That Arctic blast can feel brutally cold, but how much colder than ‘normal’ is it really?

The answer depends on how you define ‘normal.’ The baseline has been creeping up as the planet warms.

An Arctic blast hitting the central and eastern U.S. in early January 2025 is creating fiercely cold conditions in many places. Parts of North Dakota dipped to more than 20 degrees below zero, and people as far south as Texas woke up on Jan. 6 to temperatures in the teens. A snow and ice storm across the middle of the country added to the winter chill.

Forecasters warned that temperatures could be “10 to more than 30 degrees below normal” across much of the eastern two-thirds of the country during the first full week of the year.

But what does “normal” actually mean?

While temperature forecasts are important to help people stay safe, the comparison to “normal” can be quite misleading. That’s because what qualifies as normal in forecasts has been changing rapidly over the years as the planet warms.

Defining normal

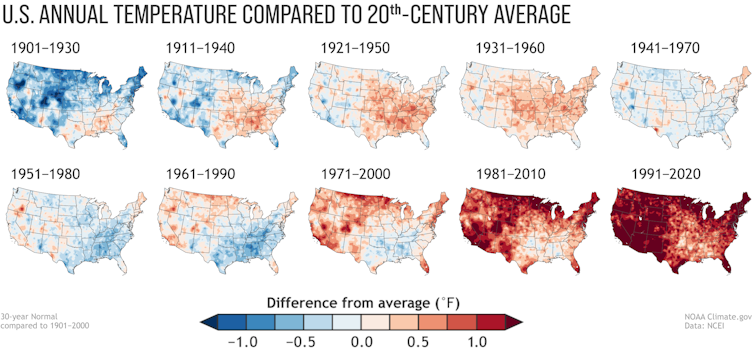

One of the most used standards for defining a science-based “normal” is a 30-year average of temperature and precipitation. Every 10 years, the National Center for Environmental Information updates these “normals,” most recently in 2021. The current span considered “normal” is 1991-2020. Five years ago, it was 1981-2010.

But temperatures have been rising over the past century, and the trend has accelerated since about 1980. This warming is fueled by the mining and burning of fossil fuels that increase carbon dioxide and methane in the atmosphere. These greenhouse gases trap heat close to the planet’s surface, leading to increasing temperature.

Because global temperatures are warming, what’s considered normal is warming, too.

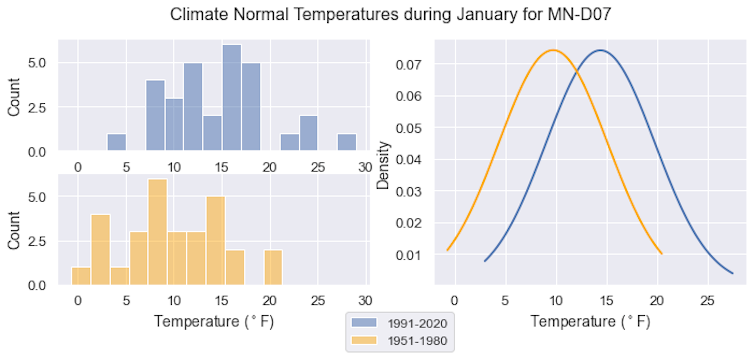

So, when a 2025 cold snap is reported as the difference between the actual temperature and “normal,” it will appear to be colder and more extreme than if it were compared to an earlier 30-year average.

Thirty years is a significant portion of a human life. For people under age 40 or so, the use of the most recent averaging span might fit with what they have experienced.

But it doesn’t speak to how much the Earth has warmed.

How cold snaps today compare to the past

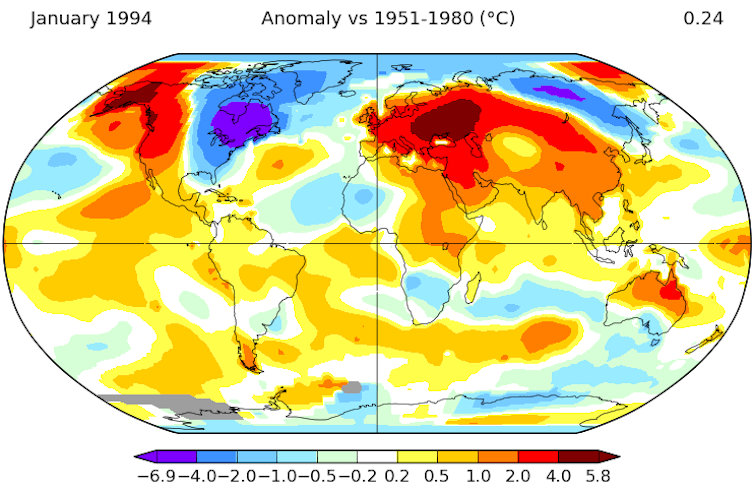

To see how today’s cold snaps – or today’s warming – compare to a time before global warming began to accelerate, NASA scientists use 1951-1980 as a baseline.

