Here’s a way to save lives, curb traffic jams and make commutes faster and easier − ban left turns a

Even though research supports the change, most cities have been slow to ban left turns at even the most congested intersections.

More than 60% of traffic collisions at intersections involve left turns. Some U.S. cities – including San Francisco, Salt Lake City and Birmingham, Alabama – are restricting left turns.

Dr. Vikash Gayah, a professor of civil engineering at Penn State University and the interim director of the Larson Transportation Institute, discusses how left turns at intersections cause accidents, make traffic worse and use more gas.

The Conversation has collaborated with SciLine to bring you highlights from the discussion, edited for brevity and clarity.

How dangerous are left turns at intersections?

Vikash Gayah: When you make a left turn, you have to cross oncoming traffic. When you have a green light, you need to wait for a gap in the oncoming traffic before turning left. If you misjudge when you decide to turn, you could hit the oncoming traffic, or be hit by it. That’s an angle crash, one of the most dangerous types of crashes.

Also, the driver of the left-turning vehicle is typically looking at oncoming traffic. But pedestrians may be crossing the street they’re turning on to. Often the driver doesn’t see the pedestrians, and that too can cause a serious accident.

On the other hand, right turns require merging into traffic, but they’re not conflicting directly with traffic. So right turns are much, much safer than left turns.

What are the statistics on the unique dangers of left turns?

Gayah: Approximately 40% of all crashes occur at intersections − 50% of those crashes involve a serious injury, and 20% involve a fatality.

About 61% of the crashes at intersections involve a left turn. Left-hand turns are generally the least frequent movement at an intersection, so that 61% is a lot.

Why are left turns inefficient for traffic flow?

Gayah: When left-turning vehicles are waiting for the gap, they can block other lanes from moving, particularly when several vehicles are waiting to turn left.

Instead of the solid green light, many intersections use the green arrow to let left-turning vehicles move. But to do that, all other movements at the intersection have to stop. Stopping all other traffic just to serve a few left turns makes the intersection less efficient.

Also, every time you move to another “phase” of traffic – like the green arrow – the intersection has a brief period of time when all the lights are red. Traffic engineers call that an all-red time, and that’s when the intersection is not serving any vehicles. All-red time is two to three seconds per phase change, and that wasted time adds up quickly to further make the intersection less efficient.

What restrictions have been tried in different cities?

Gayah: When a downtown is not very busy – in the off-peak periods – allowing left turns is fine because you don’t need that additional ability to move vehicles at each intersection.

Some cities are implementing signs that say no left turns at intersections from 7 to 9, which is the morning peak period, or 4 to 6, which is the afternoon peak period. In San Francisco, for example, Van Ness Avenue restricts left turns during peak periods.

But cities aren’t implementing these restrictions on a larger scale. Restrictions are more along individual corridors or isolated intersections instead of essentially the entire downtown, where possible. That would make the downtown street network more efficient.

Roundabouts are one approach to avoiding left turns.

Gayah: Roundabouts are safe because there’s no longer a need to cross opposing traffic. Everyone circulates in the same direction. You find where you need to go and then exit.

But restricting left turns, in general, is more efficient. Roundabouts aren’t as efficient when it’s busier. The roundabout gets full, which can cause a gridlock, and no vehicle can move. Traditional intersections are less prone to gridlock.

Roundabouts also take up more space. Installing a roundabout might mean expanding the intersection. In some downtowns, that means tearing down buildings or removing sidewalks. Restricting left turns only requires a sign that says “no left turns” or “no left turns during peak periods.” That’s it.

What are the benefits to banning left turns in urban areas?

Gayah: Any way you cut it, eliminating left turns will result in longer travel distances. I’ll have to travel a longer distance to get to where I need to go. The worst case is having to circle the block. I’m actually traveling four extra block lengths to get to where I need to go.

But not all trips require circling the block. In a typical downtown, each trip will be about one block length longer on average. That’s not a lot of extra distance. And that extra driving is more than offset by the fact that each intersection with banned left turns is now moving more vehicles. Which means every time you’re at an intersection, you wait less time, on average. So you travel a slightly longer distance but get to where you’re going more quickly.

Does avoiding left turns improve fuel efficiency?

Gayah: Our research found that even though vehicles travel longer distances on average with the restricted left turns, they spend less fuel – about 10% to 15% less per trip – because they don’t stop as much at intersections.

This is why UPS and other fleets route their vehicles to avoid left turns. There’s less idling and fewer stops.

Do you think banning left turns could become widely accepted?

Gayah: It’s a new strategy, so it’s uncomfortable for some people. But when they get to their destination faster, I think people will latch onto it.

Watch the full interview to hear more.

SciLine is a free service based at the American Association for the Advancement of Science, a nonprofit that helps journalists include scientific evidence and experts in their news stories.

