When it comes to wars − from the Middle East to Ukraine − what we call them matters

Convention suggests wars are named after the participants or the place it which fighting takes place. But who chooses − and why?

Is the conflict in Eastern Europe a “special military operation in Ukraine” or a “Russian invasion”? And when it comes to events in the Middle East, are we talking about the “Israeli-Palestinian conflict,” the “War on Gaza” or the “Israel-Hamas war”?

As scholars who study international security, we know that how people refer to a war matters. The name may, for example, signal the speaker’s perspective on who is responsible for the fighting and, therefore, to blame for the death and destruction that follows.

We explored this idea as part of a recent analysis of how scholars discussed the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 compared with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. The results of our research show that scholars used diametrically opposed language in describing and referring to the two wars. While the vast majority described the conflict between Iraq and the U.S. as the “Iraq war” – referencing just one of the participants – the most common ways of referring to the current conflict in Eastern Europe are variations of the “Russia-Ukraine War” – which includes both participants.

This sparked our interest into delving deeper into war-naming conventions. What we found is that the way wars are referred to in the U.S. – by politician, journalists and in public scholarship – tends to serve state interests and power rather than necessarily reflect the realities of conflicts.

War-naming conventions

There are a number of different ways in which wars are named, but they can be broadly grouped around place, participants or time.

In the first category, you have examples ranging from the “Vietnam War” to the “Falklands War.” Both examples, incidentally, highlight the fact that a war’s name may differ from place to place. The Vietnam War is the “American War” to the Vietnamese, and Argentinians talk of the “War of the Malvinas.”

In the second category are conflicts such as the “Spanish-American War,” the “Franco-Prussian War” and the “Sino-Japanese War” of 1894–1895. These are also subject to some variation, known in France and China as the “War of 1870” and the “Jiawu war,” respectively.

Wars are named after other conventions, too. They can be named after significant factors that make them stand out – examples include holidays in which the conflict took place in the case of the “Yom Kippur War” – or how long they last, such as the “Thirty Years’ War.”

At first look, naming wars after their location, participants, starting date or duration might appear to be an exercise in objective detachment. But examining why one naming convention is used over another can reveal a particular perspective or bias.

Historian Danny Keenan has demonstrated how decisions are made in naming wars that may imply culpability among the actors involved. He notes that what has come to be known as the “New Zealand Wars” was once referred to as “The Māori Wars.”

“It was generally acknowledged that Māori should not bear such responsibility” implied by the earlier name, writes Keenan.

The New Zealand/Māori Wars name change gets at a wider point that naming conflicts after one participant can be problematic, especially when there is a power imbalance.

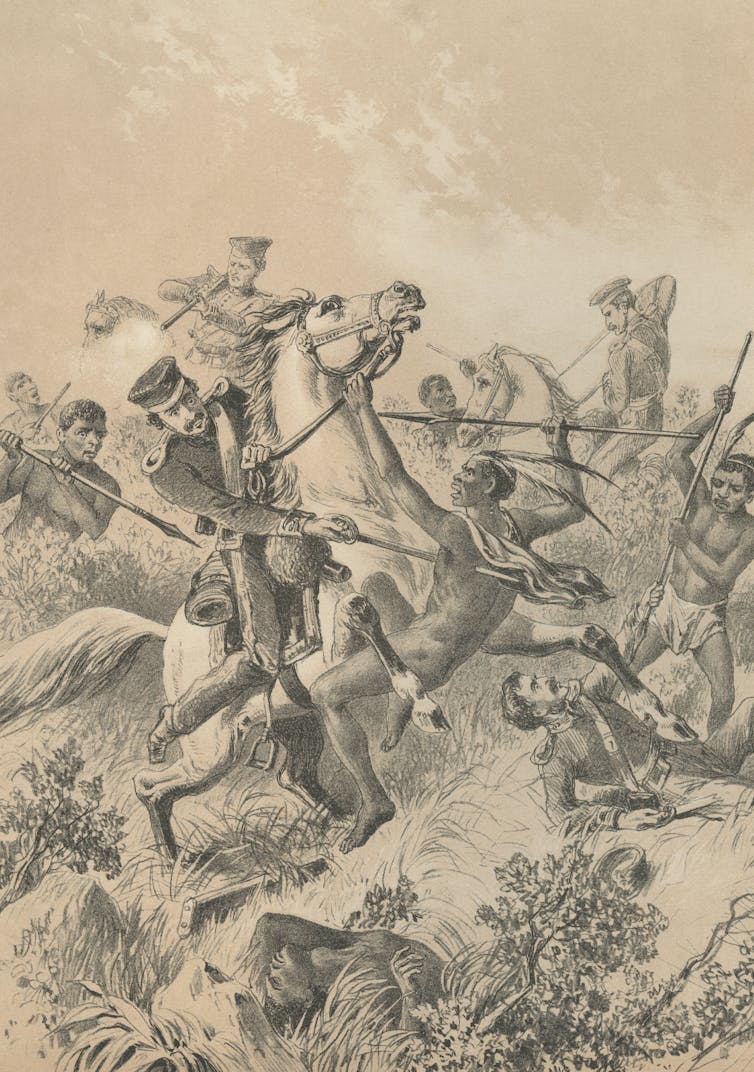

Take the British naming of their colonial wars after the populations they were subjugating, such as the “Xhosa Wars” or the “Mahdist War.” Naming an interstate war based on the state in which the war is fought – while omitting the name of outside instigators – implies the culpability of that state.