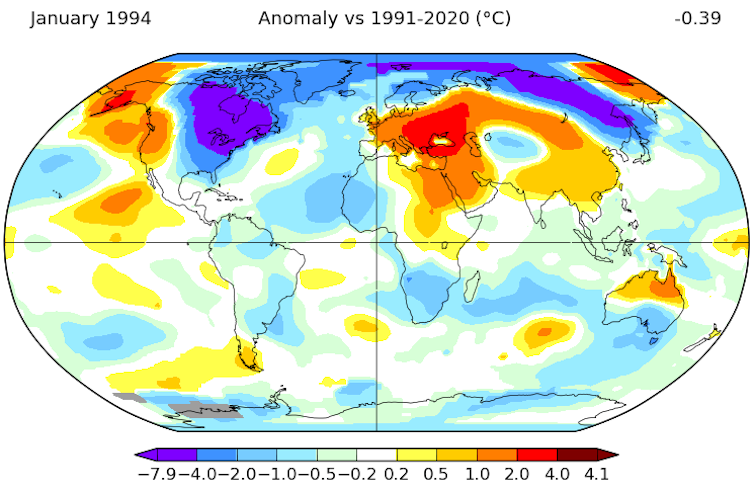

The reason becomes evident when you compare maps.

For example, January 1994 was brutally cold east of the Rocky Mountains. If we compare those 1994 temperatures to today’s “normal” – the 1991-2020 period – the U.S. looks a lot like maps of early January 2025’s temperatures: Large parts of the Midwest and eastern U.S. were more than 7 degrees Fahrenheit (4 degrees Celsius) below “normal,” and some areas were much colder.

But if we compare January 1994 to the 1951-1980 baseline instead, that cold spot in the eastern U.S. isn’t quite as large or extreme.

Where the temperatures in some parts of the country in January 1994 approached 14.2 F (7.9 C) colder than normal when compared to the 1991-2020 average, they only approached 12.4 F (6.9 C) colder than the 1951-1980 average.

As a measure of a changing climate, updating the average 30-year baseline every decade makes warming appear smaller than it is, and it makes cold snaps seem more extreme.

Conditions for heavy lake-effect snow

The U.S. will continue to see cold air outbreaks in winter, but as the Arctic and the rest of the planet warm, the most frigid temperatures of the past will become less common.

That warming trend helps set up a remarkable situation in the Great Lakes that we’re seeing in January 2025: heavy lake-effect snow across a large area.

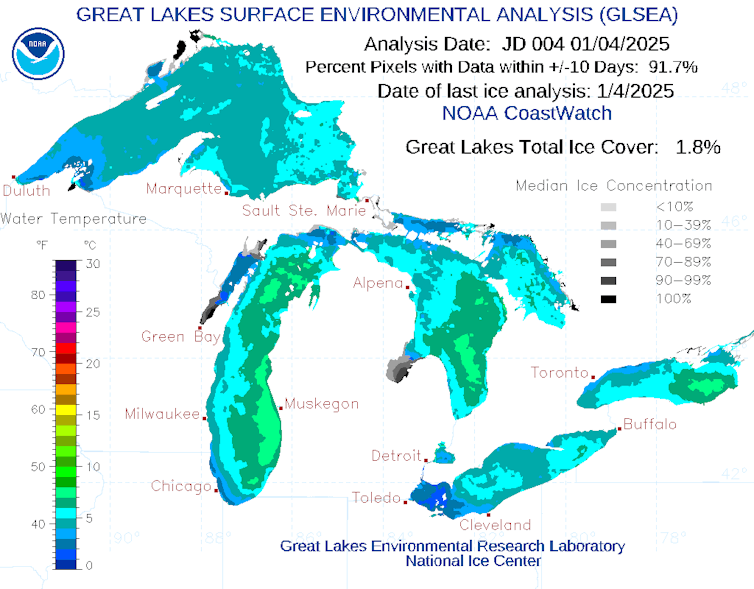

As cold Arctic air encroached from the north in January, it encountered a Great Lakes basin where the water temperature was still above 40 F (4.4 C) in many places. Ice covered less than 2% of the lakes’ surface on Jan. 4.

That cold dry air over warmer open water causes evaporation, providing moisture for lake-effect snow. Parts of New York and Ohio along the lakes saw well over a foot of snow in the span of a few days.

The accumulation of heat in the Great Lakes, observed year after year, is leading to fundamental changes in winter weather and the winter economy in the states bordering the lakes.

It’s also a reminder of the persistent and growing presence of global warming, even in the midst of a cold air outbreak.

Richard B. (Ricky) Rood receives funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Read These Next

Winter Olympians often compete in freezing temperatures – physiology and advances in materials scien

While physical exertion helps athletes stay warm, sweating can lead to dehydration.

Whether it’s yoga, rock climbing or Dungeons & Dragons, taking leisure to a high level can be good f

When a hobby becomes something larger, with a focus on improving skills and developing deep knowledge,…

US experiencing largest measles outbreak since 2000 – 5 essential reads on the risks, what to do and

Public health scholars worry that the resurgence of measles may signal a coming wave of other vaccine-preventable…