The lost history of Latin America’s role in averting catastrophe during the Cuban missile crisis

A common US-centric narrative holds that the Cuban missile crisis ended when Washington stood firm against the Soviets. But that story ignores a whole continent.

Sixty-three years ago, President John F. Kennedy single-handedly brought the world back from the brink of nuclear war by staring down Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev over the Cuban missile crisis. At least, so goes a standard U.S.-centric interpretation of events.

But despite the narrative of presidential strength and American resolve saving the day, the truth is more complicated – and involved a wider cast of continental characters.

As an expert in Latin American and Cold War history with a new book on the topic, I argue that when it comes to the Cuban missile crisis, it took a proverbial regional village to avert catastrophe. Indeed, the United States did not solve or experience the drama alone. Much as in geopolitics today, the Cuban missile crisis took place in a complicated environment where the entire hemisphere both reckoned with and helped shape the realities of American power and regional dominance.

Regional assistance during the crisis

On the evening of Oct. 22, 1962, Kennedy took to the airwaves and revealed to a live international audience that the Soviet Union had secretly placed nuclear-armed missiles in Cuba capable of reaching most of the mainland U.S. and Latin America.

Throughout his speech, Kennedy consistently emphasized that the missiles threatened the security not just of the U.S. but of the entire hemisphere. And because the missiles were a regional threat, they required a regional solution. Kennedy called upon the Organization of American States, a regional body created in 1948 to coordinate hemispheric affairs, including security, to invoke the 1947 Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance “in support of all necessary action” to remove the missiles.

U.S. regional neighbors responded immediately to Kennedy’s call for action.

During the crisis, Mexico and Brazil were the two Latin American countries that most enthusiastically supported a peaceful resolution. The leaders of both countries were moderate leftists and had demonstrated sympathy with the Cuban Revolution before the missile crisis. Mexico and Brazil were two of the few remaining nations in the Americas that still had official ties with Cuba and, as a result, their leaders could help facilitate shuttle diplomacy.

Mexico’s president, Adolfo López Mateos, sent a personal message to Cuban President Osvaldo Dorticós as soon as he learned about the missiles. López Mateos made a special appeal “in the name of the friendly relations that unite and have united our countries.” He stated that he believed it was his duty to “cordially call upon your government so that those bases are not used in any form whatsoever and the offensive weapons are withdrawn from Cuban territory.” By communicating directly with the Cubans, Mexico’s president treated them as full participants in the crisis on their island, not as mere victims, puppets or observers.

Mexico’s government also helped maintain surveillance in the waters around Cuba and clamped down on any pro-Cuban protests during the missile crisis. Mexico’s navy sent 10 ships to patrol the Yucatan Channel between Mexico and Cuba. The U.S. ambassador noted the lack of violent demonstrations in Mexico and attributed the peaceful public response to the “firm control maintained by national and local police and military forces.”

Like López Mateos, Brazilian President João Goulart tried to use his country’s special relationship with Cuba to convince the Cubans to make concessions during the crisis. Goulart secretly reached out to Cuban leaders through his ambassador in Havana, the Cuban ambassador in Rio de Janeiro and Cuba’s representative to the United Nations. Through these channels, he tried to convince the Cubans to open their territory to an investigative U.N. commission.

