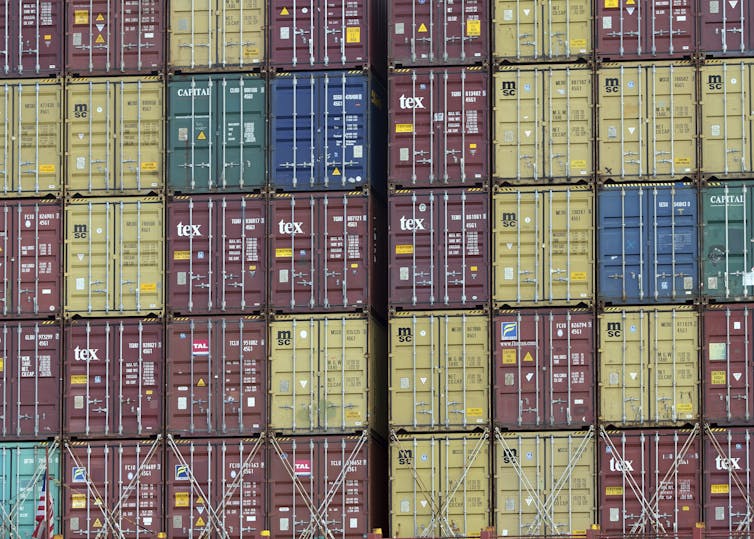

Today's global economy runs on standardized shipping containers, as the Ever Given fiasco illustrate

Before the container was standardized, loading and unloading goods was very labor-intensive, inefficient and costly.

Take a look around you.

Perhaps you’re snacking on a banana, sipping some coffee or sitting in front of your computer and taking a break from work to read this article. Most likely, those goods – as well as your smartphone, refrigerator and virtually every other object in your home – were once loaded onto a large container in another country and traveled thousands of miles via ships crossing the ocean before ultimately arriving at your doorstep.

Today, an estimated 90% of the world’s goods are transported by sea, with 60% of that – including virtually all your imported fruits, gadgets and appliances – packed in large steel containers. The rest is mainly commodities like oil or grains that are poured directly into the hull. In total, about US$14 trillion of the world’s goods spend some time inside a big metal box.

In short, without the standardized container – like the thousands that helped to keep the Ever Given stuck in the mud along the Suez Canal, snarling traffic for almost a week – the global supply chain that society depends upon would not exist. About 30% of global container shipping volumes transit through the Suez Canal.

The Ever Given incident reveals several kinks in the modern supply chain. But, as an expert on the topic, I think it also highlights the importance of the simple yet essential cargo containers that, from a distance, resemble lego blocks floating on the sea.

Trade before the container

Since the dawn of commerce, people have been using boxes, sacks, barrels and containers of varying sizes to transport goods over long distances. Phoenicians in 1600 B.C. Egypt ferried wood, fabrics and glass to Arabia in sacks via camel-driven caravans. And hundreds of years later, the Greeks used ancient storage containers known as amphorae to transport wine, olive oil and grain on triremes that plied the Mediterranean and neighboring seas to other ports in the region.

Even as trade grew more advanced, the process of loading and unloading as goods were transferred from one method of transportation to another remained very labor-intensive, time-consuming and costly, in part because containers came in all shapes and sizes. Containers from a ship being transferred onto a smaller rail car, for example, often had to be opened up and repacked into a boxcar.

Different-sized packages also meant space on a ship could not be effectively utilized and also created weight and balance challenges for a vessel. And goods were more likely to experience damage from handling or theft due to exposure.

A trade revolution

The U.S. military began exploring the use of standardized small containers to more efficiently transport guns, bombs and other materiel to the front lines during World War II.

But it was not until the 1950s that American entrepreneur Malcolm McLean realized that by standardizing the size of the containers being used in global trade, loading and unloading of ships and trains could be at least partially mechanized, thereby making the transfer from one mode of transportation to another seamless. This way products could remain in their containers from the point of manufacture to delivery, resulting in reduced costs in terms of labor and potential damage.

In 1956, McLean created the standard cargo container, which we basically still use today. He originally built it at a length of 33 feet – soon increased to 35 – and eight feet wide and tall.

This dramatically reduced the cost of loading and unloading a ship. In 1956, hand-loading a ship cost $5.86 per ton; the standardized container cut that cost to just 16 cents a ton. It also made it much easier to protect cargo from the elements or pirates, since the container is made of durable steel and remains locked during transport.

The U.S. made great use of this innovation during the Vietnam War to ship supplies to soldiers, who sometimes even used the containers as shelters.

Today, the standard container size is 20 feet long, the same width, but more commonly half a foot taller – a size that’s become known as a “20-foot-equivalent container unit,” or TEU. There are actually a few different “standard” sizes, such as 40 feet long or a little taller, though they all have the same width. One of the key advantages is that whatever size a ship uses, they all, like lego blocks, fit neatly together with virtually no empty spaces.

This innovation made the modern globalized world possible. The quantity of goods carried by containers soared from 102 million metric tons in 1980 to about 1.83 billion metric tons as of 2017. Most of the containerized traffic flows across the Pacific Ocean or between Europe and Asia – usually through the Suez Canal.

Ships get huge

The standardization of container sizes has also led to a surge in ship size. The more containers packed on a ship, the more a shipping company can earn on each journey.

In fact, the average size of a container ship has doubled in the past 20 years alone. The largest ships sailing today are capable of hauling 24,000 containers – that’s a carrying capacity equivalent to how much a freight train 44 miles long could hold. Put another way, a ship named the Globe with a capacity of 19,100 20-foot containers could haul 156 million pairs of shoes, 300 million tablet computers or 900 million cans of baked beans – in case you’re feeling hungry.

The Ever Given has a similar capacity of 20,000 containers, though it was only carrying 18,300 when it got stuck in the Suez Canal.

In terms of cost, imagine this: The typical pre-pandemic price of transporting a 20-foot container from Asia to Europe carrying over 20 tons of cargo was about the same as an economy ticket to fly the same journey.

Cost of success

But the growing size of ships has a cost, as the Ever Given’s predicament showed.

Maritime shipping has grown increasingly important to global supply chains and trade, yet it was rather invisible until the recent logjam and blockage of the Suez Canal. As the Ever Given was traversing the narrow 120-mile canal, fierce wind gusts blew it to the bank, and its 200,000 tons of weight got it stuck in the muck.

About 12% of the world’s global shipping traffic passes through this canal. The blockage had, at one point, at least 369 ships stuck waiting to pass through the canal from either side, costing an estimated $9.6 billion a day. That translates to $400 million an hour, or $6.7 million a minute.

Ship-building companies continue to work on building ever-larger container vessels, and there’s little evidence this trend will stop anytime soon. Some forecast that ships capable of carrying loads 50% times bigger than the Ever Given’s will be plying the open seas by 2030.

In other words, the standardized shipping container remains more popular – and in demand – than ever.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can get our highlights each weekend.]

Anna Nagurney does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

DOJ criminal probe highlights risk of Fed losing independence – a central bank scholar explains what

The investigation follows Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s refusal to toe the White House’s line over interest…

How social media is channeling popular discontent in Iran during ongoing period of domestic unrest

Information is still getting out despite an almost total internet blackout, especially with the help…

What is Christian Reconstructionism − and why it matters in US politics

Christian Reconstructionism, a little-known movement to rebuild society on biblical law, can often shape…