How state power regulators are making utilities account for the costs of climate change

States are folding the social and economic costs of burning fossil fuels into their electricity policies, giving utilities a financial incentive to reduce greenhouse emissions.

The electricity powering your computer or smartphone that makes it possible for you to read this article could come from one of several sources. It’s probably generated by burning natural gas or coal or from operating a nuclear reactor, unless it’s derived from hydropower or wind or solar energy. Who gets to choose?

In many states, it’s up to the utilities, the companies that bill you for electricity. Costs often weigh heavily in their decisions. But deciding which costs to consider is a very subjective process.

If your utility accounts for the toll taken by climate change, like Xcel Energy in Colorado does, your state electricity regulator probably makes the company do that. This approach is one behind-the-scenes way that a growing number of states are addressing global warming.

As scholars who study the intersection between policies that deal with climate change and energy, we have studied the rules that govern electric utilities across the nation. Our new report sheds light on where state regulators have the ability to make rules that mandate action on climate change.

States, electricity and climate change

Every additional ton of the greenhouse gas emissions from burning fossil fuels to generate electricity contributes to climate change. This carbon pollution has many negative consequences, both to the physical world and also to global social and economic systems.

But utilities don’t always tally the costs of these consequences. Because dealing with climate change is astronomically expensive, we believe that this should change.

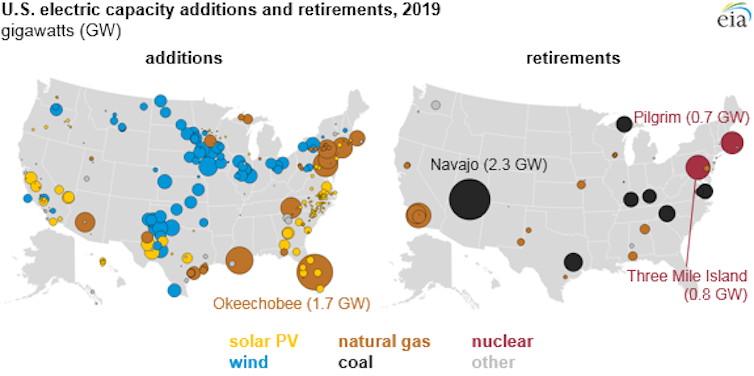

Utilities still largely rely on coal, natural gas and nuclear energy to keep the lights on. These companies rely on older technologies in part because those facilities are already built and, to a degree, because of how much it costs to start up and shut down power plants. What’s more, fossil fuels have generally been cheaper than other energy sources until somewhat recently.

But when state regulators require utilities to factor in the effects from burning fossil fuels, a big investment to get a large-scale wind or solar operation up and running becomes a better bargain. And since making electricity from cleaner energy sources has been steadily getting cheaper, factoring in climate costs could help speed up the process of phasing out climate-altering fossil fuels.

Different ways to do it

Some utilities are voluntarily including a line item in their balance sheets that estimates what their impact on the climate will be in monetary terms. Others are going this route due to the growing number of state electricity regulators that make it mandatory. We have determined that 10 states now account for climate costs in some way by regulating power companies.

Other states are starting to make bold proposals to reduce their emissions too.

A number of newly elected governors are making climate change a centerpiece of state policy in places where it had been an afterthought.

Some of these proposals focus on limiting carbon pollution to a certain level, others on increasing the generation of wind, solar and hydroelectric power, and others on making buildings and appliances more energy-efficient. All of these policies can be effective in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. But there are plenty of states in which a command-and-control policy where a regulator basically makes industries do a certain thing – like banning climate-warming chemicals used in refrigerators and air conditioners – might be unpopular.

There are also market-based options, where regulators encourage companies to do certain things without outright requiring them. In the U.S., this is mainly through the carbon-trading programs underway in places like California and the East Coast states that belong to the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative.

Americans in general support a shift toward more renewable energy, and energy regulation increasingly reflects that sentiment. Even in many of the so-called “purple states” like Nevada and Colorado, where leadership is divided between Democrats and Republicans, utility companies must tell the public how much their fossil-fuel pollution will cost because electricity regulators require it.

Who makes the rules?

Electric utilities, like ConEd if you live in New York, or PacifiCorp if you’re in California, Washington State, Utah, and other western states, have to follow a set of rules. These rules are created on a state-by-state basis by regulators, who are usually members of public utilities commissions. And because individual states are making these policy decisions, what each state chooses to do matters.

These regulators get their marching orders in multiple ways. State legislatures may pass laws that must be carried out by the commissions. Governors may ask them to make policy directly, through executive orders. Sometimes regulators end up making decisions in one proceeding that then change the rules across the board.

This avenue really depends on what the commissions are allowed to do in the first place, which is either set out in a law or set of laws – many states have whole sections of public utilities codes – or in the state constitution. Some regulators have a lot of freedom and autonomy, others not so much. In some cases, public utilities commissions are coming up with policies that reduce carbon pollution without any other statewide climate plan.

New approaches

A growing number of states have established policies that make power companies account for the costs of climate effects caused by pollution they create. The list spans the nation, from New York to California and Washington state, plus many places in between.

In Colorado and Nevada, utilities must estimate how much carbon pollution their electricity generation produces, and include this information in the plans they submit to state regulators. The Minnesota Public Utilities Commission does something similar. Other examples of states accounting for climate change behind the scenes, can be found on our Cost of Carbon Project website.

In these states, regulators have ordered utilities to estimate the harm caused by their greenhouse gas emissions when deciding between which sources to use.

The electricity business is changing rapidly. We get that state regulators might not matter so much once market forces make solar and wind not just a better deal than coal but also more affordable than natural gas.

In the meantime, while the economy transitions to the point where it no longer generates greenhouse gas pollution, we believe that state utility regulators can make a big difference.

Iliana Paul's employer, Institute for Policy Integrity at NYU School of Law, receives funding from the Energy Foundation and the Heising-Simons Foundation for work including research on state climate and energy policy.

Denise Grab's employer, Institute for Policy Integrity at NYU School of Law, receives funding from the Energy Foundation and the Heising-Simons Foundation for work including research on state climate and energy policy.

Read These Next

TikTok fears point to larger problem: Poor media literacy in the social media age

If the US wants to protect young people from misinformation and foreign influence, focusing on TikTok…

From sumptuous engravings to stick-figure sketches, Passover Haggadahs − and their art − have been e

A scholar highlights some of the most interesting versions of the Passover text and how they’ve met…

Are tomorrow’s engineers ready to face AI’s ethical challenges?

Ethics is often neglected in engineering education, two researchers write, despite mounting questions…