When it comes to Ukraine peace negotiations, it’s all over the map

Donald Trump is reportedly ‘sick’ of being presented with maps of Ukraine’s battlefronts. The problem may be he and Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelenskyy are looking at different things.

Donald Trump is reportedly “sick” of seeing maps of the front line in Ukraine. Indeed, according to one European official’s account, he tossed aside Ukrainian delegation maps during his latest meeting with President Volodymyr Zelenskyy at the White House on Oct. 17, 2025.

Instead, Trump is said to have aggressively pushed Zelenskyy to accept Russia’s terms to end the war and surrender all of the Donbas region in Ukraine’s east to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

As a political geographer who has studied Eastern Europe and post-communist states, I know how crucial maps are to the dynamics of territorial conflicts and peace negotiations. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, for example, maps were central to the ethnic cleansing that took place in the early 1990s, driving visions of creating mono-ethnic space through violence, and also to the ending of the war. Similarly, in the Caucasus, cartographic fantasies of homogeneous territories have underwritten campaigns against ethnic others in Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Nagorno-Karabakh.

And it is no surprise that maps are a critical part of negotiations now to end the 3½-year conflict in Ukraine.

Creative cartography

Drawing partition lines on maps has always been a feature of stalemated territorial conflicts. U.S. negotiators in 1995 forged the agreement that brought Bosnia’s war to an end through last-minute cartographic adjustments ensuring that the settlement conformed to an already agreed-upon 49-51 percentage split of the territory between Bosnian-Serb forces and those representing the Bosnian Federation.

Dividing territory in percentage terms, however, goes against the grain of how most people view their territorial homelands. In his famous account of nations as “imagined communities,” the Anglo-Irish historian Benedict Anderson described how states create nations through the widespread circulation of a common territorial map. In this way, map images became a type of state logo. Nations not only imagined themselves as a community but as belonging to a particular recognizable space, a familiar territorial homeland.

Territories in today’s world have become instantly recognizable shapes on posters and T-shirts and in textbooks. Yet they are also experienced as something alive and personal – a “geo-body,” in the words of Thai historian Thongchai Winichakul.

It is part of what leads citizens, and nations, to feel deeply connected to their state’s territorial boundaries. And it helps explain the generally persistent resistance of Ukrainians to territorial concessions to Russia – even though there are signs that popular sentiment is beginning to shift after 3½ years of war.

Fighting and dying for a homeland, as Ukrainian soldiers have done in their thousands, adds to the emotive power of territory. To many Ukrainians it isn’t property they are being asked to concede but sacred and indivisible land paid for with blood.

This understanding of territory is quite different from that of Trump and his handpicked cadre of “deal guys” who treat international conflict like short-term business transactions.

Misreading the map

This pursuit of a deal over other considerations has a downside and can lead to missteps. Trump’s special envoy for peace missions, Steve Witkoff, believed he had achieved something of a breakthrough during a meeting with the Russians in early August when looking at areas where Russia might withdraw on the map. German newspaper Bild reported that Witkoff, who does not speak Russian and didn’t have his own translator, misunderstood Putin’s demand of a “peaceful withdrawal” of Ukrainians from Kherson and Zaporizhzhia as an offer of Russia’s “peaceful withdrawal” from those regions.

Because it led to the postponement of new U.S. sanctions and a summit proposal, the Russians went along with the misunderstanding, according to the Bild’s reporting.

Similarly, the subsequent Alaska summit was not the breakthrough Trump envisioned. Putin got the red-carpet treatment on U.S. soil but nonetheless subjected Trump to a lengthy historical lecture on why Russia owns Ukraine.

Putin was unwilling to give Trump the ceasefire deal the U.S. president desired. Putin did, however, make a territorial proposal that kept Trump interested in continuing to play the peacemaker: If Russia acquired all of the territory of the two oblasts that made up the Donbas, then Russia would consider freezing its lines in Zaporizhzhia and Kherson.

Haggling over percentiles

This provided the background for an extraordinary meeting in the White House on Aug. 18, 2025, when seven European leaders joined Zelenskyy in meeting Trump to discuss a possible endgame to the war.