Vikash V. Gayah's research has been funded by various State Departments of Transportation (including Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Washington State, Montana, South Dakota and North Carolina), US Department of Transportation (via the Mineta National Transit Research Consortium, the Mid-Atlantic Universities Transportation Center, and the Center for Integrated Asset Management for Multimodal Transportation Infrastructure Systems), Federal Highway Administration, National Cooperative Highway Research Program, and National Science Foundation..

Read These Next

Held captive in their own country during World War II, Japanese Americans used nature to cope with t

Incarcerated in rough barracks surrounded by barbed wire and armed soldiers, Japanese Americans made…

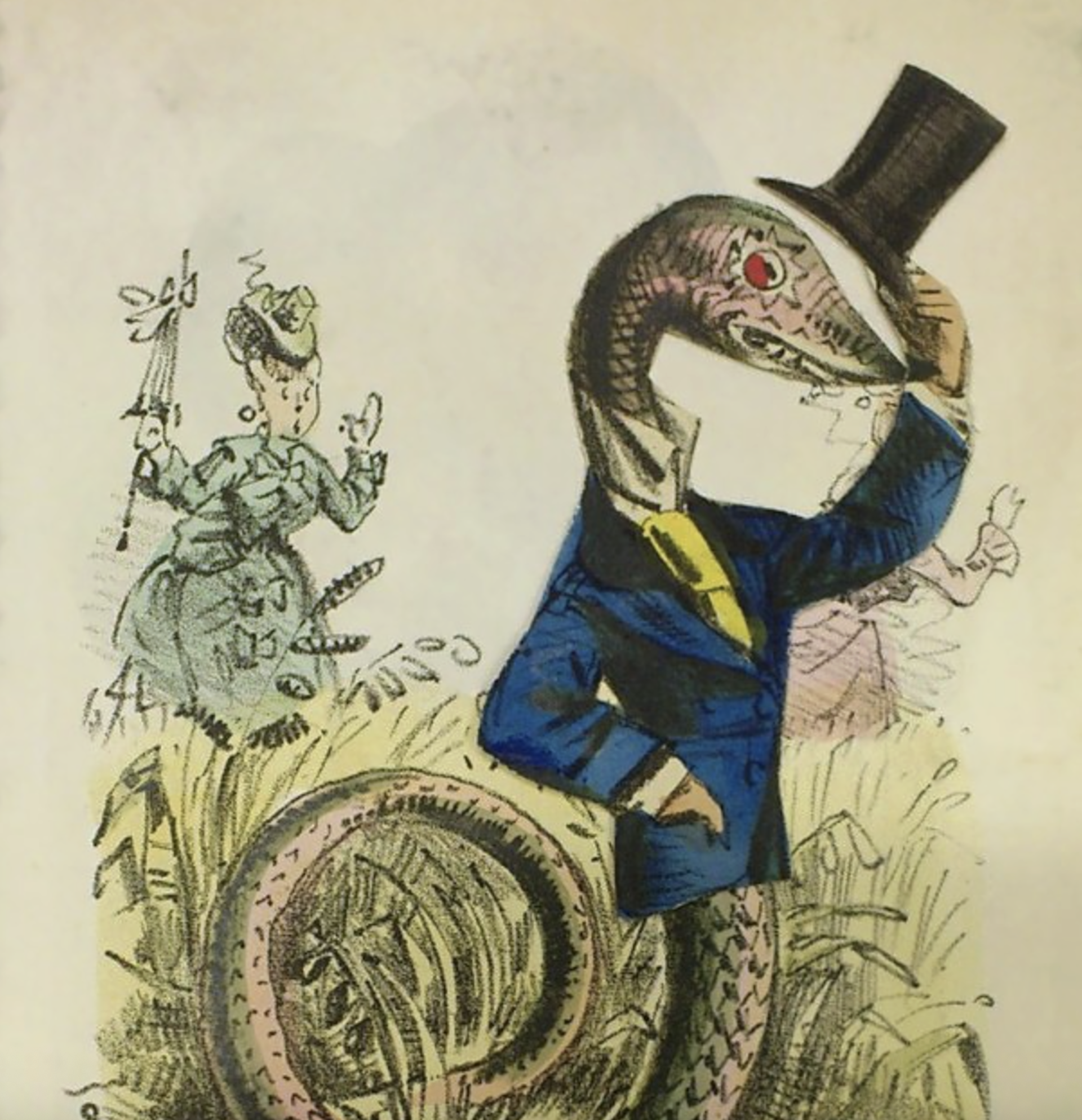

Valentine’s Day cards too sugary sweet for you? Return to the 19th-century custom of the spicy ‘vine

Victorians found a way to anonymously tell people they didn’t like exactly how they felt.

How do scientists hunt for dark matter? A physicist explains why the mysterious substance is so hard

Dark matter doesn’t seem to interact with the matter we can see and touch, so scientists look for…