African-American Music Appreciation Month: 5 essential reads

The story of African-American music is a story of eclipsing expectations and subverting norms.

To commemorate African-American Music Appreciation Month this June, California Senator Kamala Harris released a Spotify playlist with songs spanning genres and generations, from TLC’s “Waterfalls” to Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On.”

In a nod to the integral role African-American musicians play in the country’s rich musical legacy, we’ve decided to highlight our own “playlist” of articles, pieces that feature icons like Michael Jackson and Tupac Shakur, along with forgotten – but no less important – voices, from Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield to the Rev. T.T. Rose.

The first black pop star is born

Before Aretha Franklin, before Ella Fitzgerald, there was Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield. A self-taught opera singer born in 1820, Greenfield had to overcome the belief that blacks couldn’t actually sing.

Penn State music instructor Adam Gustafson tells the story of Greenfield’s rise, which made audiences reconcile their racism with their ears:

“Greenfield was met with laughter when she took to the stage. Several critics blamed the uncouth crowd in attendance; others wrote it off as lighthearted amusement. Despite the inauspicious beginning, critics agreed that her range and power were astonishing.”

Segregating sound

By the early 20th century, Americans were clamoring for the albums of black artists. The music industry was eager to oblige, but cordoned them off into a distinct genre: “race music.”

One of the most prominent early race labels was Paramount Records. Between 1917 and 1932, Paramount recorded a breathtaking range of seminal African-American artists. Unfortunately, as Penn State’s Jerry Zoltan explains, black artists like the Rev. T.T. Rose and the Pullman Porters Quartet were ruthlessly exploited – and eventually forgotten.

“Bottom line: if record companies could get away with it, there was no bottom line. No negotiated contract to sign. No publishing. No royalties. Anonymity was also implicit in the deal, so many black artists were forgotten, their only legacy the era’s brittle shellac disks that were able to withstand the wear of time.”

University of Maryland, Baltimore County’s Clifford Murphy describes how these same industry forces tried to pigeonhole an ex-con named Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter as a black blues artist.

But Lead Belly loved country stars like Gene Autry, and while he sang blues and spirituals, he also created songs influenced by the string band traditions of the white working class. Promoters, however, were interested in only a certain type of song:

“Though he had an immense repertoire, he was urged to record and perform songs like ‘Pick A Bale of Cotton,’ while songs considered ‘white,’ like ‘Silver Haired Daddy of Mine,’ were either downplayed or cast aside… Lead Belly was constrained by a commercial and cultural industry that wanted to present a certain archetype of African-American music.”

Michael Jackson breaks the mold

Only later would black artists be able to move freely across musical genres. Perhaps no artist stitched together a more diverse range of styles and influences than Michael Jackson, the King of Pop.

But Jackson was simultaneously derided as “Wacko Jacko,” a hopelessly deluded freak. McMaster University’s Susan Fast sees it differently. To Fast, the way Jackson lived his life was an extension of the risks he took in his music. Both were united by a central tenet: to collapse boundaries considered irrevocable.

“Michael Jackson – gender ambiguous; adored and reviled; human, werewolf, panther; black, white, brown; child, adolescent, adult – shattered the assumptions of a society that craves neat categories and compartmentalization. Order and normality are illusions, he said through his life and art.”

The triumph and tragedy of Tupac

In the 1980s, hip-hop – then a budding musical genre – found itself gravitating toward black nationalist messages. It was during this time that Tupac Shakur, the son of a Black Panther, came of age.

While R&B, soul and jazz musicians were largely silent about the challenges poor black communities faced, Tupac, in his music, directly confronted the hostile forces that threatened him and his peers: mass incarceration, poverty, illegal drugs and police brutality. But in Tupac’s meteoric rise and swift fall, UConn’s Jeffrey O.G. Ogbar sees the tragedies of an entire generation of black youth:

“Tupac’s life isn’t just an embodiment of the struggles, contradictions, creativity and promise of a generation. It also serves as a cautionary tale. His life’s abrupt end was a consequence of the allure of success, much like the pull of the streets.”