And more powerful actors, such as colonial powers, have historically been able to make their chosen name stick, obscuring their role in the violence.

When apparent objectivity belies bias

While naming wars after both participants seemingly avoids these biases, what becomes evident is that the order in which participants are listed matters. For example, the “Philippine-American War” – fought between 1899-1902 – may imply that the U.S. engaged in that conflict only in response to the actions of an antagonist, even though it was the U.S. that was seeking to deny the Philippines independence.

The results of our research into the U.S.’s and Russia’s respective invasions of Iraq and Ukraine demonstrate how different naming conventions are used politically.

“Iraq war,” we argue, suggests full culpability on Iraq for the war being fought on its territory, despite Iraq having not attacked the U.S. or its allies. It also entirely omits the U.S., even though it was the invading force.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, meanwhile, is referred to by public scholars and media in a variety of ways that emphasize Russia or President Vladimir Putin as an aggressive antagonist. Examples include Russia’s “murderous war on Ukraine”; “Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine”; and “Russian war against Ukraine.”

The New York Times and Foreign Policy Magazine include articles about the war under the topic heading “Russia-Ukraine War,” and The Washington Post and the magazine Foreign Affairs do so under “War in Ukraine.”

Although “War in Ukraine” employs the location naming convention, the other headlines and topic headings use the participants convention, leading with Russia as the antagonist. Noticeably absent is any reference to the “Ukraine War.”

What to call the Middle East conflict?

The naming of the current conflict in the Middle East presents its own issues.

The New York Times and Foreign Affairs, both of which we analyzed for our research, as well as other U.S.-based popular news media such as USA Today and Detroit Free Press, all headline their coverage of Gaza and Israel with the “Israel-Hamas War.”

Based on what research tells us regarding naming conventions, what might this tell us?

First, consider the placement of Israel first. This could identify Israel as the aggressor. However, the use of “Hamas” over “Gaza” is noteworthy. Hamas is recognized by the U.S. and most of the Western world as a terrorist organization. As such, placing Israel first actually can be understood as a legitimation of Israel’s violence.

Also, their is no mention of Palestine, Palestinians, Gaza or Gazans.

This is despite Israeli actions long superseding the targeting of Hamas. Israel’s plans now include the full occupation of, at least, large parts of Gaza and the potential displacement of Gaza’s people.

The move away from the use of “Palestinian” cannot, we argue, be assumed to be incidental. Since October 2023, mentions of the “Israeli-Palestinian” conflict have seemingly become rarer, despite the growing, and related, violence in the West Bank and Jerusalem.

Finally, the use of the term “war” in referring to the “Israeli-Hamas war” can itself be problematic as it indicates a certain level of symmetry.

In the current conflict in Gaza, that is not the case: Israel possesses a far superior and advanced military. And since the Hamas attack on Oct. 7, 2023, in which 1,200 Israelis were killed, those killed have nearly entirely been Palestinians – over 63,000 as of September 2025.

The difference in size and capability between Israel’s military and Hamas is such that using the term “war” is, we believe, misleading.

It may be more accurate to describe it as an “occupation” or “a noninternational armed conflict.” A growing number of international bodies are calling it a “genocide.”

Challenging war narratives

How media, scholars and politicians refer to specific wars says a lot about how they would like them to be perceived. It is not coincidence, we argue, that wars and violence perpetrated by the U.S. and its allies are typically named in ways that contribute to a beneficial narrative, while the opposite is true when those deemed U.S. enemies are involved.

Repetition of such names for war and violence can reinforce narratives that serve state interests – it makes sense, therefore, for state officials to propagate names that potentially misinform. When news media and experts do the same, however, it undermines society’s ability to substantially challenge dominant framings in times of war.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Historically Black colleges and universities do more than offer Black youths a pathway to opportunit

HBCUs make up just 3% of the country’s colleges and universities. But their graduates include 40%…

How a 22-year-old George Washington learned how to lead, from a series of mistakes in the Pennsylvan

Washington’s fundamental character as a military leader was forged in the Ohio River Valley, where…

Local governments provide proof that polarization is not inevitable

Partisan debates are less heated at the local level, providing lessons that might help calm the waters…