'In the Heights' celebrates the resilience Washington Heights has used to fight the COVID-19 pandemi

Local institutions and community bonds forged during the turmoil of the 1970s and 1980s helped a vulnerable neighborhood walloped by the pandemic endure.

With camera work that swoops from rooftops to street corners, the film “In the Heights” brings to life the dynamism of northern Manhattan’s Washington Heights neighborhood.

Directed by Jon M. Chu, “In the Heights” updates Lin-Manuel Miranda and Quiara Alegría Hudes’ Tony Award-winning musical of the same name. Set in a changing neighborhood defined by Dominicans and Latino immigrants, the film eloquently expresses the feel of a hardworking place where your block is your home and a 10-minute walk is a journey to another world.

For me, the film hit home. It brought me back to the years I spent researching and writing my book “Crossing Broadway: Washington Heights and the Promise of New York City,” when I interviewed residents, walked police patrols and dug into municipal records.

In Washington Heights, long home to a mosaic of ethnic groups, some people have recoiled from human differences and huddled up in tight but exclusionary enclaves – ignorant of their neighbors at best, nasty toward them at worst.

Other residents, street-smart cosmopolitans, learned to cross racial and ethnic boundaries to save their neighborhood from crime, decayed housing and inadequate schools. In the 1990s, their efforts turned Washington Heights, once known for a murderous drug trade, into a gentrification hot spot.

My book was released in paperback during the fall of 2019. Just five months later, COVID-19 came.

Could a neighborhood already grappling with the challenges of gentrification – a prominent theme of “In the Heights” – survive a global health disaster? And could a film conceived before COVID-19 emerged speak to a city that sometimes seems to be transformed by the pandemic?

So far – and even though Washington Heights stands out in Manhattan for its suffering due to the coronavirus pandemic – the answer is a cautious yes.

But that painful victory, won with vaccines, local institutions and local ingenuity, will be valuable only if enough can be learned from northern Manhattan’s solidarity and activism to build a healthier and more just city as the pandemic recedes.

A neighborhood rife with vulnerabilities

Like other immigrant neighborhoods confronting the pandemic, Washington Heights and Inwood – the neighborhood to its immediate north – faced serious vulnerabilities.

Immigrant labor and business acumen rescued New York City from the urban crisis in the 1970s and 1980s, when white flight, job losses, a withering tax base and high crime devastated the city.

But as my co-author David M. Reimers and I pointed out in “All the Nations Under Heaven: Immigrants, Migrants and the Making of New York,” the rebuilt city is marked by inequality. Rents are astronomic, so families in Washington Heights and Inwood often double up to make costs more bearable. In the face of an easily transmitted disease, overcrowded housing was a ticking bomb.

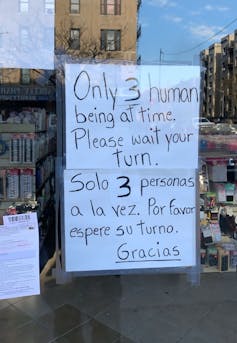

Residents in these uptown neighborhoods were also endangered by their jobs. In a city where many white-collar workers could work from home on their laptops, a disproportionate number of Washington Heights residents had to venture out to staff stores, clean buildings, deliver groceries and provide health and child care. As one uptown resident told me, her neighbors weren’t worrying about gaining 15 pounds – they were worried whether their next customer would infect them.

Equally troubling, many uptown residents had nowhere to run to. In more affluent neighborhoods, like the Upper East Side where I live, many people with country houses could decamp. In Washington Heights and Inwood, most people hunkered down in their apartments.

Bonds forged in mutual struggle

Nevertheless, Washington Heights and Inwood have strengths born in the hard experience of making a new home in New York.

The neighborhood has long been the destination of newcomers to the city, among them African Americans escaping Jim Crow, Irish immigrants putting behind them political and economic hardship, Puerto Ricans looking for prosperity, Eastern European Jews in flight from pogroms, German Jewish refugees from Nazism and Greeks expelled from Istanbul. In the 1970s, Dominicans fleeing political repression and economic hardship began to arrive in transforming numbers, along with a small but significant number of Soviet Jews escaping anti-Semitism.

