US obliteration of Caribbean boat was a clear violation of international ‘right to life’ laws – no m

An expert in international law explains that the Trump administration’s justification for deadly strike doesn’t hold water.

The U.S. government is justifying its lethal destruction of a boat suspected of transporting illegal drugs in the Caribbean as an attack on “narco-terrorists.”

But as an expert on international law, I know that line of argument goes nowhere. Even if, as the U.S. claims, the 11 people killed in the Sept. 2, 2025, U.S. Naval strike were members of the Tren de Aragua gang, it would make no difference under the laws that govern the use of force by state actors.

Nor does the fact that protests from other nations in the region are unlikely, due in large part to Washington’s diplomatic and economic power – and President Donald Trump’s willingness to wield it.

Protest is not what proves the law. Unlawful killing is unlawful regardless of who does it, why, or the reaction to it. And in regard to the U.S. strike on the alleged Venezuelan drug boat, the deaths were unlawful.

Domestic U.S. legal issues aside – and concerns have been raised on those grounds, too – the killings in the Caribbean violated the human right to life, an ancient principle codified today in leading human rights treaties.

Killing in war and peacetime

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights is one such treaty to which the United States is a party. Article 6 of the covenant holds: “Every human being has the inherent right to life. This right shall be protected by law. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his life.”

Through rulings of human rights and other courts, it has been well established that determining when a killing has been arbitrary depends on whether the killing occurred in the context of peace or armed conflict.

Peace is the norm. And in times of peace, government agents are only permitted to use lethal force to save a life immediately. The United Nations’ Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials reinforce this peacetime right-to-life standard, noting “intentional lethal use of firearms may only be made when strictly unavoidable in order to protect life.”

The principle is also supported by the fact the U.S. has bilateral treaties regarding cooperation in drug interdiction. The Coast Guard has a series of successful Maritime Law Enforcement Agreements – known as Shiprider Agreements – with nations in the Caribbean and elsewhere. They commit U.S. authorities to respecting fundamental due process rights of criminal suspects. Such rights obviously do not include summary execution at sea.

Bypassing these bilateral and international treaties to dramatically blow up a ship not only violates law, but it will, I believe, further undermine trust and confidence in these or any other agreements the U.S. makes.

Flouting international law

In armed conflict, intentionally targeting an enemy vessel with lethal force is permitted, so long as the attack complies with international humanitarian law.

But it would be very difficult, in my opinion, for the U.S. to argue that it took action in the context of an armed conflict. In international law, armed conflict exists when two or more organized armed groups engage in intense fighting lasting at least a day. The U.S. started ignoring the definition of armed conflict when it began targeted killings of terrorism suspects with drones and other military means in 2002. War was raging in Afghanistan, but I would argue that killings in Yemen and elsewhere were not sufficiently tied to the fighting there to be lawful. The killings in Caribbean on Sept. 2 are a worse violation – they had links to no hostilities.

Organized crime groups of the kind the Trump administration alleges the boat members belonged to may be highly violent, but they are not engaged in armed conflict.

And while some armed groups waging war against governments do deal in drugs to pay for their participation in conflict, there is no evidence the gang that President Donald Trump purportedly targeted is such a group.

The term the Trump administration has used for the group is “narco-terrorist.” But that is not a recognized term under international law. As such, using it creates no exception to established principles on the right to life.

Nor does the right to life change depending on whether killings took place in territorial waters or on the high seas.

Given that the U.S. likely flouted international law, one could be forgiven for expecting the Trump administration to be held to account by the mechanisms that support the complex and comprehensive international legal system, such as the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Court.

But prosecuting alleged violations of international law is notoriously hard. And given the power of the U.S. government and the nature of the victims – members of an alleged drugs gang – the political will to hold Washington to account may be weak. Yet, the attack still presents an important opportunity to demand respect for international law and what it stipulates in regard to the right to life.

