviet tumult and hardships alongside his countrymen.

Social media as a tool for resistance

While many Russians have swallowed the messages fed to them through Putin’s propaganda machine, many have not. Citizens who feel scared and disillusioned thrive on the hope they glean from artists who speak out against the war.

In a recent conversation with a friend in Russia, I asked if and how current events are discussed.

“Very carefully,” she replied. “Often by discussing the creations of our beloved artists.”

Yet acts of public defiance are becoming increasingly difficult to pull off.

Alexandra Skochilenko, a 31-year-old performance artist, faces up to 10 years in prison for disseminating “knowingly false information” after she replaced price tags in a grocery store with news reports about the war in Ukraine. Yuri Shevchuk and his band, DDT, stopped performing after Shevchuk was charged with a misdemeanor in May 2022 for insulting Putin during a show. Maria Alyokhina, the leader of the punk band Pussy Riot, recently fled Russia before she could be arrested. In order to escape, she left her cellphone behind to avoid being traced.

However, artists today have access to something their Soviet forebears didn’t: social media.

With the internet as a powerful and valuable tool for professing opposition to Putin, Russian artists are rethinking whether there’s any value in staying – and whether they might be able to more effectively resist Putin from abroad as “netizens.”

Grebenshchikov, the artist whose feed went silent in April, reappeared almost two weeks later, posting videos on Instagram, Facebook and Telegram in which he performs against a backdrop of a blue sky. It isn’t clear where he is, but with concerts scheduled internationally, it likely isn’t Russia; he’s written about his plans to perform in Cyprus, Israel and the Netherlands in the coming months.

Yes, the mass departure of artists portends the loss of in-person artistic culture in Russia. But on the other hand, online posts can, at the very least, sustain Russia’s endangered dissident cultures.

Clementine Fujimura does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Artists and writers are often hesitant to disclose they’ve collaborated with AI – and those fears ma

Whether they’re famous composers or first-year art students, creators experience reputational costs…

Algorithms that customize marketing to your phone could also influence your views on warfare

AI systems are getting good at optimizing persuasion in commerce. They are also quietly becoming tools…

Colleges face a choice: Try to shape AI’s impact on learning, or be redefined by it

Colleges and universities are taking on different approaches to how their students are using AI –…