Read These Next

George Washington’s foreign policy was built on respect for other nations and patient consideration

For the nation’s first president, friendliness was strategy, not concession: the republic would treat…

Why the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette’s closure exposes a growing threat to democracy

When reputable local news outlets close, fewer people vote and get involved in local politics, and misinformation,…

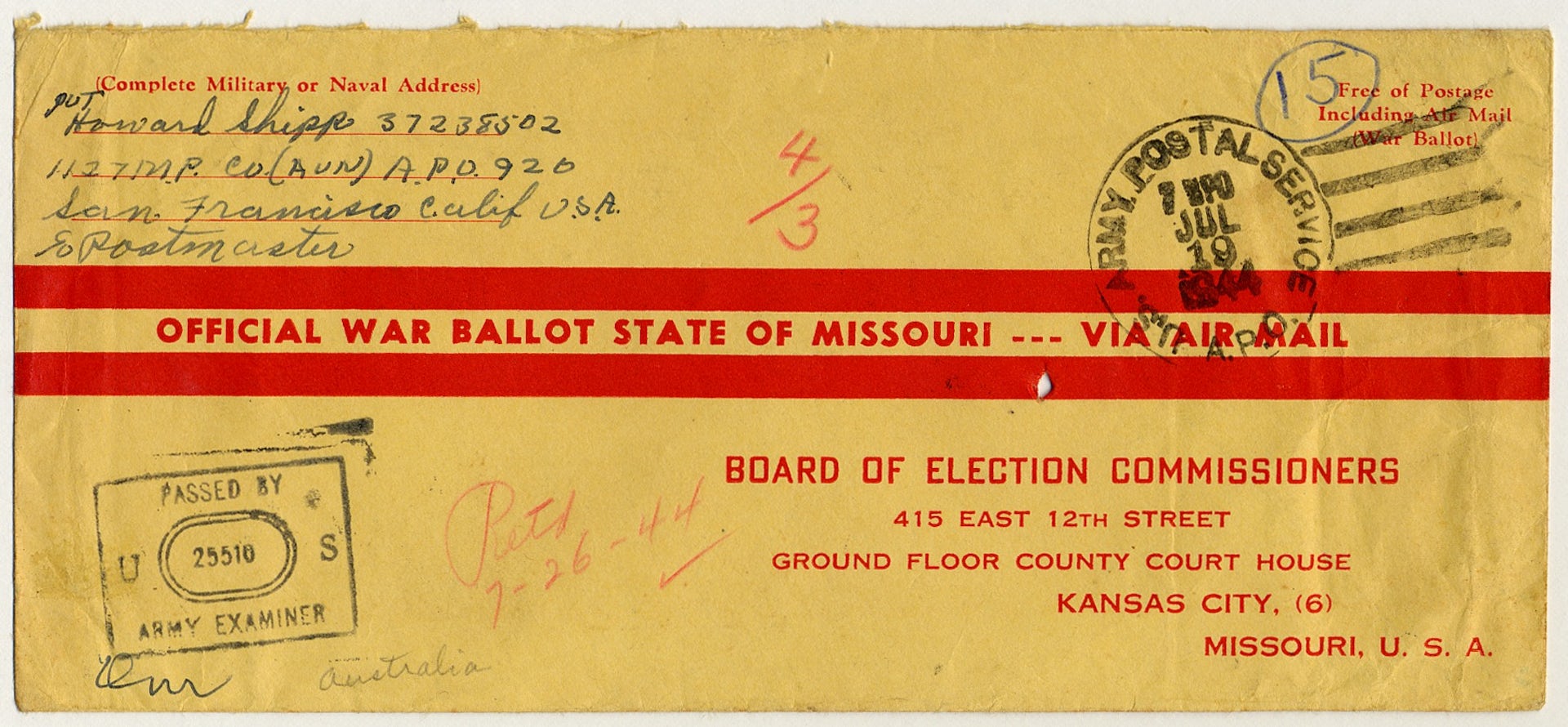

Americans have had their mail-in ballots counted after Election Day for generations − a Supreme Cour

29 states allow mail-in ballots postmarked by Election Day to be counted days after an election. A case…