For all their differences the German Jews, Soviet Jews and Dominicans had one thing in common: individual and collective memories of living with three brutal dictators – Hitler, Stalin and Rafael Trujillo. Such experiences were traumatic and could foster a tendency to stick to the safety of your own kind, but they also bred resilience.

Starting in the 1970s, and with cumulative impact by the late 1990s, significant numbers of these residents crossed racial and ethnic boundaries to revive and strengthen their neighborhood.

Thirty years later, when federal authority was absent and the pandemic surged, public-spirited residents – fortified by community institutions – stepped up again. In both cases, it was a clear example of what the sociologist Robert J. Sampson has called “collective efficacy.”

The community steps up

Back when the neighborhood was ravaged by the crack epidemic, Dave Crenshaw, the son of African American political activists, took action. Crenshaw set up athletic activities with the Uptown Dreamers – a youth group that combined sports, community service and educational uplift. The program gave young people, especially women, an alternative to dangerous streets.

When the COVID-19 pandemic erupted, Crenshaw built on his track record. He worked with The Community League of the Heights, a community development organization founded in 1952, Word Up, a community bookshop and arts space dating to 2011, and students from Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. Together, they distributed food and masks, cleaned up grubby street corners, and got people tested and vaccinated.

Further north, the YM-YWHA of Washington Heights and Inwood, founded in 1917, built on its record of serving both Jews and the entire community. Victoria Neznansky – a social worker from the former Soviet Union – worked with her staff to help traumatized families, distribute money to people in need, and bring together two restaurants – one kosher and one Dominican – to feed homebound neighborhood residents.

At Uplift NYC, an uptown nonprofit with strong local roots, Domingo Estevez and Lucas Almonte had anticipated, during the summer of 2020, running summer programs that included a tech camp, basketball and a youth hackathon. When the pandemic struck, they nimbly shifted to providing culturally familiar foods – like plantains, chickens and Cafe Bustelo coffee – to neighbors in need and people who couldn’t go outside.

Arts and media organizations eased the isolation of lockdown. When the pandemic loomed, blogger Led Black, at the local website the Uptown Collective, told readers that “solidarity is the only way forward.” In his posts he shared his griefs and vented his rage at President Donald Trump. He closed every column with “Pa’Lante Siempre Pa’Lante!” or “Forward, Always Forward!”

Inwood Art Works, which promotes local artists and the arts, shut down a film festival scheduled for March 2020 and started “Short Film Fridays,” a weekly presentation of local films on YouTube. The organization also launched the “New York City Quarantine Film Festival,” which explored topics such as life uptown in the COVID-19 pandemic, the beauty of uptown parks and the life of an essential worker.

Dreams of a better life

Of course, Washington Heights suffered during the pandemic.

Beloved local businesses vanished. Foremost among them was Coogan’s, a bar and restaurant that was the unofficial town hall of upper Manhattan, whose life and death were chronicled in the documentary “Coogan’s Way,” which is now screening at film festivals.

Families were forced to live with unemployment, isolation and fear of infection. As the social fabric frayed, loud noise levels and reckless driving of motorcycles and all-terrain vehicles raised alarm. Worst of all, the neighborhood’s residents died at rates greater than in Manhattan overall.

In Washington Heights and the rest of New York City, the coronavirus pandemic exposed long-brewing inequalities. It also illuminated character, community, strong local institutions and dreams of a better life. All these receive loving and lyrical attention in “In the Heights.”

We live, I believe, in an era when it is important to see the strengths that immigrants and their institutions bring to our cities. This film could not have come at a better time.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]

Robert W. Snyder does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Are women board members risk averse or agents of innovation? It’s complicated, new research shows

The effect of women board members on patent activity hinges on whether the company is meeting performance…

FDA rejects Moderna’s mRNA flu vaccine application - for reasons with no basis in the law

The move signals an escalation in the agency’s efforts to interfere with established procedures for…

How the 9/11 terrorist attacks shaped ICE’s immigration strategy

The growth of today’s aggressive immigration tactics traces back 25 years, when enforcement took on…