Sudan’s civil war: A visual guide to the brutal conflict

Since fighting broke out in April 2023, some 150,000 people have been killed in Sudan and an estimated 13.5 million displaced.

Sudan’s brutal civil war has dragged on for more than 2½ years, displacing millions and killing in excess of 150,000 people – making it among the most deadly conflicts in the world today.

As of December 2025, the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces appear to be making gains, seizing a key oil field in central Sudan and forcing the retreat of the Sudanese Armed Forces in key cities in the country’s west.

But fighting has ebbed and flowed throughout the war, with parts of the country changing hands a number of times. It has left a complicated picture of a nation mired in violence. Here’s a visual guide to help understand what is going on and the toll it has taken on the Sudanese population.

What military forces are involved?

The two main warring parties are the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

The SAF is the nation’s official military. Prior to the civil war, it was responsible with enforcing the border, protecting the country from foreign entities and maintaining internal security. As of April 2023, the SAF had an estimated force of up to 200,000 people.

The paramilitary RSF is a semi-autonomous organization that was created in 2013 to confront rebel groups. Its origins lie in the feared Janjaweed militia that gained international notoriety for its scorched-earth tactics, extrajudicial killings and sexual assaults during a campaign in Darfur between 2003 and 2005.

Rebranding as the RSF, the paramilitary force evolved to become President Omar al-Bashir’s personal security force before al-Bashir’s ouster in 2019.

After that, the RSF and the SAF worked together to stage a 2021 coup against Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok in 2021. But a power struggle emerged between the leaders of the RSF and SAF amid disagreements over the future direction of the country and whether the RSF would be incorporated into the army.

By the outbreak of the civil war in 2023, the RSF had amassed around 100,000 troops.

Various other armed groups have lent their support to the RSF and SAF during the conflict, including the rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North, which supports the RSF, and the army-aligned Justice and Equality Movement

Who are the main leaders?

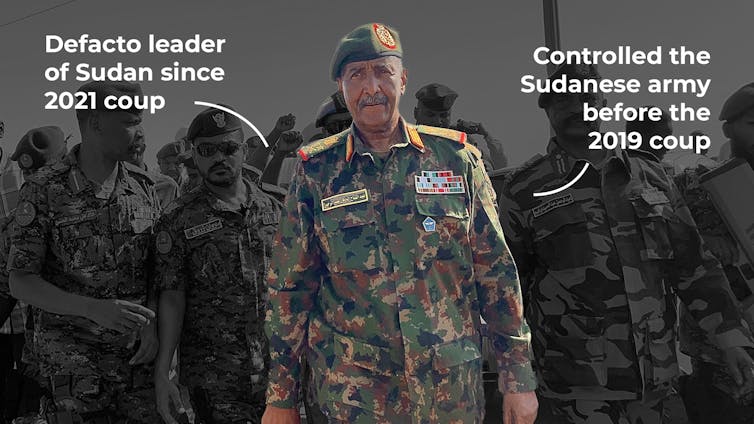

The SAF is led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the nation’s top military commander and de facto head of state. The longtime soldier rose to the rank of regional commander in 2008 and was promoted a decade later to the position of army chief of staff.

Following Bashir’s 2019 ouster, Burhan was appointed to lead the Transitional Military Council and its successor civilian-military entity known as the Sovereign Council. As leader of the Sovereign Council, Burhan occupied the nation’s highest office.

His reputation has been marred by his own military’s attacks on civilians in Darfur in the early 2000s and, more recently, his reliance on support from Islamist groups.

The RSF leader, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, also known as “Hemedti,” was Burhan’s second-in-command.

Born to a poor family that settled in Darfur, Hemedti was part of the Janjaweed militia that President Bashir deployed to crush non-Arab resistance in the country’s west. Becoming leader of the Janjaweed before going on to head the RSF, Hemedti acquired a reputation as a ruthless commander whose brutal methods disturbed some fellow officers.

Where are the weapons, funding coming from?

While the fighting has largely been contained to within Sudan’s boundaries, it is being fueled from outside the country.

Amnesty International has reported that despite a decades-old arms embargo by the United Nations Security Council, recently manufactured weapons and equipment from China, Russia, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates have been used by both sides in the conflict.

The Sudanese government has accused the UAE of providing military assistance to the RSF, which in turn has been accused of using the UAE for illegal gold trafficking.

