The belief that demons have sex with humans runs deep in Christian and Jewish traditions

Stella Immanuel, who made headlines recently regarding a false coronavirus cure claim, has many beliefs related to how demons are a threat to humans. An expert explains their long religious history.

Houston physician and pastor Stella Immanuel – described as “spectacular” by Donald Trump for her promotion of unsubstantiated claims about anti-malaria drug hydroxychloroquine as a “cure” for COVID-19 – has some other, very unconventional views.

As well as believing that scientists are working on a vaccine to make people less religious and that the U.S. government is run by reptilian creatures, Immanuel, the leader of a Christian ministry called Fire Power Ministries, also believes sex with demons causes miscarriages, impotence, cysts and endometriosis, among other maladies.

It has opened her up to much ridicule. But, as a scholar of early Christianity, I am aware that the belief that demons – or fallen angels – regularly have sex with humans runs deep in the Jewish and Christian traditions.

Demon sex

The earliest account of demon sex in Jewish and Christian traditions comes from the Book of Genesis, which details the origins of the world and the early history of humanity. Genesis says that, prior to the flood of Noah, fallen angels mated with women to produce a race of giants.

The brief mention of angels breeding with human women contains few details. It was left to later writers to fill in the gaps.

In the third century B.C., the “Book of the Watchers,” an apocalyptic vision written in the name of a mysterious character named Enoch mentioned in Genesis, expanded on this intriguing tale. In this version, the angels, or the “Watchers,” not only have sex with women and birth giants, but also teach humans magic, the arts of luxury and knowledge of astrology. This knowledge is commonly associated in the ancient world with the advancement of human civilization.

The “Book of the Watchers” suggests that fallen angels are the source of human civilization. As scholar Annette Yoshiko Reed has shown, the “Book of the Watchers” had a long life within Jewish and early Christian communities until the middle ages. Its descriptions of fallen angels were widely influential.

The story is quoted in the canonical epistle of Jude. Jude cites the “Book of the Watchers” in an attack on perceived opponents who he associates with demonic knowledge.

Christians in the second century A.D., such as the influential theologian Tertullian of Carthage, treated the text as scripture, though it is only considered scripture now by some Orthodox Christian communities.

Tertullian retells the story of the Watchers and their demonic arts as a way to discourage female Christians from wearing jewelry, makeup, or expensive clothes. Dressing in anything other than simple clothes, for Tertullian, means that one is under the influence of demons.

Christians like Tertullian came to see demons behind almost all aspects of ancient culture and religion.

Many Christians justified abstaining from the everyday aspects of ancient Roman life, from consuming meat to wearing makeup and jewelry, by arguing that such practices were demonic.

Christian fascination with demons having sex with humans developed significantly in the medieval world. Historian Eleanor Janega, has recently shown that it was in the medieval period that beliefs about nocturnal demon sex – those echoed by Immanuel today – became common.

For example, the legendary magician Merlin, from the tales of King Arthur, was said to have been sired by an incubus, a male demon.

Demonic deliverance

For as long as Christians have worried about demons, they have also thought about how to protect themselves from them.

The first biography of Jesus, the Gospel of Mark, written around A.D. 70, presents Jesus as a charismatic preacher who both heals people and casts out demons. In one of the first scenes of the gospel, Jesus casts an unclean spirit out of a man in the synagogue at Capernaum.

In one of his letters to the Corinthians, the apostle Paul argued that women could protect themselves from being raped by demons by wearing veils over their heads.

Christians also turned to ancient traditions of magic and magical objects, such as amulets, to help ward off spiritual dangers.

Evangelicalism and Pentecostalism

In the wake of the Enlightenment, European Christians became deeply embroiled in debates about miracles, including those related to the existence and casting out of demons.

For many, the emergence of modern science called such beliefs into question. In the late 19th century, Christians who sought to retain belief in demons and miracles found refuge in two separate but interconnected developments.

A large swath of American evangelicals turned to a new theory called “dispensationalism” to help them understand how to read the Bible. Dispensationalist theologians argued that the Bible was a book coded by God with a blueprint for human history, past, present and future.

In this theory, human history was divided into different periods of time, “dispensations,” in which God acted in particular ways. Miracles were assigned to earlier dispensations and would only return as signs of the end of the world.

For dispensationalists, the Bible prophesied that end of the world was near. They argued that end would occur through the work of demonic forces operating through human institutions. As a result, dispensationalists are often quite distrustful and prone to conspiratorial thinking. For example, many believe that the United Nations is part of a plot to create a one world government ruled by the coming Antichrist.

Such distrust helps explain why Christians like Immanuel might believe that reptilian creatures work in the U.S. government or that doctors are working to create a vaccine that makes people less religious.

Meanwhile the end of the 19th century also saw the emergence of the Pentecostal movement, the fastest growing segment of global Christianity. Pentecostalism featured a renewed interest in the work of the Holy Spirit and its manifestation in new signs and wonders, from miraculous healings to ecstatic speech.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]

As scholar André Gagné has written, Immanuel has deep ties to a prominent Pentecostal network in Nigeria – Mountain of Fire Ministries or MFM founded in 1989 in Lagos by Daniel Kolawole Olukoya, a geneticist turned popular preacher. Olukoya’s church has developed into a transnational network, with offshoots in the U.S. and Europe.

Like many Pentecostals in the Global South, the Mountain of Fire Ministries believe spiritual forces can be the cause of many different afflictions, including divorce and poverty.

