The Dayton Peace Accords at 30: An ugly peace that has prevented a return to war over Bosnia

More than 100,000 people were killed in the Bosnian war. But the peace that ended it in 1995 sowed the seeds for ethnonationalism.

On Nov. 21, 1995, in the conference room of the Hope Hotel on the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, the leaders of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia and Croatia initialed an agreement that brought the three-and-a-half-year war in Bosnia to an end. Three weeks later, the General Framework Agreement, known as the Dayton Peace Accords, was signed.

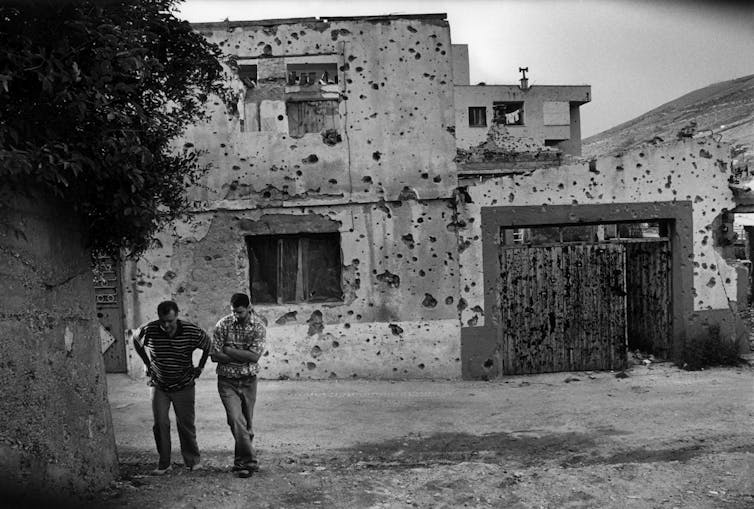

The war over Bosnia was the most brutal and devastating of the wars spawned by the dissolution of Yugoslavia. Attacked from the moment it moved toward independence in early 1992 by militias supported by the neighboring nations of Croatia and Serbia, Bosnia was born under fire and nearly perished. Half of its population of 4.4 million were forcefully displaced, and over 100,000 people died during the conflict.

Ethnic cleansing and war crimes marked the war, including the Srebrenica genocide of July 1995, in which more than 8,000 Bosniak victims were murdered by the army of Republika Srpska.

The peace agreed to at Dayton left Bosnia, or Bosnia and Herzegovina as it is known in full, intact as a country but divided into two entities, Republika Srpska – a secessionist entity proclaimed by ethnonationalist Serbs in January 1992 – and the Bosnian Federation. Meanwhile, an international military force was deployed to secure the peace.

But it was an ugly peace: The patient was saved, but left deformed and weak. As scholars who have written extensively about the Bosnian war and its aftermath, we believe the legacy of the Dayton Peace Accords, 30 years on, is decidedly mixed.

The sorting of ethno-territories

Bosnia’s life after Dayton can be divided into three roughly decade-long eras: reconstruction, stalemate and permanent crisis.

The first decade was the toughest but most hopeful. With peace enforced by an international force including U.S. and Russian troops, Bosnians returned to their war-shattered country.

But restoring the country’s social fabric proved hard. While the international community aspired to reverse ethnic cleansing, the obstacles were immense.

A once proudly multicultural country was left divided into separate ethno-territories.

Under the Dayton Accords, Bosnians were promised the right to return home. But this was complicated by the fact that many houses were destroyed, while others were occupied by those who had forcefully displaced them.

By the summer of 2004, the UNHCR, the United Nations agency coordinating returns after the peace agreement, announced that it had achieved 1 million returns. What became evident, however, is that “minority returns” – that is, people returning to places where they would be a minority community – were limited. Many returnees reacquired their old property after a struggle but promptly sold it to build a life elsewhere among people who were the same ethnicity as them.

Cross-ethnic trust was largely shattered by wartime experiences.

Incompatible horizons

The first decade was peak liberal international statebuilding. An international high representative charged with “civilian implementation” of the Dayton Accords centralized control over military and intelligence functions at the state level. A central state border service and investigations agency was created. So also was a central state court, state-level criminal codes and an indirect taxation authority to unify indirect tax collection and finance state institutions.

