Missy Elliott tours as a headliner − and it’s about time

The six-time platinum-selling artist invites fans into an imagined future that celebrates Blackness and queerness.

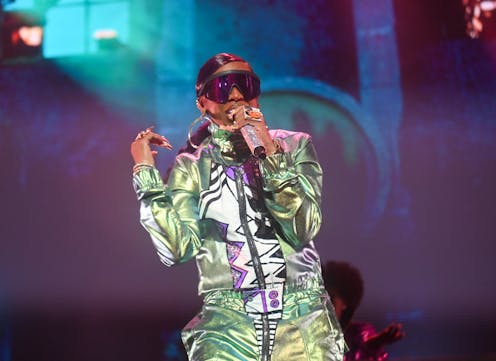

Missy Elliott’s first-ever headline tour, which stops in Philadelphia on Aug. 5, 2024, comes nearly three decades after she released her debut album, “Supa Dupa Fly,” in 1997.

For a seasoned artist like Elliott – a rapper, singer, songwriter and producer whose accomplishments include six platinum-selling albums, four Grammys and an induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame – her first experience as a headliner may seem shockingly overdue.

As a scholar of American studies and Black popular music, I’ve been writing about and discussing Missy Elliott’s artistry for over a decade.

I believe that Elliott’s long wait to headline a tour is in sync with how she’s long refused to be governed by norms of time.

From her “Matrix”-inspired sophomore treatment “Da Real World” to her old-school, hip-hop-influenced album “Under Construction,” Elliott consistently shows that she desires to be – or believes she is – not of this time.

As the name of her tour suggests, she envisions herself “Out of This World.”

‘Funk the clock’

Scholars in Black studies, queer studies and disability studies have explored the role of time in upholding anti-Blackness, homophobia, transphobia and ableism.

They argue that describing America as a post-racial society hinders the fight against racism in the present, that treating queer and trans identities as something new or just a phase leads to LGBTQ+ youth being denied health care, and that championing people who move “past” or progress through their disability ignores systemic barriers.

To push back against such ideas, these scholars explain, Black people “funk the clock” by naming how we still live in the wake or the afterlives of slavery. Similarly, queer and trans people “queer” time by embracing and documenting queer and trans histories. And disabled people “crip” time – to reclaim the pejorative term – by slowing down and caring for their bodies.

Missy Elliott is a Black woman with a disability – she has Graves’ disease and severe anxiety – who breaks cultural norms of gender and sexuality.

Her music often engages time and temporality in ways that align with funking the clock and queering and cripping time. She plays with past and future – treating both as alternative worlds, even utopias, that reject the hostilities of the present.

Supa Dupa Fly futures

On July 12, 2024, Missy Elliott made history as the first Black person, first woman, first American, first rapper and only the second musical act – the Beatles being the first – whose song NASA transmitted to space.

“Missy has a track record of infusing space-centric storytelling and futuristic visuals in her music videos so the opportunity to collaborate on something out of this world is truly fitting,” stated NASA spokesperson Brittany Brown.

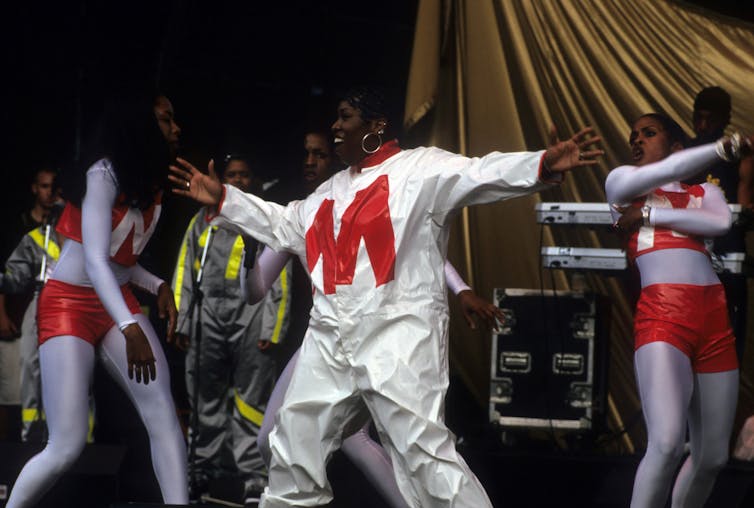

Indeed, the visual aesthetics of Elliott’s first three albums are compelling examples of such futuristic – if not outright Afrofuturist – production. They feature Black cyborgs, space travel and postapocalyptic worlds.

Scholars have demonstrated that Black women’s Afrofuturist music is also often queer, and Elliott’s work is no exception.

Take, for example, her 1997 hit “Sock It 2 Me,” a song about a woman seeking a sexual partner for the night. The woman wants a partner who can “bring the nasty out of me” and allow her to “show you thangs that you can’t believe.”

Importantly, Elliott does not use gendered pronouns in this song. This encourages listeners to imagine the woman’s partner as someone who could be a range of genders and sexualities.

The music video, meanwhile, is set in the future and features Elliott and fellow Black women rappers Lil’ Kim and Da Brat dressed in Mega Man-like outfits. Elliott’s suit eerily anticipates the Gmail logo that premiered years later. The three women ward off an invasion of robots that are attacking a red planet inhabited exclusively by Black women.

Futuristic queerness is also front and center in her 2001 Grammy-winning song “Get Ur Freak On.” The music video is set in a postapocalyptic underground lair in which Black, Asian, queer and disabled people live and dance together intimately.

As I’ve written elsewhere, the song’s use of the term “freak” is telling. “Freak” resonates with how people of color, disabled people and queer people have been seen in U.S. history due to their perceived perversion. And Elliott musically gestures toward these histories by stuttering on the song, using nongendered pronouns and rapping over a beat that mixes Black and Asian sounds.

In so doing, the “Get Ur Freak On” song and video offer an imagined future in which marginalized groups find refuge and solidarity.

Flip it and reverse it

While Elliott’s first three albums explored the future, her most recent three have highlighted the past – most explicitly in sartorial and musical samplings of the 1980s.

Take, for example, her 2002 Grammy hit “Work It.” The song samples 1980s rap groups RUN-D.M.C. and Rock Master Scott & the Dynamic Three. It’s also a highly sexual song in which, among other things, Elliott discusses oral sex, and it famously features her rapping in reverse.

As Black feminist and queer studies scholar Mecca Jamilah Sullivan argues, the song converges “backwards” sexual pleasures and sonic and erotic “reversal.” This, she writes, signals “a broad range of potential erotic differences and sexual deviations that may be viewed as backward or perverse.”

Elliott’s performance on this song is emblematic of what I call the “musical aesthetics of impropriety” – a celebration of sexual desires and practices that defy norms governing Black women’s sexuality.

When Missy Elliott stops in Philadelphia, she will take audiences back in time but also into her vision of the future. And she will do so in service of those who our current society marginalizes due to their race, gender, sexuality or disability.

Fans will be invited to imagine and believe that another world is possible – they just have to change the times.

Elliott H. Powell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Italian teenager Carlo Acutis’ upcoming canonization reflects the Vatican’s desire to appeal to a ne

Italian priest Padre Pio was one of the world’s most prayed-to saints in recent times. As Pio’s…

The real ‘Big Bang’ of country music: How Vernon Dalhart’s 1924 breakthrough recordings launched a g

A musicologist explains how an oft-forgotten opera, pop and jazz singer from New York City launched…

Kamala Harris’ identity as a biracial woman is either a strength or a weakness, depending on whom yo

While many voters embrace Kamala Harris’ candidacy and the fact that she is a multiracial woman without…