Syrians rejoice in a new beginning, after 54 years of tyranny

The Syrian revolution is profoundly significant to those who suffered suffocating repression, surveillance and everyday indignities under a brutal dictator.

Millions of Syrians are feeling hope for the first time in years.

The authoritarian regime of Bashar al-Assad fell on Dec. 8, 2024, after a 12-day rebel offensive.

Most commentaries on this stunning reversal of a conflict seemingly frozen since 2020 emphasize shifts in geopolitics and balance of power. Some analysts trace how Assad’s main backers – Iran, Hezbollah and Russia – became too weakened or preoccupied to come to his aid as in the past. Other commentators consider how rebels prepared and professionalized, while the regime decayed, leading to the latter’s collapse.

These factors help explain the speed and timing of the collapse of one of the Middle East’s longest and most brutal dictatorships. But these factors should not overshadow the human significance of Assad’s overthrow.

Assad’s fall in its revolutionary context

During the past two weeks, Syrians have rejoiced as symbols of Assad domination came down and the revolutionary flag went up. They held their breath as rebels freed captives from the regime’s notorious prisons. They shed tears as displaced people returned and families reunited after years of separation.

And then, finally, Syrians around the world poured into the streets to celebrate the end of 54 years of tyranny.

To appreciate the magnitude of this achievement requires historical context, one that I have documented in two books based on interviews with more than 500 Syrian refugees over the past 12 years.

My first book begins with stories of the suffocating repression, surveillance and indignities that characterized everyday life in the single-party security state that Hafez al-Assad established in 1970, and his son Bashar inherited in the year 2000.

It conveys tentative optimism as uprisings spread across the Arab world in 2011, blooming into exhilaration when millions of Syrians broke the barrier of fear and risked their lives to demand political change.

Syrians described participating in protest as the first time they breathed or felt like a citizen. One man told me that it was better than his wedding day. A woman referred to it as the first time she ever heard her own voice. “And I told myself that I would never let anyone steal my voice again,” she added.

It was not only the feeling of freedom that was unprecedented but also the feelings of solidarity as strangers worked together, of pride as people cultivated the talents and capacities necessary to sustain revolution, and, most of all, of hope that Syrians could reclaim their country and determine their own fate.

“We started to get to know each other,” an activist recalled of those heady days. “People discovered that they were photographers or journalists or filmmakers. We were changing something not just in Syria but also within ourselves.”

Hope eclipsed by despair

From their start in March 2011, nonviolent demonstrations met with merciless repression. That July, oppositionists and military defectors announced the formation of a “Free Syrian Army” to defend protesters and fight the regime. As this and other armed groups pushed the regime from large swaths of territory, new forms of grassroots organization and local governance emerged, indicating what society could accomplish if permitted the chance.

Still, as years passed, hope became eclipsed by despair.

The people I met described their despair witnessing the regime escalate bombardment, starvation sieges and other war crimes to reconquer areas from opposition control. Despair when Assad killed 1,400 people in a 2013 chemical attack, violating the United States’ purported “red line” but escaping accountability. Despair as hundreds of thousands of people disappeared into regime dungeons, condemned to a fate of torture worse than death. Despair as the number killed in Syria climbed by hundreds of thousands, and in 2014 the United Nations gave up counting more. Despair as over half the population was forced to flee their homes, and the word “Syria” became stuck, in minds around the world, to the words “refugee crisis.”

And then there was the despair as an entity called the Islamic State announced itself in 2013 and trampled on Syrians’ democratic aspirations in a newly horrific way.

“We don’t know where any of this is leading,” a rebel officer told me at that time. “All we know is that we’re everyone else’s killing field.”

Searching for home

With the help of external allies and the rest of the world’s inaction, Assad clawed back about 60% of the country by 2020 and penned the opposition in an enclave in the northwest.

Syria dropped from the headlines, even as regime bombing continued to kill civilians, economic meltdown plunged 90% of the population below the poverty line and the regime rotted into a narco state sustained by drug trafficking.

A woman I met during these years of stalemate summarized things bleakly: “The most important thing at this stage is to protect the last bit of hope that people have left.”

Meanwhile, millions of Syrian refugees, the lion’s share of them in the countries neighboring Syria, suffered poverty, legal precariousness and local populations who increasingly demanded their deportation.

The stories that I recorded gradually came to center on a different theme, which I made the focus of my second book: home.

For those compelled to flee, the word “home” connoted twin challenges: First, creating new lives where they might never have imagined stepping foot; and second, mourning old homes lost, destroyed or emptied of loved ones.

Many described the agony of reconciling their attachment to Syria with the sense that they were unlikely to see it again.

“You try as hard as you can to forget the homeland, but you can’t because it’s even more painful to be without any homeland at all,” a man lamented.

Finding home in refuge, in other words, was not only a matter of integration. It also meant finding a way to move forward when the hope for freedom in Syria, it seemed, could not.

This is why it is awe-inspiring to witness hope surge again. As I messaged Syrian friends and interlocutors this week, I was struck by how their jubilation echoed with stories that I used to record about 2011, but now on an even more astonishing scale.

