Why blackface?

The public was shocked by the blackface image on Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam's yearbook page. But if blackface is now taboo, there was a time when it played a big role in American culture.

Blackface is part of American culture’s DNA.

But America has forgotten that.

For almost two weeks, conflict has raged over the use of blackface by two current Virginia politicians when they were younger. The revelations have threatened the men’s jobs and their standing in the community.

The use of blackface is now politically and culturally radioactive. Yet there was a time when it wasn’t.

I teach the history of blackface in the United States. Like much of America, my undergraduate students suffer from a kind of historical amnesia about its role in American culture. They know little about its long history, and they haven’t considered its prevalence and significance in everyday American life.

Most of all, they’ve never asked themselves, “Why blackface?”

Cultural persistence

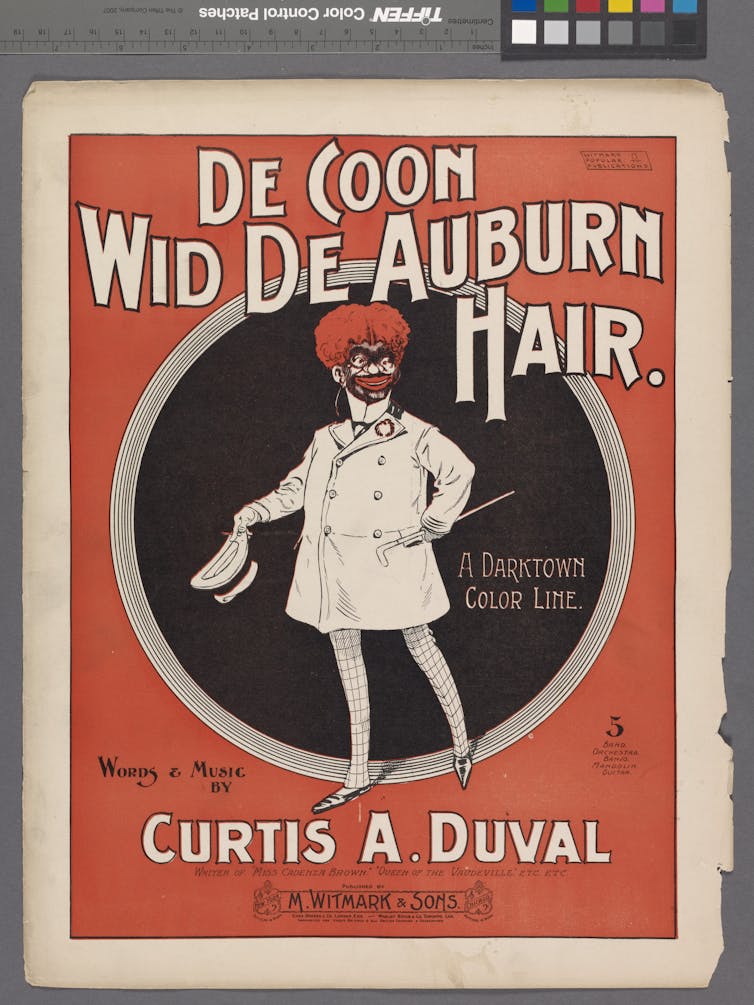

The blackface minstrel show was a form of burlesque theater that emerged in the 19th-century U.S. in which white men painted their faces black in order to mock people of African descent.

It held sway as one of the most popular forms of entertainment in the 19th century. In the early 20th century, Hollywood studios used the popularity of blackface to draw a mass audience to the new medium of film.

After World War II, even as the civil rights movement emerged, blackface remained a staple of cartoons, community theater, toys, household decorations and corporate branding.

American music — from the Great American Songbook of 1930s and ‘40s to rock ‘n’ roll in the 1950s and ‘60s — finds its roots in the minstrel shows of the 19th century.

With the recent blackface scandals in Virginia, we’ve also come to reckon with blackface’s importance to what it meant to be a young white man in the South in the 1980s.

Prejudice and profit

Blackface has always been flat-out racist.

Since its emergence in the 1830s in the taverns and on the theater stages of New York and other northern cities – it originated in the North, not the slave South – blackface has involved the vicious ridiculing of people of African descent.

White men blacked up by smearing burnt cork on their faces. They exaggerated their red lips and wore outlandish costumes, portraying character types like the raggedly slave, dubbed Jim Crow, or the ostentatious but simpleminded dandy, Zip Coon.

Minstrel shows consisted of jokes and clowning skits. The blackface characters mispronounced words and acted like bumpkins. They sang songs, sometimes sentimental and sometimes randy. In the minstrel show, white men from behind the black mask forged some of America’s most racist stereotypes.