In addition to providing military assistance, the UAE has been accused of providing economic support for the RSF. In January 2025, the Biden administration sanctioned seven UAE-based companies funding Hemedti.

Saudi Arabia, which sees Sudan as an ally to counter Iran’s regional influence, has provided financial support to the SAF. In October 2025, the SAF-backed government announced that Saudi Arabia planned to invest an additional US$50 billion into Sudan, on top of the $35 billion it has already invested.

Egypt, allied with Burhan in a dispute with Ethiopia over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, has supplied the SAF with warplanes and pilots.

Meanwhile, Iran and Russia have each extended support for the Sudanese government. It is believed that Iran, which renewed diplomatic ties with Sudan in October 2023, has provided the SAF with attack drones, while Russia has provided Sudan’s government with diplomatic and military support.

What areas are controlled by whom?

As of December 2025, the RSF and SAF control different halves of the country split along a roughly north-south axis. The SAF controls a little more than half of the country.

The SAF has a stronghold in the nation’s capital Khartoum. In the east, the army controls the city of Port Sudan on the Red Sea coast. The SAF also controls approximately three-quarters of the Sudanese border with Egypt to the north.

Strategically, the areas under SAF control provide the advantages of access to the Red Sea – a crucial transport hub through which 12% of the world’s maritime trade passes – as well as the historic demographic and administrative epicenter of Khartoum, situated at the confluence of the Blue and White Niles, and the livestock-rich Kassala state.

In all, Sudanese researcher Jihad Mashamoun estimates that as of November 2025, the SAF controlled 60% of the country.

Meanwhile, the RSF has consolidated control over Darfur – the massive western region that has been a hub for gold mining and trafficking routes – and the regional capital of el-Fasher, an economic hub connecting routes to Libya to the north, the Nile to the east and Chad to the west.

As researcher Bravin Onditi has noted, el-Fasher’s fall to the RSF in late October eliminated the SAF’s last stronghold in Darfur from which it could assert authority in western Sudan.

Outside of Darfur, the RSF controls most the country’s oil fields, many of the goldfields in central and southwest Sudan, and splits control over important grazing lands with the SAF.

What has been the toll on Sudan’s citizens?

One of the war’s distinguishing horrors has been repeated incidents of civilian killings.

Both sides have been accused of war crimes that include targeted attacks on civilians, medical centers and food systems. Mass killings in Khartoum, Darfur, Kordofan, Gezira, Sennar and White Nile states reflect the general scope of slaughter that has swept the country.

In some instances, this violence has taken on a decidedly ethnic dimension. Human Rights Watch reports that from late April to early November 2023, the RSF and its allied militias systematically sought to remove — including by murder — ethnic Masalit people from El Geneina, capital of West Darfur.

In October 2025, following the RAF’s siege of el-Fasher, the world watched in horror as satellite images of “clusters” consistent with bodies and blood-red discoloration could be seen on the ground. The U.N. Security Council held an emergency meeting condemning the RSF’s killing of nearly 500 people in el-Fasher’s Saudi Maternity Hospital.

More than 9.5 million people are classified as internally displaced, having fled violence. The International Organization for Migration reports that North and South Darfur states host the largest number of internally displaced people, followed by Central and East Darfur states.

Meanwhile, over 4 million have fled to the neighboring countries of Egypt, South Sudan and Chad.

Image sources:

FD-63 - Dağlıoğlu Silah, Saiga MK .223, Kalashnikov Group, Tigr DMR, Kalashnikov Group, M05E1, Zastava Arms, PP87 82MM mortar bomb, Amnesty International, CKJ-G7 drone jammer, Amnesty International, Streit Gladiator, Streit Group, Terrier LT-79, Streit Group, INKAS Titan-S, INKAS Armored Vehicles

Christopher Tounsel does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Will AI accelerate or undermine the way humans have always innovated?

An anthropologist’s new book lays out the formula for human innovation, from stone tools to supercomputers.…

Minneapolis united when federal immigration operations surged – reflecting a long tradition of mutua

Minnesotans from all walks of life, including suburban moms, veterans and protest novices, have bucked …

How to prevent elections from being stolen − lessons from around the world for the US

As President Trump and other Republicans cast doubt on the legitimacy of the US electoral system, other…