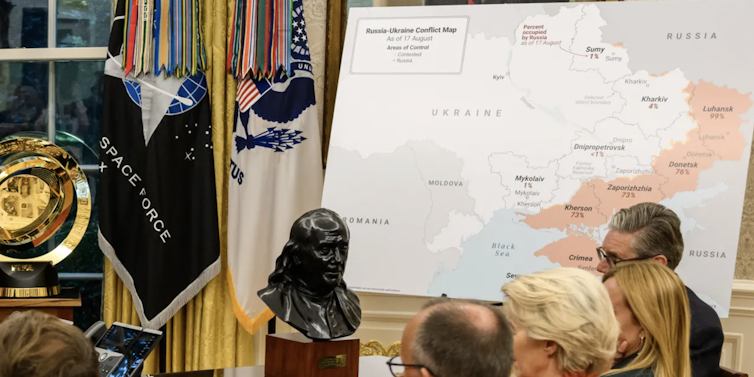

The Ukrainian delegation was pictured entering the White House with what looked like a rolled-up map. In the Oval Office, however, they were confronted with the White House’s own rigid board depicting a map of the “Russia-Ukraine Conflict.”

It featured a choropleth display with the estimated territory under Russian occupation colored in orange and quantified as a percentage figure of each oblast’s territory. The map indicated that Russia occupied 99% of Luhansk and 76% of Donetsk. Putin wanted 100% of both – a demand that required Ukraine to surrender the fortified territories safeguarding central Ukraine.

What the Oval Office map meant to Trump was clear the following day in a phone interview on “Fox and Friends.” Referring to the map, he said that a “big chunk of territory is taken,” implying it is now lost to Ukraine.

In other words, the map recorded the score in real estate terms from a regrettable war between a small state and a much larger one.

Zelenskyy tried to argue for a different approach to map issues, one that affirmed the symbolic and strategic importance of keeping Ukraine’s territorial integrity alive as an ideal for Ukrainians and the international community.

He made some progress. After meeting Zelenskyy at the United Nations on Sept. 23, Trump suggested that Ukraine could succeed in its fight to “take back their country in its original form.”

Battlegrounds as real estate

With Trump seemingly drifting toward supporting Ukraine with long-range missiles, Putin seized the initiative by phoning Trump. In an extensive phone call prior to Zelenskyy’s White House visit on Oct. 17, the Russian leader updated his offer for peace, suggesting his forces would withdraw from Zaporizhzhia and Kherson in return for all of the Donbas region.

This set the stage for the latest reported Trump-Zelenskyy shouting match and the tossing aside of front-line maps.

Afterward, Trump posted on social media: “… it is time to stop the killing, and make a DEAL! Enough blood has been shed, with property lines being defined by War and Guts. They should stop where they are.”

This is Trump’s current position on map issues. Backing off pressuring Ukraine to give up all the Donbas in public, he believes that Ukraine and the Donbas should be “cut up” along the current battlelines. Asked in a Fox News interview on Oct. 6 whether Putin would be open to ending the war “without taking significant property from Ukraine,” Trump responded: “Well, he’s going to take something. They fought and he has a lot of property. He’s won certain property.”

This gets at how Zelenskyy and Trump seemingly see different things when they look at front-line maps. The Ukrainian leader sees a painful reality, his country’s geo-body violently cut apart by an invading, occupying power. Trump comments indicate he sees it as a property dispute in which the strongest power has accumulated some territorial winnings and now needs to cash them in.

Gerard Toal in the past received funding from the US National Science Foundation and the Research Council of Norway.

Read These Next

The rise of ‘Merzoni’: How an alliance between Germany’s and Italy’s leaders is reshaping Europe

The center of gravity in Europe is increasingly aligning along a Rome-Berlin axis.

‘Proportional representation’ could reduce polarization in Congress and help more people feel like t

The electoral system used by many global democracies eliminates gerrymandering and has been shown to…

Why is US health care still the most expensive in the world after decades of cost-cutting initiative

To lower health care costs, the Trump administration will have to wrangle a complex system fraught with…