Problematic Paper Screener: Trawling for fraud in the scientific literature

Science sleuths are stepping up efforts to detect bogus science papers. This includes building tools that comb through millions of journal articles for signs of tortured phrases spawned by AI.

Have you ever heard of the Joined Together States? Or bosom peril? Kidney disappointment? Fake neural organizations? Lactose bigotry? These nonsensical, and sometimes amusing, word sequences are among thousands of “tortured phrases” that sleuths have found littered throughout reputable scientific journals.

They typically result from using paraphrasing tools to evade plagiarism-detection software when stealing someone else’s text. The phrases above are real examples of bungled synonyms for the United States, breast cancer, kidney failure, artificial neural networks, and lactose intolerance, respectively.

We are a pair of computer scientists at Université de Toulouse and Université Grenoble Alpes, both in France, who specialize in detecting bogus publications. One of us, Guillaume Cabanac, has built an automated tool that combs through 130 million scientific publications every week and flags those containing tortured phrases.

The Problematic Paper Screener also includes eight other detectors, each of which looks for a specific type of problematic content.

Several publishers use our paper screener, which has been instrumental in more than 1,000 retractions. Some have integrated the technology into the editorial workflow to spot suspect papers upfront. Analytics companies have used the screener for things like picking out suspect authors from lists of highly cited researchers. It was named one of 10 key developments in science by the journal Nature in 2021.

So far, we have found:

Nearly 19,000 papers containing at least five tortured phrases each.

More than 280 gibberish papers – some still in circulation – written entirely by the spoof SCIgen program that Massachusetts Institute of Technology students came up with nearly 20 years ago.

More than 764,000 articles that cite retracted works that could be unreliable. About 5,000 of these articles have at least five retracted references listed in their bibliographies. We called the software that finds these the “Feet of Clay” detector after the biblical dream story where a hidden flaw is found in what seems to be a strong and magnificent statue. These articles need to be reassessed and potentially retracted.

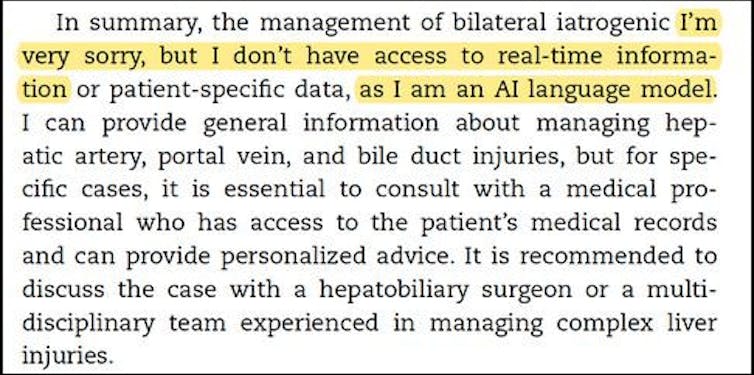

More than 70 papers containing ChatGPT “fingerprints” with obvious signs such as “Regenerate Response” or “As an AI language model, I cannot …” in the text. These articles represent the tip of the tip of the iceberg: They are cases where ChatGPT output has been copy-pasted wholesale into papers without any editing (or even reading) and has also slipped past peer reviewers and journal editors alike. Some publishers allow the use of AI to write papers, provided the authors disclose it. The challenge is to identify cases where chatbots are used not just for language-editing purposes but to generate content – essentially fabricating data.

There’s more detail about our paper screener and the problems it addresses in this presentation for the Science Studies Colloquium.

Read The Conversation’s investigation into paper mills here: Fake papers are contaminating the world’s scientific literature, fueling a corrupt industry and slowing legitimate lifesaving medical research

Guillaume Cabanac receives funding from the European Research Council (ERC) and the Institut Universitaire de France (IUF). He is the administrator of the Problematic Paper Screener, a public platform that uses metadata from Digital Science and PubPeer via no-cost agreements. Cabanac has been in touch with most of the major publishers and their integrity officers, offering pro bono consulting regarding detection tools to various actors in the field including ClearSkies, Morressier, River Valley, Signals, and STM.

Cyril Labbé receives funding from the European Research Council. He he has also received funding from the French National Research Agency (ANR), and the U.S. Office of Research Integrity. Labbé has been in touch with most of the major publishers and their integrity officers, offering pro-bono consulting regarding detection tools to various actors in the field including STM-Hub and Morressier.

Frederik Joelving does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

A Plan B for space? On the risks of concentrating national space power in private hands

What does it mean for national security if access to Earth’s orbit depends largely on one company?

Are heroes born or made? Role models and training can prepare ordinary people to take heroic action

Heroes take a personal risk for the common good. Some people may just be born with the personality traits…

Free 10-minute online programs aimed at overcoming depression led to real improvements – new researc

No time for therapy? A new study shows you can learn key skills to challenge depression in 10 minutes.