Again and again, people said that their emotions were “indescribable” and “beyond words.” That they were simultaneously “laughing and crying.” That they “just couldn’t believe” that it – the it that they once did not dare voice out loud – finally happened.

Since Assad’s fall, many foreign governments and analysts have voiced foreboding warnings about the future. They need not; Syrians know better than anyone that the path ahead will not be easy.

For now, however, the role of those watching from afar is not to doubt, critique or speculate, but to honor this triumph of human hope.

Syrian playwright Saadallah Wannous famously said in 1996, “We are doomed by hope, and what happens today cannot be the end of history.” Those who refused to give up over the long years of violence, oppression and disappointment were right. Syrian history is just beginning.

Wendy Pearlman receives funding from Alexander von Humboldt Foundation Research Fellowship

Read These Next

AI’s growing appetite for power is putting Pennsylvania’s aging electricity grid to the test

As AI data centers are added to Pennsylvania’s existing infrastructure, they bring the promise of…

When civil rights protesters are killed, some deaths – generally those of white people – resonate mo

From the civil rights era of the 1960s until today, white victims of government violence have received…

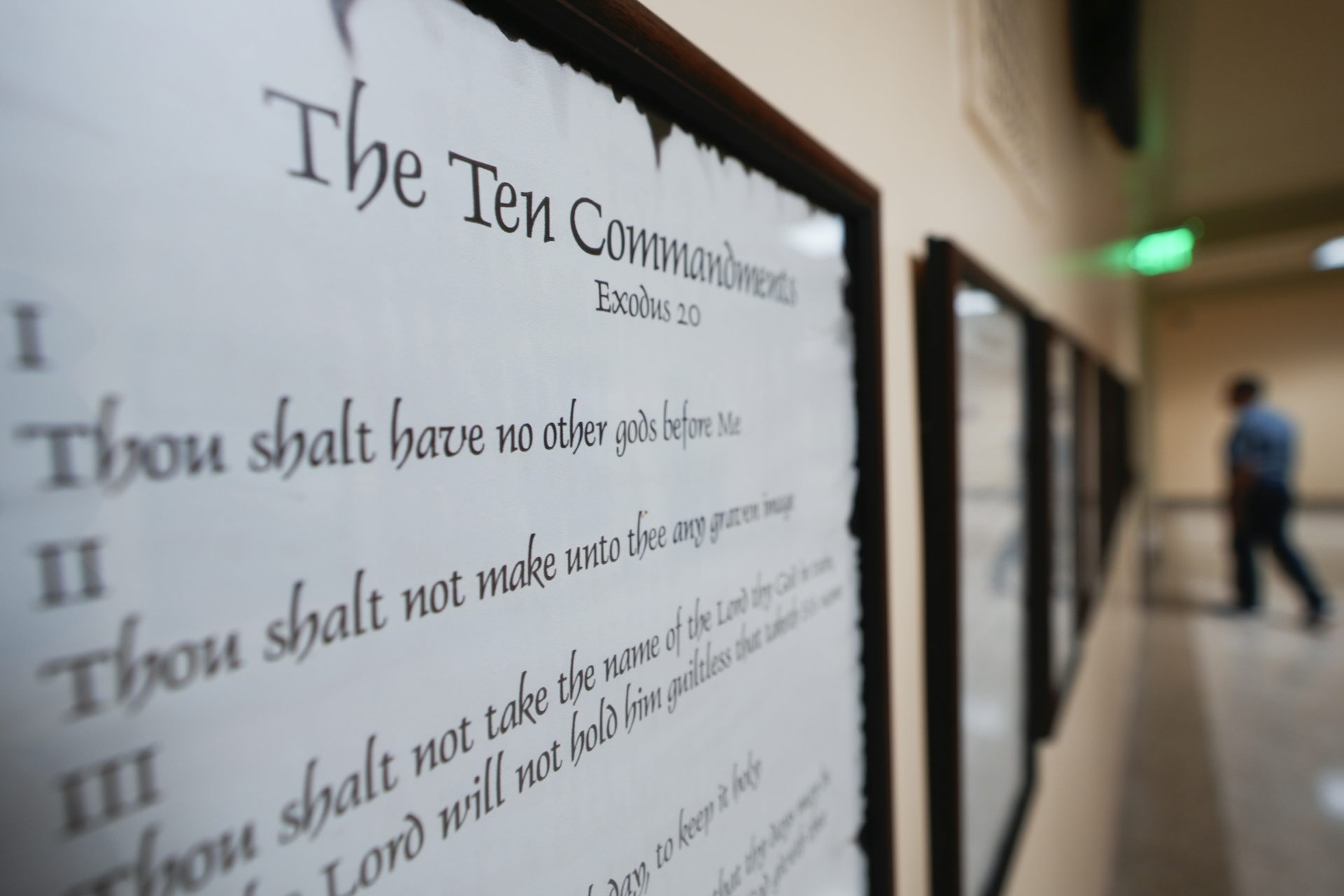

Baptists have helped shape debate about religious freedom for over 400 years – up to today’s 10 Comm

The phrase ‘separation of church and state’ dates back to a letter from Thomas Jefferson to a Baptist…