Xi’s show of unity with Putin and Kim could complicate China’s delicate diplomatic balance

China’s carefully staged display of unity with Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong Un at a parade marking China’s victory over Japan in WWII projected strength abroad, but it also risks unintended consequences.

If the purpose of a rare joint appearance of the leaders of Russia, North Korea and China on Sept. 3, 2025, was to foster unity among allies, then early indicators suggest its already working – just elsewhere.

Two days after the trio met in Beijing, Japan and Australia agreed to strengthen security cooperation in the Indo-Pacific region. Then on Sept. 11, an accord between Japan and the Philippines went into effect, allowing the armed forces of both nations to operate in each other’s territories. Such deals represent a show of unity by Pacific region countries against perceived Chinese assertiveness.

The placing of Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong Un at the side of President Xi Jinping at the high-profile commemorations marking the 80th anniversary of China’s victory over Japan in World War II was deliberate. Beijing was communicating solidarity and alignment among the three countries against the West. Western media outlets interpreted this moment as Beijing intended, warning of a new international order centered on China.

But as an expert in Northeast Asian security and China’s grand strategy, I believe the developments highlight a real danger to Beijing that its approach may be creating new challenges and risks. It hems Xi in strategically, forcing him closer to two unpredictable actors on China’s northeast borders while undermining any claims Beijing has to be an alternative, neutral global mediator. Above all else, it could further damage China’s fragile relations with Europe and countries in Asia.

And none of this will be to China’s benefit.

Xi’s awkward position on Ukraine

To be sure, China’s forging of closer ties with two states that much of the world sees as pariahs hasn’t come out of the blue. It follows years of increasing tensions between China and the West.

The war in Ukraine has been a main reason behind the recent deterioration of China–Europe relations, despite Beijing long claiming neutrality in the conflict and calling for peace talks.

Earlier this year, China signaled its dissatisfaction with Pyongyang for moving too close to Moscow and making military aid to Russia increasingly public.

Xi’s highly visible appearance alongside Putin and Kim now could undermine those positions and places the Chinese president in a somewhat awkward position: It gives the impression that Beijing acquiesces to the Russia–North Korea partnership and their war effort in Ukraine.

Pushing EU and US closer together

In Brussels, European Union foreign policy chief Kaja Kallas warned that the participation of Chinese, Russian, Iranian and North Korean leaders in Beijing’s parade represented an “authoritarian alliance” challenging the so-called rules-based international order.

Against this backdrop, China’s alignment with Russia and North Korea is only likely to deepen Europe’s security concerns and further strain already fraught China–EU economic relations.

It could push the EU to expand anti-dumping measures against China or accelerate efforts to reduce economic dependence on Beijing. And this could hurt China’s somewhat sluggish economy: In 2024, China was the European Union’s largest source of imports, with trade amounting to US$609 billion, while the EU stood as China’s second-largest export market.

Ironically, while U.S. President Donald Trump’s second-term policies – such as courting Putin and promoting an “America First” agenda – undermined the traditional transatlantic alliance, the growing China–Russia–North Korea alignment may have the opposite effect: driving Trump to embrace Europe and strengthen cooperation with its allies to counter the new bloc.

It was notable that on Sept. 4, a day after the Beijing parade, Trump urged European leaders to increase economic pressure on China and accused Beijing of financing Russia’s war in Ukraine. The European Commission was seemingly already minded to go this route, having recently announced that it is weighing whether to include several independent Chinese refineries in its latest round of sanctions against Russia.

Hardening stance in South Korea

The alignment of China, Russia and North Korea also risks promoting a trend Beijing has previously resisted: a China containment strategy forged through anti-Beijing alliances across the Pacific.

We already have a ramping up of U.S.-Philippines naval exercises, U.S.-Indonesia led multilateral exercises and now greater defense ties between Japan and the Philippines.

The Putin-Kim-Xi alliance is likely to push Japan and South Korea — both of which currently have relatively moderate stances toward China — to distance themselves from Beijing and further strengthen their alliances with the U.S. in order to counter this emerging bloc.

On Sept. 11, the U.S. and Japan began two weeks of military exercises featuring the Typhon intermediate-range missile system, capable of striking the Chinese mainland. And starting Sept. 15, South Korea, Japan and the U.S. will hold annual drills to bolster defenses against North Korea’s nuclear and missile threats.

Alliances aside, Chinese policy also risks hardening the domestic opinion and foreign policies of other nations against Beijing.

In South Korea, the ruling Democratic Party has, to date, favored a friendlier approach toward China and North Korea, while maintaining a cautious attitude toward its alliance with the U.S. and relations with Japan.

This stands in sharp contrast to the previous government of President Yoon Suk Yeol which pursued a hard-line stance on China and North Korea and actively sought to bolster trilateral cooperation with Washington and Tokyo.

Beijing’s embrace of North Korea now could force Seoul into reconsidering its China policy and revert to a more hostile stance.

China’s decision to invite Kim Jong-un – long isolated and sanctioned by the international community – to center stage in Beijing has widely been seen as tacit recognition of North Korea’s nuclear position.

Notably, during the Xi–Kim summit on Sept. 5, Beijing made no mention of denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula – a point that drew significant attention from South Korean media. It stood in contrast to the pair’s four previous meetings, in which both sides expressed support for the realization of the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.

Sino-Japanese relations

Japan finds itself in a similar position to South Korea.

Recently resigned Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba was considered a pro-China moderate within the ruling Liberal Democratic Party. Since taking office in October 2024, Ishiba’s approach marked a clear departure from that of his predecessor, Fumio Kishida, whose tough stance on Beijing had led to a sharp deterioration in Sino-Japanese relations.