Mary Ellen O'Connell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

How a 22-year-old George Washington learned how to lead, from a series of mistakes in the Pennsylvan

Washington’s fundamental character as a military leader was forged in the Ohio River Valley, where…

Mapping cemeteries for class – how students used phones and drones to help a city count its headston

Cemeteries are a treasure trove of local history and family connection. Technology and ingenuity have…

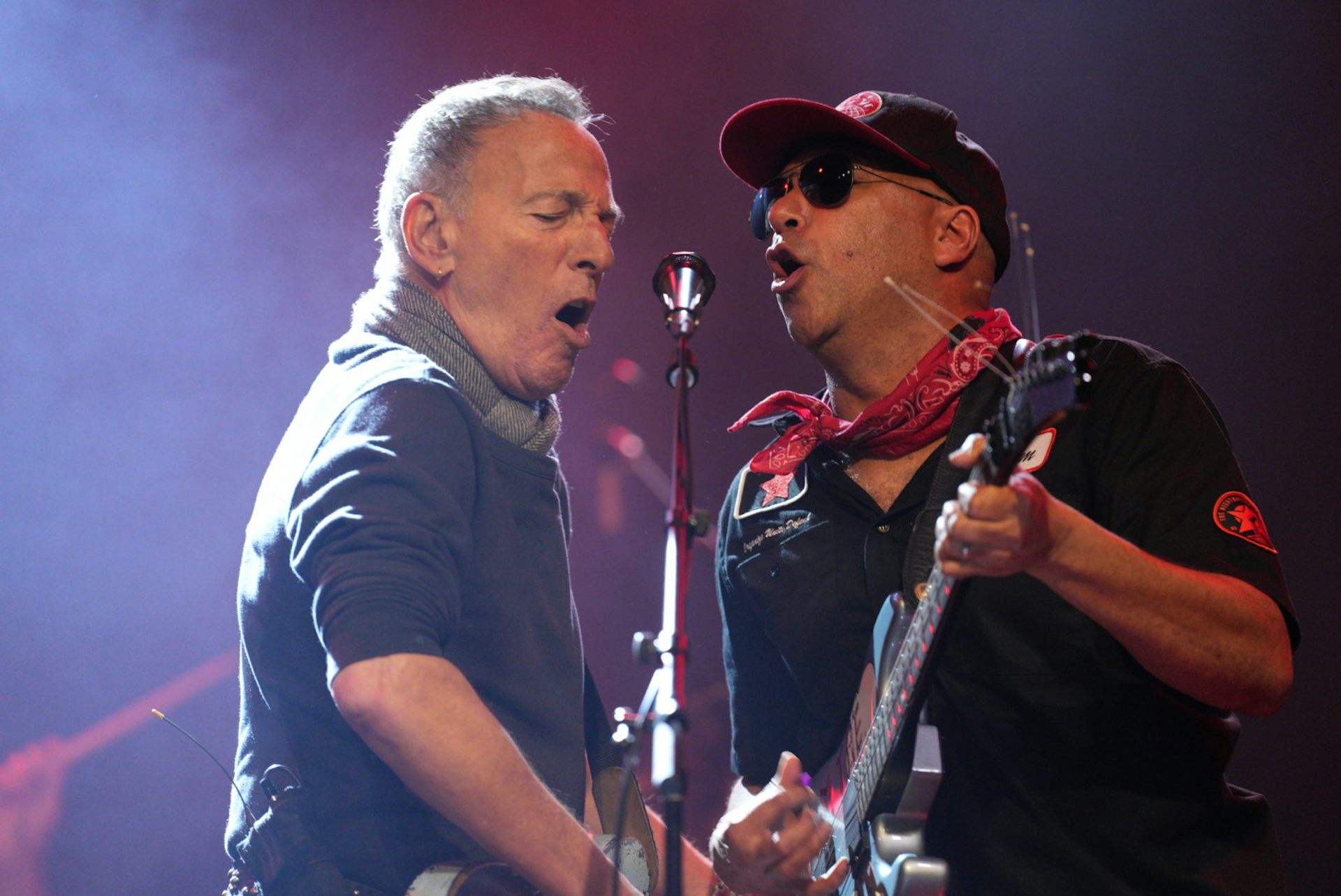

‘Which Side Are You On?’: American protest songs have emboldened social movements for generations, f

Bruce Springsteen wrote and recorded ‘Streets of Minneapolis’ within days of Alex Pretti’s killing,…