Bosnia’s trajectory, though, stalled in 2006 when the high representative stepped back from state building. In April 2006, a package of constitutional amendments designed to streamline Dayton by strengthening central state institutions fell two votes short in the state Parliament.

Surprisingly, the package was not blocked by parties from Republika Srpska, traditional obstructionists, but by former Prime Minister Haris Silajdžić’s Bosniak-dominated party. This failure set the stage for a decade of polarization and stalemate.

Silajdžić campaigned for abolition of the entities – Republika Srpska and the Bosnian Federation – and the creation of a single united Bosnia. Republika Srpska’s leading politician, Milorad Dodik, answered by floating the prohibited idea of an entity independence referendum.

With the high representative largely passive, Bosnia was stalemated between incompatible horizons, each side strong enough to block but too weak to prevail.

Dodik turned referendum talk in Republika Srpska into a steady repertoire of threat, while casting central state institutions in Sarajevo as rotten, artificial and destined to fail. In the process, Dodik and his family got rich, creating a classic patronal power network across Republika Srpska.

With the media thoroughly divided by wartime allegiances, the public sphere was filled with incendiary rhetoric.

The word “inat” is a shared idiom across Bosniaks, Croats and Serbs. It is stubborn uprightness, a combination of narcissism and spite. Politics increasingly rewarded those who could perform “inat” more vividly than their rivals.

Central state institutions in Bosnia did not collapse but became sclerotic. Procedures multiplied, confidence thinned and decision-making settled into a theater of anticipatory vetoes where the point was less to implement a program than to keep imagined endpoints – the creation of a unified nation on one side; an independent Republika Srpska on the other – alive and to make the other side feel the pain of their impossibility.

A country on the brink

A decade of stalemate slowly evolved into a condition of permanent crisis.

In November 2015, Bosnia’s Constitutional Court ruled that the marking of Jan. 9 as “Republika Srpska Day” – a celebration of virtual independence – was discriminatory and illegal under human rights law.

Dodik, the Republika Srpska’s de facto leader, responded by organizing an extralegal referendum whose result asserted that the Republika Srpska population wanted the date retained.

Defiance evolved into active subversion of the constitutional order and provisions of Dayton. The Republika Srpska parliament passed laws that directly challenged central state institutions built in the first postwar decade. With weak enforcement capacity, the Bosnian state was unable to command compliance.

When in 2021 a new high representative was appointed over Russian objections, Dodik rejected his authority outright. By then, Bosnia was routinely described as “on the brink” of war.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 saw Dodik side firmly with Moscow. He visited Russian President Vladimir Putin in Moscow frequently. The Republika Srpska media relayed Russian propaganda, featuring correspondents reporting live from Russia’s front lines.

Meanwhile, people and institutions in the Bosnian Federation aligned with Ukraine and the West. A giant geopolitical rift ran through the country: two entities, two different realities.

In February 2025, the drama peaked when Bosnia’s Constitutional Court barred Dodik from political life. Predictably, he rejected the top court’s authority, and a standoff ensured. Dodik hired figures close to the Trump administration such as Rudy Giuliani to lobby on his behalf. By the end of October 2025, they had succeeded in getting U.S. sanctions on Dodik removed in exchange for him agreeing to leave the Republika Srpska presidency.

The ugly peace endures

To distant observers, Bosnia may register as a success story because it has not returned to war. But the peace forged at Dayton bound Bosnia in a straitjacket that has kept it divided since.

Ethnonationalism and crony capitalism have thrived while many Bosnians have left or aspire to do so.

Yet, unloved as it may be today, the Dayton Accords preserved Bosnia. It stopped a war, enabled freedom of movement, permitted economic revival, regularized elections, revived cultural life and allowed more than 1 million people to exercise their right of return.

As peace agreements go, the Dayton Peace Accords wasn’t the worst – but it is far from the best.

Gerard Toal received funding from the US National Science Foundation in the past for research on Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Adis Maksić does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Bad Bunny says reggaeton is Puerto Rican, but it was born in Panama

Emerging from a swirl of sonic influences, reggaeton began as Panamanian protest music long before Puerto…

How to prevent elections from being stolen − lessons from around the world for the US

As President Trump and other Republicans cast doubt on the legitimacy of the US electoral system, other…

How protecting wilderness could mean purposefully tending it, not just leaving it alone

For decades, wilderness lands have been left largely unaltered by human activity. But those places are…