And, it’s worth emphasizing, they made a good living at it. Blackface turned prejudice into profit.

Perhaps blackface’s profitable prejudice answers the question about why America so often returned to it in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Blackface offered the perfect entertainment for a slave nation and then, after the Civil War, a society built on racial segregation.

Cauldron of contradictions

But a number of scholars over the last few decades have proposed that there’s a great deal more to blackface than racist caricature.

For instance, historians have examined the ways immigrants put on the black mask as part of a process of becoming American.

Irish immigrants in the 1830s and 1840s and then Jewish immigrants in the early 20th century dominated blackface performance. In part it allowed them entry into the entertainment industry and American popular consciousness. In “The Jazz Singer” (1927), Al Jolson’s character, the son of a Jewish cantor, blacks up to become a star.

But new immigrants also attempted to established their social position in American society by distinguishing themselves from the lowest rung on the social latter through a blackface burlesquing of African-Americans.

Ralph Ellison, the author of the mid-century novel of African-American experience, “Invisible Man,” wrote brilliantly about blackface.

Ellison saw America as a cauldron of contradictions. It preached equality but practiced slavery and discrimination. It valued liberty and the recognition of all people’s humanity, while treating many of its citizens like things and animals.

For Ellison, blackface was America’s way of living with such contradictions. In a 1958 essay, Ellison asserted that blackface “constituted a ritual of exorcism.” In blackface, the black figure represented the negative aspects of American society - slavery, inequality, immorality, exploitation. These negative aspects were exorcised and disavowed by turning them into a big joke in the blackface show.

This “exorcism” meant that white Americans could consider themselves and their nation as good and decent while still engaging in racist behavior.

Ellison presented blackface not as outside of America’s core values, but as telling “us something of the operations of American values,” as he put it.

Yearning for blackface

Like Ellison, many of the recent historians of blackface suggest more is at stake than racial animus. The cultural historian Eric Lott goes a step further and argues that blackface is infused with something like love.

In his influential book “Love and Theft,” Lott sees the donning of the mask as a fetishistic fascination with blackness.

Blackface fascinates white men because it allows them sexual license and access to a purportedly virile, disobedient, yet authentic form of masculinity that rebels against middle-class American life, Lott argues.

But inhabiting blackness, Lott explains, produces great anxiety in those who take up the black mask. The masked men distance themselves from blackness – it’s all a joke in good fun – almost as quickly as they inhabit it because blackness, while deeply desired, is also dangerous to their white privilege.

Lott sees this dynamic as exploitation – the “theft” of his title – but it’s exploitation built on fascination and desire.

Lott’s history focuses on working-class men during the decades before the Civil War, but it’s not a big step from the “love and theft” of antebellum blackface to Mick Jagger cakewalking across the stage like Zip Coon or suburban white kids spittin’ rhymes.

‘Masking jokers’

I suspect something like this “love and theft” dynamic was happening in 1980s Virginia.

In addition to the blackface image on Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam’s medical school yearbook page from 1983, we also find him in two additional photos.

In one he poses next to a muscle car, and in the other he is pictured in a rancher’s 10-gallon hat. In these two images, Northam tries to present a masculine virility. Was that sense of virility quickly slipping away for the soon-to-be pediatrician and future politician?

These are images, too, of a South that was likewise quickly disappearing in the 1980s. This South was as much a New South of suburbs, international corporations and newly established immigrant communities as it was the old Dixie of 10-gallon-hat ranchers and of moonshiners who used souped-up stock cars to deliver their goods.

Blackface in the 1980s was perhaps a way for white Southerners to get back some of the old Southern spunk, its sense of virility and masculinity. The KKK figure, standing shoulder-to-shoulder with the blackface figure on Northam’s yearbook page, is present to make sure that all know that everyone is really buddies here and this is a joke – which of course it is and it isn’t.

“Change the Joke and Slip the Yoke” is the title of Ralph Ellison’s brilliant essay on blackface from 1958.

But the joke of blackface is still very much with us. We haven’t slipped its yoke.

“America,” Ellison wrote, “is a land of masking jokers.”

Michael Millner ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son poste universitaire.

Read These Next

Bradley Cooper, Cillian Murphy and the myths of Method acting

Hopefully, Academy Award winners will be chosen because voters believed in the actors’ performances…

Ben Shapiro’s hip-hop hypocrisy and white male grievance lands him on top of pop music charts for a

Since its birth 50 years ago, hip-hop music has embraced artists of every race and ethnic background.…

The creepy clown originated in the crass and bawdy circus clowns of the 19th century

Today’s creepy clowns are not a divergence from tradition, but a return to it.