Students should learn about impeachment in school – here's how to make it work

Teachers grappling with how to teach current events at divisive times should emphasize history, study original sources and address polarization.

When Congress weighs whether to impeach the president, it is a question of national urgency.

Teachers can help their students understand the impeachment hearings by cultivating the skills required to consider the evidence. They can also help young Americans understand why people see this process in different ways – often based on their political views. Many teachers do this by devoting some time every week to helping students make sense of what is happening.

I’ve been either teaching social studies or researching civics education for the past 25 years. Based on this experience, I have three suggestions for teachers who are grappling with the challenge and ethics of bringing politics into the classroom at this divisive moment in the nation’s history.

1. Emphasize history

It makes sense to start by brushing up on what the Founders of the U.S. government intended.

Depending on how old their students are, teachers can start by explaining or reviewing the process of impeachment as described in the Constitution.

They can also study other relevant documents.

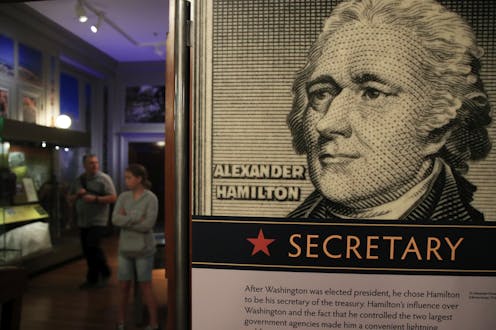

A good one is Federalist No. 65, in which Alexander Hamilton argued that impeachable offenses involve the “abuse or violation of some public trust” and “injuries done immediately to the society itself.” Returning to these documents provides insight into what was meant by “high crimes and misdemeanors.”

Another is Federalist No. 69, in which Hamilton outlined the ways in which the Constitution limits the power of the president. Among these are that a president has term limits, can be impeached and can be tried for crimes once removed from office.

Understanding the purpose of impeachment helps students keep up with the news and consider the charges being brought.

2. Study original sources

Teachers ought to ask their students to read the documents and testimony coming before the public.

To that end, teachers may ask students to read parts of the whistleblower’s account, opening statements of people testifying before congressional committees and show video excerpts from witnesses’ testimony.

Studying these original sources is a civics lesson in and of itself. Students see members of Congress in action, how professionals answer questions and the importance of speaking and writing clearly.

Of course students, like virtually all citizens, can’t make the time to watch all of the proceedings. They must also rely on reporting from news outlets – creating an opportunity to enhance their news literacy.

Teachers can help students become more adept news consumers by watching testimony and then looking at how it is reported by different news sources. Students can then discuss whether the reporting accurately reflects their impressions of what they read and viewed.

3. Address polarization

It may be tempting to think that a teacher could just “stick to the facts” of this impeachment inquiry. But that is not possible or desirable.

Consider the question, “Did Ukraine interfere in the 2016 election?” Is this a credible possibility, as the president contends?

Or is that theory, to use former White House adviser Fiona Hill’s characterization, a “fictional narrative”?

A teacher will have to be ready to a help students sort fact from fiction and identify the political motives behind these views.

The reality is that young people are growing up in a politically polarized country. In my view, if students are going to be prepared for that reality, then educators need to teach about partisanship and ideology.

Though, they may be worried about doing that.

The American Enterprise Institute, a think tank, found in a 2011 survey that Republicans and Democrats have strikingly different views about what should be taught in civics. Republicans are more supportive of emphasizing facts and how the government works. Democrats are more supportive of teaching values like equality and tolerance.

It’s no wonder then, that teachers may be avoiding discussions about impeachment.

They may also fear that they do not have the support of administrators. My coauthors and I found in a report on social studies standards released in 2016 that 43 states expect students to learn about political parties, but only 10 connected that learning to contemporary issues.

The greatest challenge for teachers is that, though impeachment is a question of national urgency, it also aggravates partisan divides. Despite these trends, I have written about and researched with the dean of University of Wisconsin-Madison’s School of Education, Diana Hess how teachers do find ways to engage students in political discussion in ways that their parents and other members of their communities support.

We found that the most successful teachers prepare students with context, evidence and the opportunity to discuss. Young people told us that this approach made them more engaged, more interested in politics and more willing to discuss politics with family and friends.

How widespread is current events instruction?

It’s not possible to know just yet how many students are getting this opportunity to learn about civics and history through the prism of this impeachment inquiry into Donald Trump.

Forty states require high school students to take at least one U.S. history course. And 42 states and Washington D.C. require at least one semester of civics.

Even when not required at the state level, local policies typically require every high school student to take at least one course that includes learning about the Constitution. A study by the Brookings Institution, a think tank, that reviewed 2010 federal data found that 82% of high school students said they had discussed current events at least once or twice a month and 63% said they discussed them at least weekly in class.

My experience shows that teachers often feel like they don’t have enough time to teach their regular curriculum and do justice to current events. Ideally, history and civics teachers can connect the inquiry to other lessons about presidential power, checks and balances or the Cold War.

Still, there are times in which the issues of the day deserve everyone’s attention. Even elementary school students can learn from current events, if adults are willing to take the time to engage them.

[ You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter. ]

Paula McAvoy does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

How a niche Catholic approach to infertility treatment became a new talking point for MAHA conservat

Mainstream medical organizations have criticized ‘restorative reproductive medicine,’ but some Catholics…

How I rehumanize the college classroom for the AI-augmented age

A writer instructor recognizes the role of AI on campus, while elevating social connection and humanity…

Trump administration replaces America 250 quarters honoring abolition and women’s suffrage with Mayf

US coins showcase American identity and public memory through their designs. The America 250 coins just…