Refugee families are more likely to become self-reliant if provided with support outside of camp set

With targeted support, refugees are more likely to gain employment, increase their savings and find safety if not housed in camps, study finds.

Refugees provided with targeted support outside of designated camps have a better chance of finding jobs, economic stability and safety.

That is the main finding in our recently published article in BMJ Global Health looking at what helps displaced families become self-reliant.

To establish what enables refugee households to meet their basic needs for housing, food, health care and education without depending on aid or formal assistance, we analyzed data from the self-reliance index, a tool we helped develop as academic advisers to the Refugee Self-Reliance Initiative.

The index, one of the largest known of its kind, looks at the self-reliance of refugees, internally displaced people and host community members across 16 countries. In all, it assesses 12 areas of household life – from employment and savings to health care access and safety.

Across nearly 8,000 households in our data, we found that general levels of self-reliance were extremely low, with most families unable to sustainably meet their basic needs and heavily dependent on aid.

But when we looked at households over time, we found that those living outside of camp settings showed real, measurable progress. Refugees living in cities, towns and villages were more likely to see improvements in work, savings and paying down debt. They also reported safer, more stable living conditions.

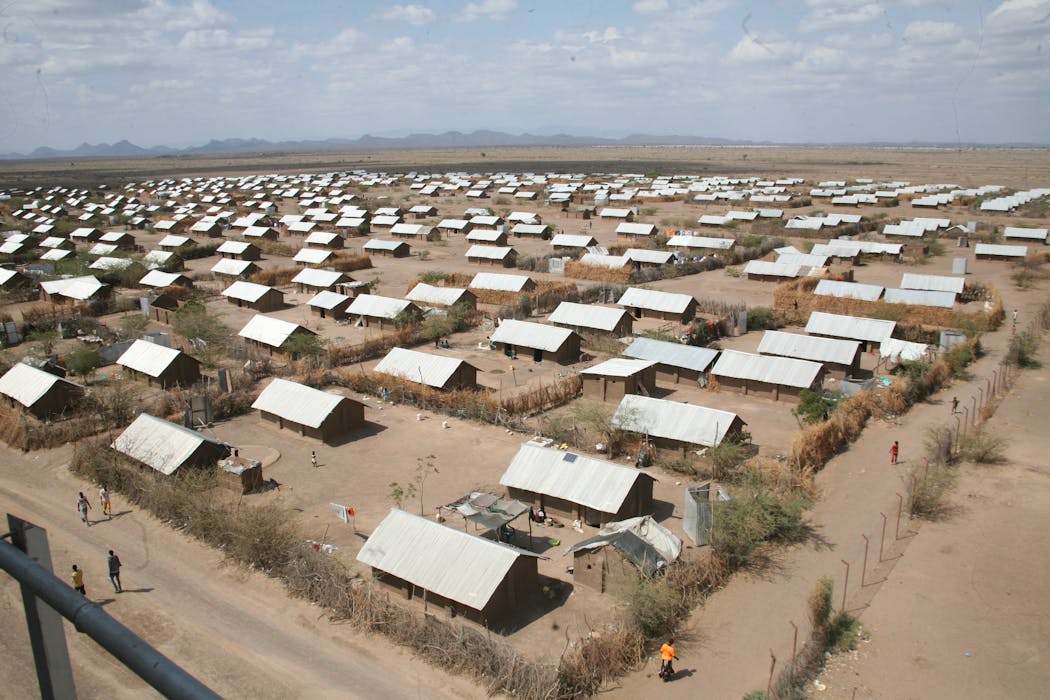

Households in camps, by contrast, didn’t show much improvement. In some areas, including education and financial resources, prospects for families living in camps actually worsened over time.

Taken together, our findings suggest that families that struggle in camp settings may thrive when given opportunities, mobility and access to markets in noncamp environments.

Why it matters

The world is experiencing the highest levels of forced displacement ever recorded. The United Nations estimated that in mid-2025 more than 117 million people were living as refugees, asylum-seekers or internally displaced peoples. The majority of asylees and refugees end up in neighboring countries, where resources are already stretched.

These modern-day realities challenge the old model of humanitarian response. Camps were designed for short-term protection and assistance. But for many of today’s refugees, displacement often lasts decades.

And although camps, by design, provide food, shelter and basic services, they also often restrict where people can go and whether they can work. They provide free or subsidized services, but these same structures can trap people in dependency when displacement stretches on for years.

Our findings show that progress is indeed possible, but only when the environment allows it. Families living outside camps proved that.

But those who live in noncamp settings face their own challenges.

Accessing services is harder, and families can face discrimination from host communities. Progress requires policies that let displaced people work, access services and move freely. It requires sustained investment in integration rather than isolation.

Making sure that funding is focused on where it can do the most good matters now more than ever. Humanitarian funding has shrunk dramatically due in part to massive cuts in U.S. assistance.

And our data clarifies an important trade-off: Blocking displaced people from working doesn’t save money. Rather, it shifts costs into the future while trapping families in dependency that requires ongoing aid.

What we don’t know

Our findings raise new questions. We know noncamp settings enable progress, but not which specific interventions matter most. Does cash assistance drive change, or is legal documentation the key? More comparative research would help governments and humanitarian agencies target investments more effectively. We also need to better understand what happens to families once they leave camp settings, and whether they have the same trajectories as those who initially settle outside of camp settings.

Meanwhile, our findings suggest a fundamental rethinking may be needed over the use of camps. If these environments structurally limit what families can achieve, continuing to measure them against self-reliance standards may be setting them up to fail. Metrics focused on safety, mental health and skill development might better capture what’s actually possible in restricted settings while preparing families for future opportunities.

The Research Brief is a short take on interesting academic work.

Lindsay Stark receives funding for her work with the Refugee Self-Reliance Initiative (RSRI). She is affiliated with the RSRI as an Academic Advisor.

Ilana Seff received funding from Refugee Self-Reliance Initiative (RSRI) for this work. She is affiliated with the RSRI as an Academic Advisor.

Read These Next

Trump’s war against Iran is uniquely unpopular among US military actions of the past century

Trump’s Iran war is historically unique in one critically important way: Early on, the war is not…

Gifts from top 50 US philanthropists jumped to $22.4B in 2025 − Mike Bloomberg, Bill Gates and the e

Three philanthropy scholars size up the latest data on gifts from the country’s biggest philanthropists.

Women of the Rosenstrasse protest challenged the Nazi regime for their detained Jewish husbands’ fre

Couples in interfaith marriages came under intense pressure in Nazi Germany. But women’s protests…