Trump’s Greenland threats reveals no-win dilemma at the heart of European security strategy

European publics and more government leaders are questioning the value of the alliance with the United States under Trump. But a different path remains elusive.

In the days since a fractious World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzeland, ended, some of Europe’s main players have pushed a narrative of continental togetherness. “Trump makes us feel not only German, but also European,” said one influential figure – German soccer star Leon Goretzka.

If even on hypercompetitive fields of European soccer the talk is of unity, then Goretzka – and the plethora of political leaders who have echoed such sentiments – has a point.

But nonetheless, the Davos meeting was yet another dizzying moment for Europe in the age of Trump. It was, to use soccer parlance, a real “game of two halves.”

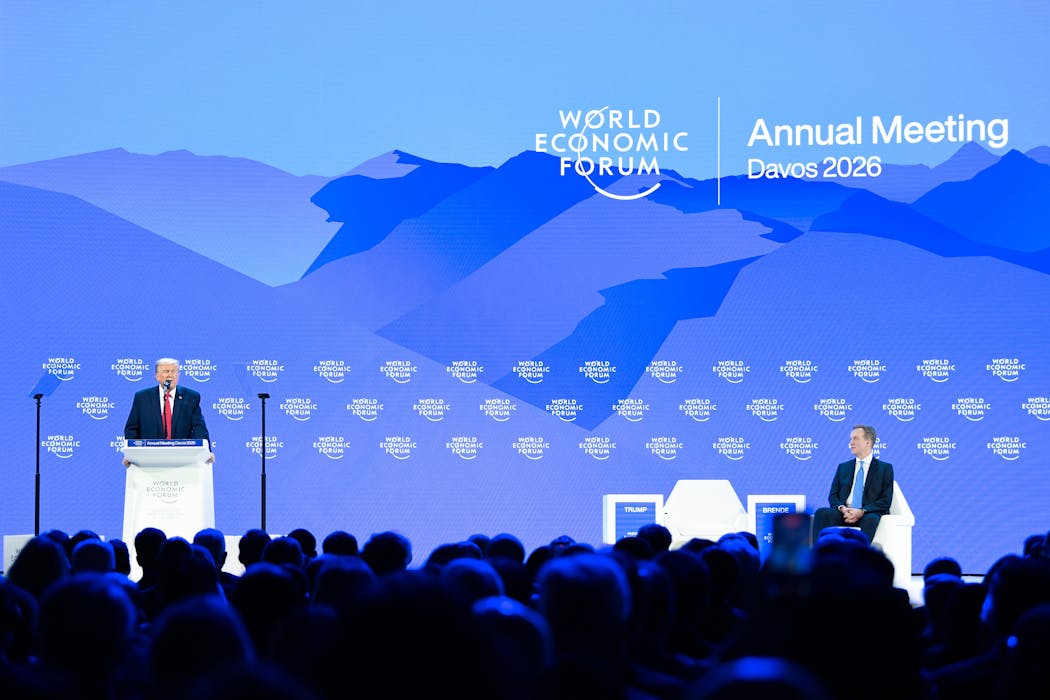

In the first, the U.S. president used his speech on Jan. 21, 2026 to belittle allies and launch a full-frontal verbal assault on the transatlantic alliance. Trump also stuck to his warning that Greenland – a territory of Denmark – would eventually join the U.S., even if he took the military option off the table that his rhetoric had previously suggested. Within hours, however, Trump had suddenly backed down from threats that included new tariffs on a selection of European partners.

In the second half, Trump vowed to scrap any new U.S. trade barriers and announced the framework of an Arctic security deal, negotiated with NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte.

On the surface, the Greenland crisis may seem defused, much to the relief of Europe. But the episode undoubtedly shook the American-European alliance to its foundations.

As a scholar of transatlantic relations, I believe Trump’s direct threats over Greenland have perhaps more than any other issue revealed Europe’s significant security dilemma. Indeed, navigating foreign relations with the U.S. will remain challenging because of Trump’s unpredictability and apparent ambivalence about maintaining decades of transatlantic security cooperation, the lack of a consistent European approach, and Washington’s willingness to exploit any vulnerabilities among its allies.

If Davos can be said to have ended in a 1-1 draw, then Europe should be aware that many soccer ties result in a rematch.

Managing Trump’s unpredictability

Despite the high tension on display at Davos, the picture was not entirely negative for Europe. In the face of pressure from Trump, Europe did maintain a united stand in defense of sovereignty and territorial integrity. It also showed mettle by threatening various economic countermeasures, such as suspending a pending U.S.-European Union trade deal and promising counter-tariffs. And it showed that Europe had learned lessons from past tussles with Trump. Indeed, EU leaders had bickered publicly during the summer 2025 negotiations over a U.S.-EU trade agreement, leading to a less-than-favorable deal.