Deliverance Christianity

For Christians like Immanuel, spirits pose a threat to humans, both spiritually and physically.

In her recent book “Saving Sex,” religion scholar Amy DeRogatis shows how beliefs about “spiritual warfare” grew increasingly common among Christians in the middle of the last century.

These Christians claimed to have the knowledge and skills required to “deliver” humans from the bonds of demonic possession, which can include demons lodged in the DNA. For these Christians, spiritual warfare was a battle against a dangerous set of demonic foes that attacked the body as much as the soul.

Belief that demons have sex with humans is, then, not an aberration in the history of Christianity.

It might be tempting to see Immanuel’s support for conspiracy theories as separate from her claims that demons cause gynecological ailments.

However, because demons have also been associated with influencing culture and politics, it is not surprising that those who believe in them might distrust the government, schools and other things nonbelievers might take to be common sense.

Cavan W. Concannon ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son poste universitaire.

Read These Next

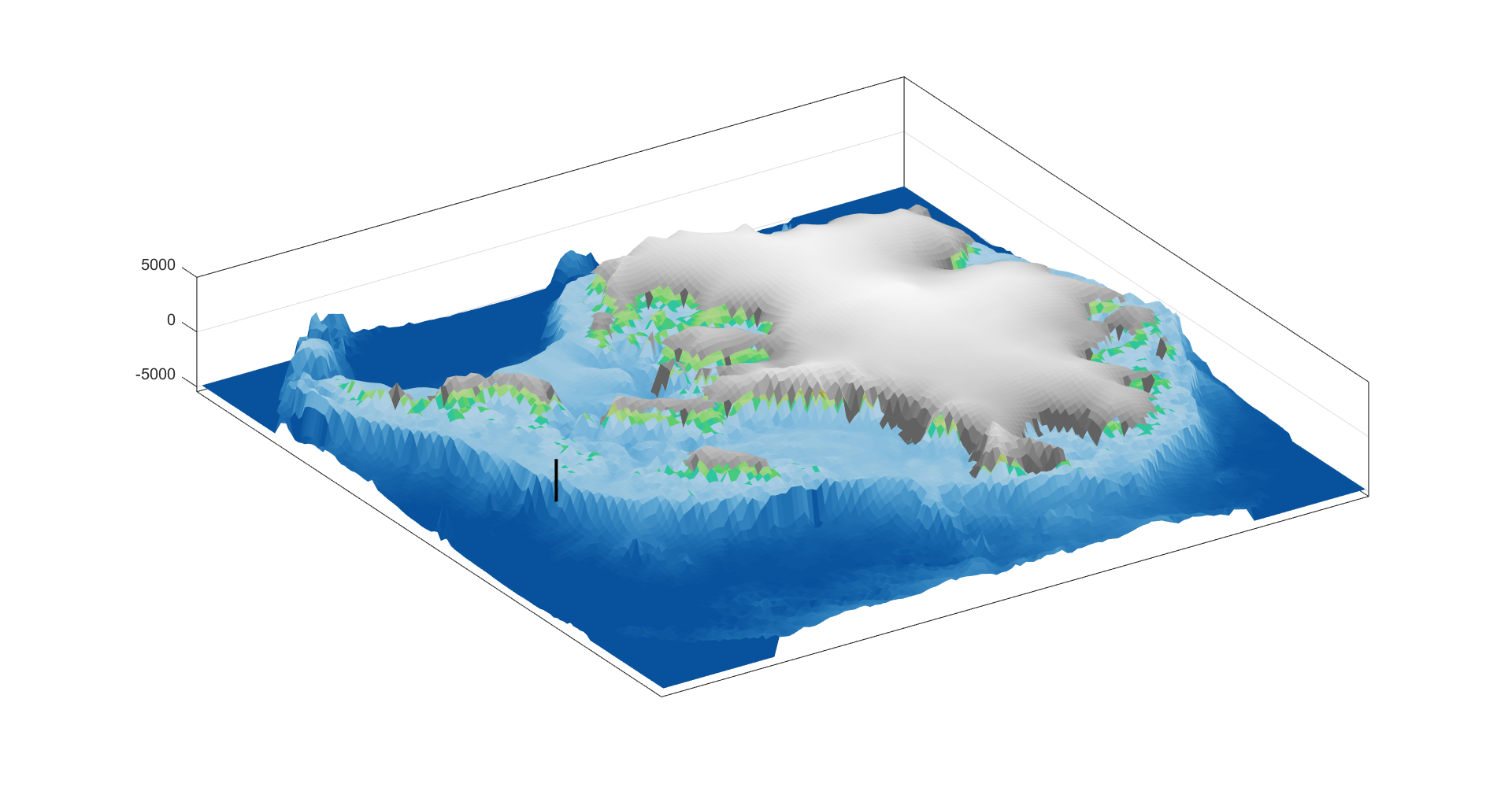

West Antarctica’s history of rapid melting foretells sudden shifts in continent’s ‘catastrophic’ geo

A picture of what West Antarctica looked like when its ice sheet melted in the past can offer insight…

The celibate, dancing Shakers were once seen as a threat to society – 250 years later, they’re part

‘The Testament of Ann Lee,’ Mona Fastvold’s 2025 film, depicts part of the long history of Shaker…

From truce in the trenches to cocktails at the consulate: How Christmas diplomacy seeks to exploit s

World leaders like to talk up peace at Christmastime. But alongside the tales of seasonal breaks in…