Before Martin Luther, there was Erasmus – a Dutch theologian who paved the way for the Protestant Re

Martin Luther is credited with initiating the split in Christianity that came to be called the Protestant Reformation. But don't count out Erasmus, an early proponent of similarly radical ideas.

Martin Luther, a German theologian, is often credited with starting the Protestant Reformation. When he nailed his 95 Theses onto the door of the church in Wittenberg, Germany on Oct. 31, 1517, dramatically demanding an end to church corruption, he split Christianity into Catholicism and Protestantism.

Luther’s disruptive act did not, however, emerge out of nowhere. The Reformation could not have happened without Desiderius Erasmus, a Dutch humanist and theologian.

As a scholar of medieval Christianity, I have noticed that Erasmus does not get much attention in conversations on the Reformation. And yet, in his own time, when Christianity was facing many controversies, he was accused of paving the way for Martin Luther and even of being a heretic. His contemporaries charged him with “laying the egg that Luther hatched.”

Who was Erasmus?

Born in A.D. 1467, about 20 years before Luther, Erasmus grew up in the Netherlands. The world of his youth, like that of Martin Luther’s, was almost entirely defined by medieval Christianity. Educated by monks, Erasmus joined the religious life. He studied Christian theology at the University of Paris and followed this interest even after he left the university.

At the same time, Erasmus was greatly inspired by the classics. For Erasmus, ancient Greek and Roman authors – while technically pagan – were “the very fountain-head” of “almost all knowledge.”

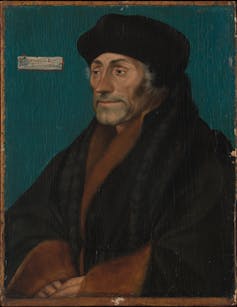

Because of his love of the ancients, he is often called a Renaissance humanist, or, more appropriately, a Christian humanist. At a time when training in Greek and Latin was highly valued, Erasmus’ remarkable abilities made him much sought after.

With the support of wealthy patrons, he traveled around Europe, teaching at universities, writing books and meeting many prominent people. In England, he formed a close, intellectual friendship with the English author and fellow humanist Thomas More, whose book “Utopia” was about an imaginary society.

Together with More, Erasmus helped launch the career of one of the greatest artists of the 16th century, Hans Holbein, who painted both of their portraits. Erasmus’ portrait, along with many other masterpieces by Holbein, is now held at New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Erasmus paves way for Luther

Luther famously used the printing press to publish polemical tracts that attacked the church and called for changes. The rapid and broad distribution of his ideas accelerated the Reformation.

It was Erasmus, however, who provided a model for Luther in how to take advantage of this new technology, how to use print as “an agent of change.”

Erasmus began publishing his books widely beginning in 1500, about 50 years after the first printed books appeared in Germany. He helped create an audience for Luther’s writings by popularizing Christian topics, such as how to be a good Christian and how to interpret the Bible. Many of his books were best-sellers during his lifetime.

Erasmus also prepared the way for one of Luther’s most radical ideas: that the Bible belongs to everyone, including common people. Luther translated the Bible into German in 1534 so that everyone could read it for themselves.

This idea can be found in Erasmus’ guide to reading the Latin Bible, “Paraclesis,” which he published in 1516 in Latin. Here he vividly describes his own dream of the future, that common people would use the Bible in their everyday lives.

“I would to God the plowman would sing a text of scripture at his plow and that the weaver at his loom would drive away the tediousness of time with it,” he wrote.

Not a supporter of radical change

Although Erasmus was sympathetic to Luther’s critique of church corruption, he wasn’t ready for the kind of radical changes that Luther demanded.

Erasmus wanted a broad audience for his books, but he wrote in Latin, the official language of the church. Latin was a language that only a small number of educated people, typically priests and the nobility, could read.

Erasmus had criticized the church for many of the same problems that Luther later attacked. In one of his most famous books, The “Praise of Folly,” he mocked priests who didn’t read the Bible. He also attacked the church’s use of indulgences – when the church took money from people, granting them relief from punishment for their sins in purgatory – as a sign of the church’s greed.

When Luther started getting into trouble with church authorities, Erasmus defended him and wrote him letters of support. He thought Luther’s voice should be heard.

But he did not defend all of Luther’s teachings. Some, he felt, were too divisive. For example, Luther preached that people are saved only by faith in God and not by good deeds. Erasmus did not agree, and he did not want the church to split over these debates.

Throughout his life, Erasmus forged his own approach to Christianity: knowing Christ by reading the Bible. He called his approach the “Philosophia Christi,” or the philosophy of Christ. He thought that learning about Jesus’ life and teachings would strengthen people’s Christian faith and teach them how to be good.

Erasmus’ ability to defend different points of view, the church’s and Luther’s, seems to have been particular to him. He wanted concord and peace within the church. Scholar Christine Christ von-Wedel describes him, therefore, as a “representative and messenger of a free and open-minded Christianity founded on scripture.”

After his death in 1536, his reconciliation of different views became impossible. The Reformation began a splintering that persists today.

[ You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can get our highlights each weekend. ]

Katherine Little does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

The apocrypha, Christianity’s ‘hidden’ texts, may not be in the Bible – but they have shaped traditi

‘Apocrypha’ means ‘hidden’ in Greek, but it is often used to describe texts that are outside…

Honoring Colorado’s Black History requires taking the time to tell stories that make us think twice

This year marks the 150th birthday of Colorado and is a chance to examine the state’s history.

50 years ago, the Supreme Court broke campaign finance regulation

A gobsmacking amount of money is spent on federal elections in the US. The credit or blame for that…