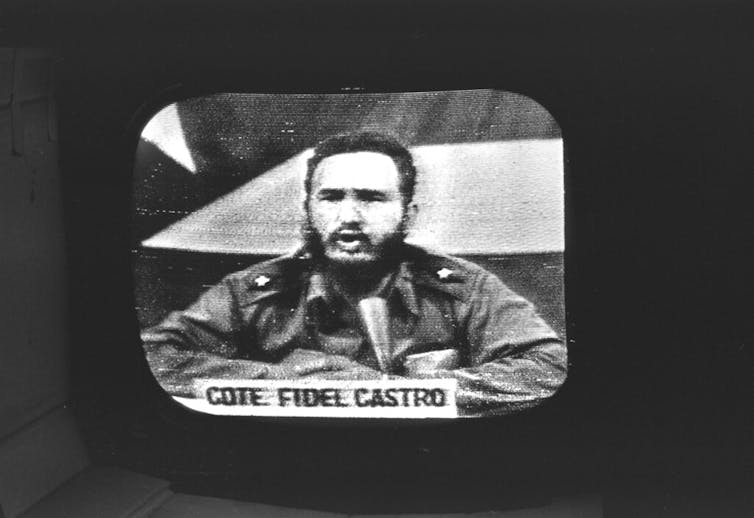

Goulart also sent a special envoy to Havana who pleaded for a peaceful resolution. This mission was actually a top secret favor to the Americans, who had asked the Brazilians to use their special relationship with Cuba to serve as mediators and suggest to Cuban leader Fidel Castro that giving up the nuclear weapons could be the first step in improving Cuba’s relations with its neighbors. “From such actions many changes in the relations between Cuba and the OAS countries, including the U.S., could flow,” the message promised.

Crafty diplomacy

Most importantly, Mexican and Brazilian leaders changed their position in international organizations in response to the Cuban missile crisis.

Prior to the crisis, these two countries had resisted all multilateral actions against Cuba and had abstained from Organization of American States votes that put sanctions on the island. But on Oct. 23, 1962, they changed their position and joined the unanimous vote to establish a quarantine around Cuba. The quarantine laid out a large zone where ships approaching the island could be intercepted and searched for offensive military equipment.

The OAS action provided the legal foundations for the quarantine. Establishing the quarantine under the auspices of articles 6 and 8 of the Rio Treaty made it a multilateral “act of common defense.” Had the U.S. acted alone, interdicting ships in international waters would have legally been considered a “blockade,” or act of war.

By voting in this manner, Latin American countries demonstrated their support not necessarily for the U.S. or U.S. imperialism, as some critics claimed, but for multilateralism. Latin American leaders were protecting their own countries, not just the U.S., when they demanded the removal of the Soviet missiles. The unanimous vote also helped the U.S. demonstrate to the rest of the world that other countries in the Americas agreed that the presence of Soviet missiles in Cuba posed an unacceptable threat.

Another Latin American country, Venezuela, not only joined the unanimous vote to establish the quarantine but also participated in it. Venezuela contributed airplanes, two destroyers and the country’s only submarine to the Inter-American Quarantine Force, a combined group of Latin American armed forces that constituted the southernmost part of the quarantine line. The Cuban missile crisis marked the first time in modern Venezuelan history that the country’s forces had participated in international military actions.

“My government will comply with each and every one of its international compromises,” declared Venezuela’s President Rómulo Betancourt, “not only out of loyalty to written agreements in treaties that impose inevitable obligations, but also out of a sense of national survival.”

Inevitable obligations and national survival

The Venezuelan president’s declaration about his country’s response to the crisis reminds Washington what it may be forsaking and risking with today’s current policy toward Latin America.

During the Cuban missile crisis, Kennedy and Latin American leaders took their international obligations seriously and used international law to their advantage instead of defying it. In comparison, recent months have seen the Trump administration flout international norms by carrying out unilateral strikes on ships in Caribbean and Pacific waters.

Kennedy resisted the temptation to use preemptive airstrikes during the Cuban missile crisis because it would have violated international norms and undermined the U.S. reputation at home and abroad. In avoiding extrajudicial violence and finding a peaceful, multilateral solution, Kennedy and his Latin American partners strengthened the rule of law and defended their national and international security.

During the crisis, the U.S.’s neighbors in Latin America helped Kennedy take a step back from the brink and find a peaceful solution. That the world avoided nuclear war in 1962 was a triumph of multilateralism, rather than U.S. unilateralism.

Renata Keller received funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the American Philosophical Society.

Read These Next

Trump says climate change doesn’t endanger public health – evidence shows it does, from extreme heat

Climate change is making people sicker and more vulnerable to disease. Erasing the federal endangerment…

Citizenship voting requirement in SAVE America Act has no basis in the Constitution – and ignores pr

The House has passed a bill to require proof of citizenship for voting. Although it likely won’t become…

How the 9/11 terrorist attacks shaped ICE’s immigration strategy

The growth of today’s aggressive immigration tactics traces back 25 years, when enforcement took on…