Judging the judges: Scandals have the potential to affect the legitimacy of judges – and possibly th

Courts have no army or police force to enforce their decisions. Their power rests on their legitimacy in the public eye. How does scandal affect that?

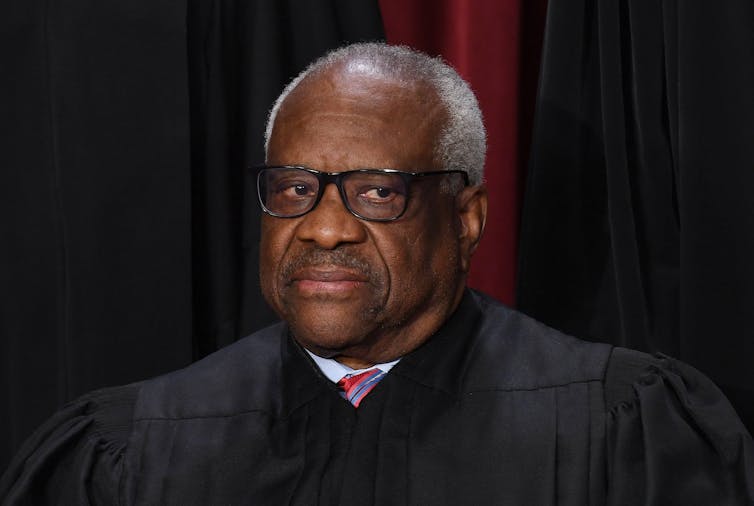

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas is no stranger to controversy.

In 1991, during his confirmation hearings in the Senate, Thomas faced accusations of sexual harassment from a former colleague and law school professor, Anita Hill.

More recently, Thomas’ personal relationship with a real estate billionaire, Republican donor Harlan Crow, has come under scrutiny. Crow paid for lavish vacations for Thomas and his wife. Thomas and Crow had undisclosed real estate deals. Crow also made tuition payments for Thomas’ grandnephew.

Nearly all of these gifts and financial dealings were absent from Thomas’ required financial disclosure forms. While there is uncertainty on the specific reporting requirements for the vacations and real estate deals, it seems likely that the tuition payments received on behalf of Thomas’ family would be subject to disclosure requirements as financial gifts.

These recent discoveries have prompted backlash, ranging from calls for ethics reform to demands for impeachment.

But scandal and controversy are not new to the federal courts. As political science professors, we study how scandals and other phenomena affect public support for the Supreme Court. Prior research finds that when citizens perceive the courts as legitimate, citizens are less willing to challenge judicial decisions – even those that individuals disagree with.

Ultimately, scandal has a strong potential to undermine public perceptions. And as legitimacy diminishes, judges are likely to face increased public scrutiny for their policy decisions.

Judicial scandals different from political scandals

Beyond Thomas, other Supreme Court justices and their close family members have recently faced allegations of wrongdoing.

These range from Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s alleged sexual assault to a controversial real estate sale involving Justice Neil Gorsuch.

Recent history is replete with instances of judicial nominees and federal judges immersed in scandal and controversy – from taking bribes to tax fraud, from using illicit drugs with an exotic dancer to making court clerks watch obscene material.

These behaviors would be a problem in any government institution. Yet, unlike democratically elected officials, all U.S. Supreme Court justices and judges on the lower federal courts are unelected and insulated from direct electoral repercussions. Presidents nominate Supreme Court justices and federal court judges when a vacancy emerges. Once confirmed by a majority in the Senate, these individuals cannot be removed from the bench unless they are impeached by the House of Representatives and removed by a two-thirds majority vote in the Senate.

Such institutional dynamics provide broad protections for federal judges, including those embroiled in scandal and controversy. Beyond the threat of impeachment and removal, no other recourse is available to sanction judges for improprieties or ethical controversies.

In fact, Congress has moved to impeach lower court federal judges in only the most extreme circumstances. To date, no Supreme Court justice has been impeached and removed from office, although Samuel Chase was impeached in 1801 but ultimately acquitted in the Senate.

Public opinion and federal court legitimacy

Given this reality, scholars, pollsters and commentators focus their attention on how the public may punish judges and the courts through another means: judgments of their legitimacy.

Since the courts are unable to enforce their rulings – they do not have a police force or a military at their disposal – they must rely on public support to ensure broad compliance and implementation of their decisions.

When citizens perceive that federal courts exercise power legitimately, they are unlikely to challenge decisions they disagree with or the judges who made them. The Supreme Court historically has a deep reservoir of goodwill among the public. Scholarly evidence suggests that the Supreme Court uniquely benefits from what’s called a positivity bias, which means that people tend to perceive it more positively compared to Congress and the president.

Yet the federal judiciary faces threats to its legitimacy across all levels, from the Supreme Court to district courts. These include political polarization, which can lead the public to see courts as blatantly partisan institutions. Political science research demonstrates that support for the Supreme Court varies depending on the partisan viewpoint of survey respondents. Studies also suggest that the public views the Supreme Court less favorably when the court is perceived as politically distant from one’s own partisan preferences. Researchers also find that perceptions that the court favors liberal policies result in lower job approval ratings.

What researchers have less insight on is whether the public alters its support for the judiciary in light of scandal. The potentially corrosive implications of scandal have been thrust into the limelight with the recent revelations of impropriety concerning several Supreme Court justices.

Punishment for scandals

Scandal holds the potential to shake the confidence and trust the American public has in its judicial institutions. Our research, which predates the recent media reports on Thomas, looks at whether scandals meaningfully diminish citizen support for members of the judiciary, and the court as an institution.

Relying on multiple survey experiments, we examined the effect of varying scandals – ethical, financial and sexual – among hypothetical Supreme Court nominees and hypothetical sitting lower court judges.

In both cases and across scandal types, we found that the public punishes individual nominees and judges through diminished support. That is, respondents provided lower levels of job approval for a hypothetical judge who faced accusations of scandal compared to a judge who faced no such accusation. Notably, however, scandals did not harm the public’s perceptions of the federal courts’ legitimacy.

In other words, we found no effect of hypothetical scandal on respondents’ beliefs that courts are generally fair and should retain the right to make controversial decisions, even when a majority disagrees. This suggests that while the public holds judges associated with scandal in low regard, the negative effects of individual scandals do not permeate the institution of the courts.

We cannot say whether the harmful effects of scandal persist over time. Perhaps, negative impressions of individuals immersed in scandal will dissipate. Additional research is needed to examine whether a spate of scandals – involving multiple judges, with greater degrees of perceived severity – would result in a critical mass that undermines the foundations of public support for the courts as esteemed institutions.

Yet so far, our findings suggest that the latest round of scandals and controversies surrounding justices’ personal behavior will have minimal effect on eroding public support for federal courts.

Ali S. Masood receives funding from the National Science Foundation.

Joshua Boston received funding for this research from the Bowling Green State University Office of Sponsored Programs and Research and Department of Political Science.

Benjamin J. Kassow and David Miller do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Trump’s immunity arguments at Supreme Court highlight dangers − while prosecutors stress larger dang

The case argued before the Supreme Court has profound implications for Donald Trump − but also for…

How bird flu virus fragments get into milk sold in stores, and what the spread of H5N1 in cows means

Five livestock experts who study infectious diseases in the dairy industry explain the risks.

Large retailers don’t have smokestacks, but they generate a lot of pollution − and states are starti

For decades, big-box retailers have evaded federal regulation of the pollution their operations generate.…