The 17th-century cloth merchant who discovered the vast realm of tiny microbes – an appreciation of

Leeuwenhoek, who discovered bacteria, is one of the most important figures in the history of medicine, laying the groundwork for today's understanding of infectious disease.

Imagine trying to cope with a pandemic like COVID-19 in a world where microscopic life was unknown. Prior to the 17th century, people were limited by what they could see with their own two eyes. But then a Dutch cloth merchant changed everything.

His name was Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, and he lived from 1632 to 1723. Although untrained in science, Leeuwenhoek became the greatest lens-maker of his day, discovered microscopic life forms and is known today as the “father of microbiology.”

Visualizing ‘animalcules’ with a ‘small see-er’

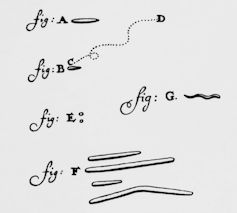

Leeuwenhoek didn’t set out to identify microbes. Instead, he was trying to assess the quality of thread. He developed a method for making lenses by heating thin filaments of glass to make tiny spheres. His lenses were of such high quality he saw things no one else could.

This enabled him to train his microscope – literally, “small see-er” – on a new and largely unexpected realm: objects, including organisms, far too small to be seen by the naked eye. He was the first to visualize red blood cells, blood flow in capillaries and sperm.

Leeuwenhoek was also the first human being to see a bacterium – and the importance of this discovery for microbiology and medicine can hardly be overstated. Yet he was reluctant to publish his findings, due to his lack of formal education. Eventually, friends prevailed upon him to do so.

He wrote, “Whenever I found out anything remarkable, I thought it my duty to put down my discovery on paper, so that all ingenious people might be informed thereof.” He was guided by his curiosity and joy in discovery, asserting “I’ve taken no notice of those who have said why take so much trouble and what good is it?”

When he reported visualizing “animalcules” (tiny animals) swimming in a drop of pond water, members of the scientific community questioned his reliability. After his findings were corroborated by reliable religious and scientific authorities, they were published, and in 1680 he was invited to join the Royal Society in London, then the world’s premier scientific body.

Leeuwenhoek was not the world’s only microscopist. In England, his contemporary Robert Hooke coined the term “cell” to describe the basic unit of life and published his “Micrographia,” featuring incredibly detailed images of insects and the like, which became the first scientific best-seller. Hooke, however, did not identify bacteria.

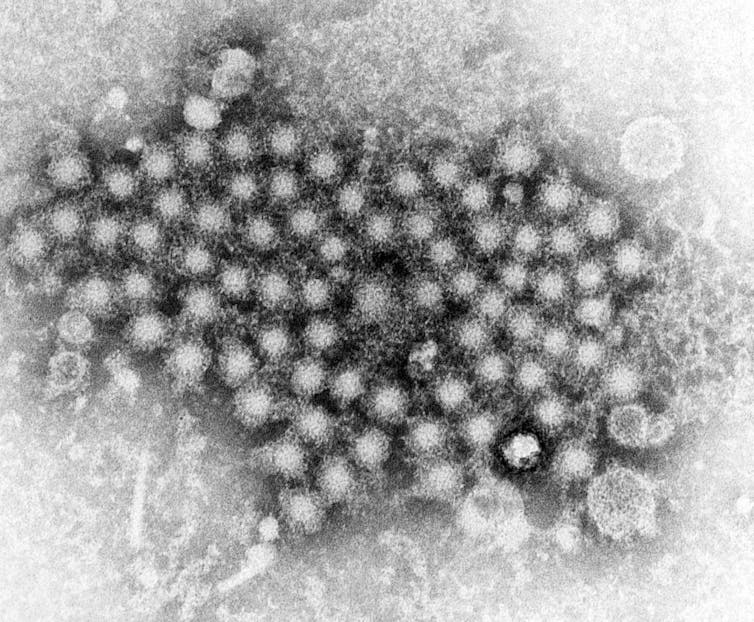

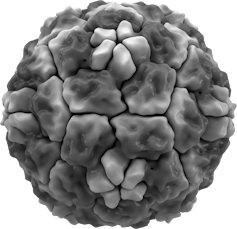

Despite Leuwenhoek’s prowess as a lens-maker, even he could not see viruses. They are about 1/100th the size of bacteria, much too small to be visualized by light microscopes, which because of the physics of light can magnify only thousands of times. Viruses weren’t visualized until 1931 with the invention of electron microscopes, which could magnify by the millions.

A vast, previously unseen world

Leeuwenhoek and his successors opened up, by far, the largest realm of life. For example, all the bacteria on Earth outweigh humans by more than 1,100 times and outnumber us by an unimaginable margin. There is fossil evidence that bacteria were among the first life forms on Earth, dating back over 3 billion years, and today it is thought the planet houses about 5 nonillion (1 followed by 30 zeroes) bacteria.

Some species of bacteria cause diseases, such as cholera, syphilis and strep throat; while others, known as extremophiles, can survive at temperatures beyond the boiling and freezing points of water, from the upper reaches of the atmosphere to the deepest points of the oceans. Also, the number of harmless bacterial cells on and in our bodies likely outnumber the human ones.

Viruses, which include the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 that causes COVID-19, outnumber bacteria by a factor of 100, meaning there are more of them on Earth than stars in the universe. They, too, are found everywhere, from the upper atmosphere to the ocean depths.

Strangely, viruses probably do not qualify as living organisms. They can replicate only by infecting other organisms’ cells, where they hijack cellular systems to make copies of themselves, sometimes causing the death of the infected cell.

It is important to remember that microbes such as bacteria and viruses do far more than cause disease, and many are vital to life. For example, bacteria synthesize vitamin B12, without which most living organisms would not be able to make DNA.

Likewise, viruses cause diseases such as the common cold, influenza and COVID-19, but they also play a vital role in transferring genes between species, which helps to increase genetic diversity and propel evolution. Today researchers use viruses to treat diseases such as cancer.

Scientists’ understanding of microbes has progressed a long way since Leeuwenhoek, including the development of antibiotics against bacteria and vaccines against viruses including SARS-CoV-2.

But it was Leeuwenhoek who first opened people’s eyes to life’s vast microscopic realm, a discovery that continues to transform the world.

[Understand new developments in science, health and technology, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s science newsletter.]

Richard Gunderman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

As DOJ begins to release Epstein files, his many victims deserve more attention than the powerful me

Powerful men connected to Jeffrey Epstein are named, dissected and speculated about. The survivors,…

Medieval peasants probably enjoyed their holiday festivities more than you do

The Middle Ages weren’t as dreary and desperate as you’d think, and peasants often had weeks of…

Why are some Black conservatives drawn to Nick Fuentes?

Black Americans and white nationalists have joined forces in the past. And a number of cultural and…