Why FEMA’s disaster relief gets political − especially when hurricane season and election season col

Disaster relief requires cooperative, healthy relationships between the president, federal agencies and state, local and tribal governments. But with politicians in the mix, trouble can happen.

Rumors and lies about government responses to natural disasters are not new. Politics, misinformation and blame-shifting have long surrounded government response efforts.

When Hurricane Harvey hit Houston in 2017, for example, rumors and misinformation both originated from and were spread by government, news and individual user accounts on social media. And after Hurricane Sandy in 2012, rumors about the storm were so widespread that even CNN’s live coverage of the event was inaccurate.

Those rumors don’t usually come from former presidents. Yet in the wake of hurricanes Helene and Milton, former President Donald Trump spread falsehoods about the federal government’s response to the disaster. Misinformation on the topic became so widespread that the Federal Emergency Management Agency, known as FEMA, set up a webpage to debunk the rumors spawned by Trump.

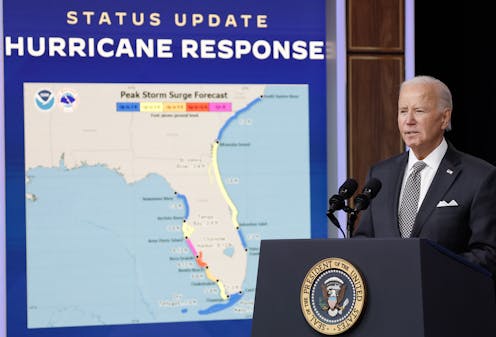

President Joe Biden responded angrily, calling the falsehoods that Trump and his followers spread “reckless, irresponsible” and “disturbing.” He also suggested Trump’s claims undermined the rescue and recovery work being done by local, state and federal authorities.

Disaster relief often becomes political because so many people are affected – and because there is a lot of media coverage surrounding hurricanes, floods and other major weather events. Additionally, relief requires a lot of money and coordination by high-profile elected officials.

The rhetoric around federal emergency management is made only more complicated because most people do not know that much about the federal law that governs disaster relief. Indeed, even state and local officials find navigating the details of the law and accompanying regulations difficult.

And finally, the law’s design and the timing of hurricane season can lead to politicization. Elected officials – politicians – are always involved in coordinating government response efforts, adding a layer of politics to disaster relief. The fact that hurricane and election seasons coincide only heightens the politics of such relief.

Explaining government responses to natural disasters

The Disaster Relief Act of 1974, as amended and now known as the Stafford Act, is the law that governs how the federal government responds to natural disasters and other emergencies.

But the act does not guarantee federal assistance to the communities affected by hurricanes or other natural disasters.

Instead, the governor of an affected state or the chief executive of an affected tribal government must ask the president for a disaster declaration. The request can be made before or after a storm hits but must show that the disaster is of such a severity and magnitude that the state, local or tribal governments cannot respond on their own.

Responding to such requests, Biden issued declarations covering eight states before and after Helene. He also issued a declaration for the Seminole Tribe and the state of Florida in response to Milton.

After the president issues a declaration, the federal government can begin to assist state, local and tribal governments. This includes coordinating all disaster relief assistance – from evacuations to recovery – provided by federal agencies, private organizations such as the Red Cross, and state and local governments.

Federal assistance can be financial or logistical. It covers everything from help repairing roads and restoring utility services to providing assistance and services, such as temporary housing, legal services and crisis counseling, to the people who have been affected by the disaster.

The number of federal agencies and employees involved in disaster relief is astounding. For example, thousands of federal personnel from FEMA, the Coast Guard, Army Corps of Engineers, Environmental Protection Agency and the departments of Defense, Energy, Health and Human Services, Housing and Urban Development, and Transportation are helping respond to Helene and Milton.

Several state and local officials also play key roles after a disaster declaration. Each state’s governor or tribe’s chief executive serves as the leading official for coordination of state and federal efforts. That person also designates an officer to serve as a liaison between the federal government and the state or tribe. And in each affected community, a local elected official leads the response on the ground. This is usually a city or town’s mayor.

Federalism in action

Implementation of the Stafford Act requires cooperative, healthy relationships between the president, federal agencies and state, local and tribal governments.

When done well, government disaster response is a prime example of what’s called “federalism” in action. Federalism involves the sharing of power between the national and state governments. The framers of the United States Constitution created this system of shared power so that the national government could solve coordination and capacity problems among the states, and the state governments could respond to the nuances of local circumstances.

In response to state government requests in the wake of Hurricane Helene, for example, Biden directed federal efforts to help those most affected. The federal government’s response has so far included working with over 450 state and local officials to ensure that those affected by the hurricane have everything from housing assistance to financial support for medical and funeral expenses.

Politics in the mix

The very things that the framers designed the federalist constitutional system to do, however, can create opportunities for political manipulation. The Stafford Act creates a system of emergency management that is highly decentralized and responsive to local needs.

But that decentralization also means that, because of their different perspectives, the officials involved in disaster response prioritize different things, which can lead to conflict.

For example, various officials involved in the response to Hurricane Helene have advocated for federal resources such as money and personnel to go toward restoring utilities, law enforcement, fire, health, communications and transportation services. How can the national government possibly choose between all of these necessary services?

Everything is made more complicated because, as studies have shown, on average, the officials in charge of making such decisions – elected officials and their appointees – have less experience in government than the career civil servants who work on a daily basis with the people affected by natural disasters.

As a result, the Stafford Act’s decision to place elected officials and their appointees in charge of emergency management could reduce the quality of government response.

Debating size and role of government

Elected officials’ different political leanings add another wrinkle. Debates over disaster response often reflect larger political debates such as those over the size and role of government.

The history of the Stafford Act provides an illustrative example. Traditionally, disaster relief was the responsibility of state and local government. But a series of natural disasters, including the Alaska earthquake in 1964 and hurricanes Betsy in 1965 and Camille in 1969, were so large in scale that the federal government had to step in and help.

In the aftermath of Camille, accusations of racial discrimination in the relief process and partisan squabbling over who was to blame for the ineffectiveness of the government’s response to the disaster mounted. Media and congressional attention on government mismanagement of the relief effort created a window for the expansion of the federal government’s role in the process and ultimately led to the passage of the first version of the Stafford Act.

Fast-forward 35 years and many of the same issues – racial discrimination, government mismanagement and politicization of relief – arose in 2005 in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. Media and congressional attention led to legislation that amended the Stafford Act and restructured FEMA and how the federal government responds to state and tribal requests for assistance.

Trump’s lies are from the same playbook – false claims about money being diverted to migrants and that relief efforts are being used only to help areas where Democrats live.

Yet the devastation left by Helene and Milton do raise questions about local and federal coordination in preparation for and response to natural disasters and has led to calls for Congress to pass reforms to improve equity, efficiency and effectiveness in government responses to natural disasters. Whether this reform is possible in such a contentious political climate remains an open question.

Jennifer L. Selin has received funding and/or support for her research on the executive branch from the Administrative Conference of the United States. The views in this piece are those of the author and do not represent the position of the Administrative Conference or the federal government.

Read These Next

Violent aftermath of Mexico’s ‘El Mencho’ killing follows pattern of other high-profile cartel hits

Members of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel have set up roadblocks and attacked property and security…

Crowdfunded generosity isn’t taxable – but IRS regulations haven’t kept up with the growth of mutual

Some Americans are discovering that monetary help they received from friends, neighbors or even strangers…

Algorithms that customize marketing to your phone could also influence your views on warfare

AI systems are getting good at optimizing persuasion in commerce. They are also quietly becoming tools…