Yet Europe should not take too much comfort from this Greenland dispute, either. Europe cannot be entirely sure that its resolve was decisive in convincing Trump to back down. His motivations remain somewhat unclear, and other factors, such as sliding bond markets, could have been a bigger mitigating influence on the U.S. president. Moreover, the framework of the accord that Trump discussed with NATO’s Rutte is short on details, which keeps the possibility open that Trump might soon restart the fight.

Lastly, even if Trump were to renounce to his Greenland ambitions, likely for lack of good options in acquiring it, Europe could hardly rest on its laurels. Trump’s unpredictability remains a major challenge, considering the next crisis might just be a social media post away.

The lack of a unified approach

Europe’s resolve to defend sovereignty and territorial integrity cannot single-handedly erase the lingering divergences that exist in terms of handling Trump. Besides their differences in personalities and ideologies, European leaders are divided into broad camps that range from those willing to confront Trump, such as Emmanuel Macron of France, to those, like Andrej Babiš, the prime minister of the Czech Republic, who are more sympathetic. In the middle are a large group of countries, including Germany and Italy.

European leaders also have to contend with the fact that historical ties with the U.S. are not uniform among their countries.

Moreover, the unfolding of the dispute at Davos did not unambiguously settle what would be the best course of action moving forward. Since the reasons behind Trump’s change of heart remain murky at best, the different European camps are likely to believe that their preferred paths were validated.

Those like Rutte who still believe Trump can be managed would have been reassured by his eventual retreat; the more confrontational advocates like France would have equally seen confirmation of Europe’s need to prepare for the worst, in part as a way of using leverage to get Trump to back down.

Davos was, in some respects, Europe’s Rorschach test. And this matters greatly because Europe is not without means or tools to push back against Trump in any future crises. It could invoke retaliatory tariffs when need be, dump U.S. assets – particularly its large holdings of U.S. bonds – or even invoke the Anti-Coercion Instrument, the so-called trade bazooka. The latter would be a significant move that would restrict U.S. access to the EU market. It could also hit Silicon Valley particularly hard, since the Anti-Coercion Instrument could pull the plug on social media companies or prevent them from investing in Europe. None of those measures, however, would be effective – or indeed, in some instances even possible – absent greater unity and political will.

Dangerous dependence?

If anything, the spat over Greenland is a powerful reminder that the Trump administration would not hesitate to try to coerce Europe by reminding it of its various dependencies on the U.S., particularly in the form of what Washington has often framed as military freeriding. Yet, in determining how to respond to that drastic challenge, Europe finds itself caught between a rock and a hard place.

On the one hand, the repeated hostile words and actions by the Trump administration could push Europe to adopt a more confrontational approach. After all, U.S. brinkmanship on Greenland is likely to weaken, if not remove, the case for further accommodation of Trump.

This is also connected to a broader rejection of Trump across the European public. An overwhelming majority view him as a negative force for peace and security, whereas only 16% of the public now regard the U.S. as an ally. This disaffection even gained ground over Greenland among European far-right populist parties, who are normally more MAGA-friendly.

But on the other hand, European leaders have to temper this domestic push for a more assertive stance with the realities of their multiple dependencies on the United States. These vulnerabilities, in turn, could very well be weaponized by Trump. Thus, Europe’s decision to move away from Russian gas after 2022 included a shift to buying more U.S. liquefied natural gas. That could easily become a pressure point.

Moreover, tech also looms large as an area where the U.S. could punish Europe if it wanted. A nightmare scenario could thus entail the U.S. cutting off Europe’s “access to data centers or email software that businesses and governments need to function,” as The Wall Street Journal recently reported. And of course, Europe remains very mindful of its dependence on the U.S. for security, as well as the fear that Trump may suddenly abandon support for Ukraine in its conflict with Russia.

None of these dependencies can be solved or mitigated in the short term, nor does every leader draw the same conclusion as to what path to pursue. While Rutte seems resigned or if not actively sympathetic to Trump’s position, and calls European defense without the U.S. a “dream,” former Italian Prime Minister Mario Monti and former European Parliament member Sylvie Goulard disagree vehemently. In their view, the credibility of the U.S. security guarantee is less than convincing in light of Trump’s repeated attacks against Europe. In that case, why pay a price for a protection that may not even exist?

Trump’s Greenland threat was a profound shock for the transatlantic alliance. But it is far from clear if Europe can or will draw lessons to help it adopt a more united approach to preserve its security.

Garret Martin receives funding from the European Union for the Transatlantic Policy Center, an institute that he co-directs at American University.

Read These Next

Drug company ads are easy to blame for misleading patients and raising costs, but research shows the

Officials and policymakers say direct-to-consumer drug advertising encourages patients to seek treatments…

Tiny recording backpacks reveal bats’ surprising hunting strategy

By listening in on their nightly hunts, scientists discovered that small, fringe-lipped bats are unexpectedly…

Former Harvard president Summers’ soft landing after Epstein revelations is case study of economics’

Despite repeated calls for the university to revoke his tenure, the economist held onto his teaching…