Ishiba instead sought stability, meeting Xi at the APEC summit in Lima, Peru, in November 2024, where the two leaders agreed to work together to build a more stable and constructive partnership.

However, growing security concerns sparked by the China–Russia–North Korea alignment could well push Japan toward adopting a tougher China policy in the future.

How the show of unity in Beijing will play in Washington is an open question. Although Trump praised China’s parade as “beautiful” and “impressive,” he appeared displeased with the joint appearance of Xi, Putin and Kim, claiming on social media that their nations were “conspiring against” the United States.

A new international order?

Taken together, the Sept. 3 parade undeniably signaled Xi’s intent to build a new international order with China at the core. It projected a strong sense of deterrence toward the U.S. and the West, while also underscoring China’s dominant position within the trilateral relationship with Russia and North Korea.

Yet at the same time, I believe this high-profile alignment may carry risks: It deepens Western and regional suspicions of an “axis of upheaval,” threatens to further strain China’s foreign relations and is likely to accelerate balancing efforts against Beijing — most notably through closer transatlantic cooperation and a strengthening of the U.S.–Japan–South Korea alliance.

Linggong Kong does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

How a 22-year-old George Washington learned how to lead, from a series of mistakes in the Pennsylvan

Washington’s fundamental character as a military leader was forged in the Ohio River Valley, where…

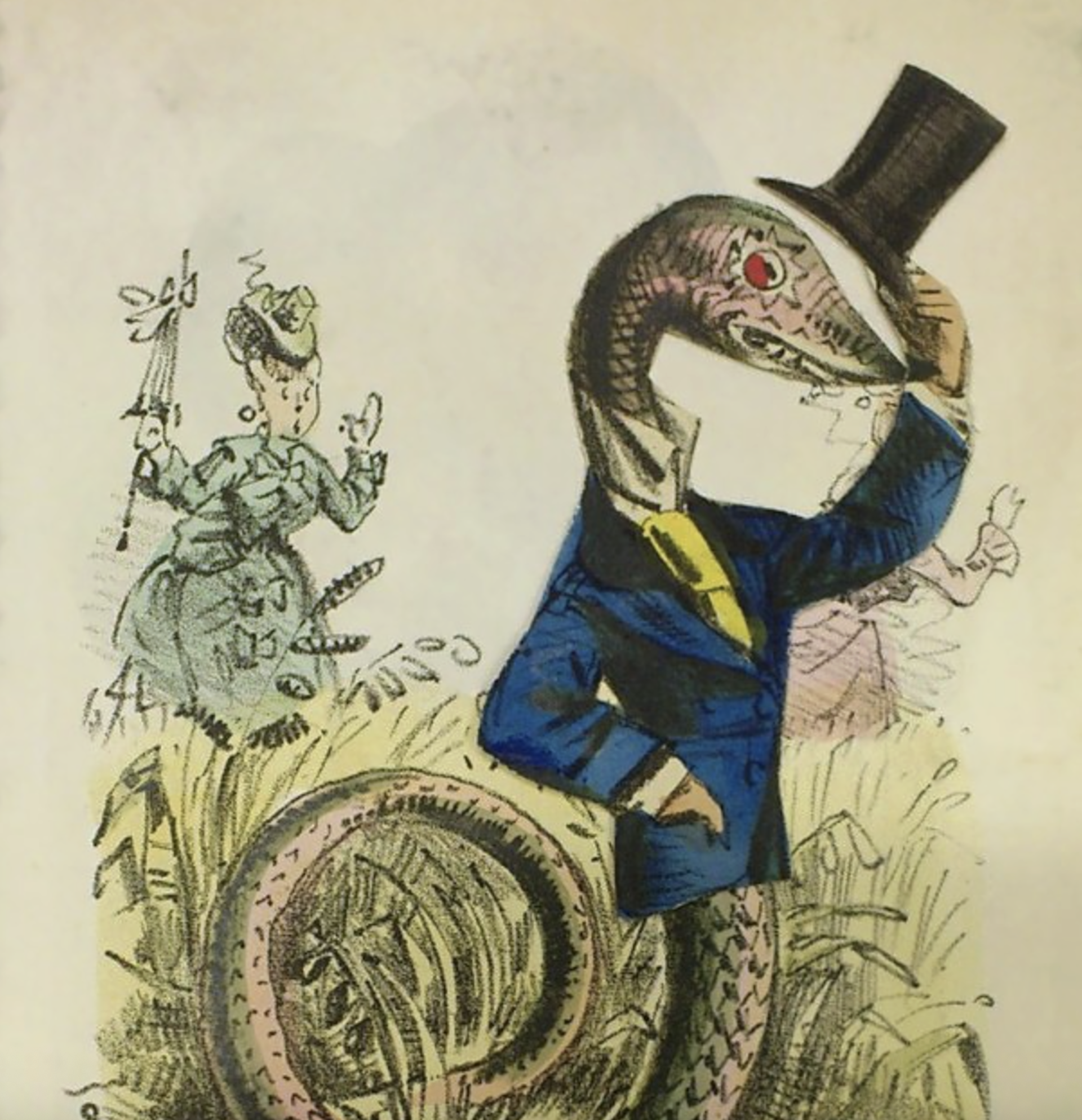

Valentine’s Day cards too sugary sweet for you? Return to the 19th-century custom of the spicy ‘vine

Victorians found a way to anonymously tell people they didn’t like exactly how they felt.

Infusing asphalt with plastic could help roads last longer and resist cracking under heat

A research team has paved plastic-infused roads in Texas and Bangladesh, with promising results.